The 21st Century path to prosperity––to a broad middle class––is concentrating talent. Not factory jobs. Why? Because today’s mass middle class are professionals and managers who work in offices, schools and hospitals. Not production workers who work in factories.

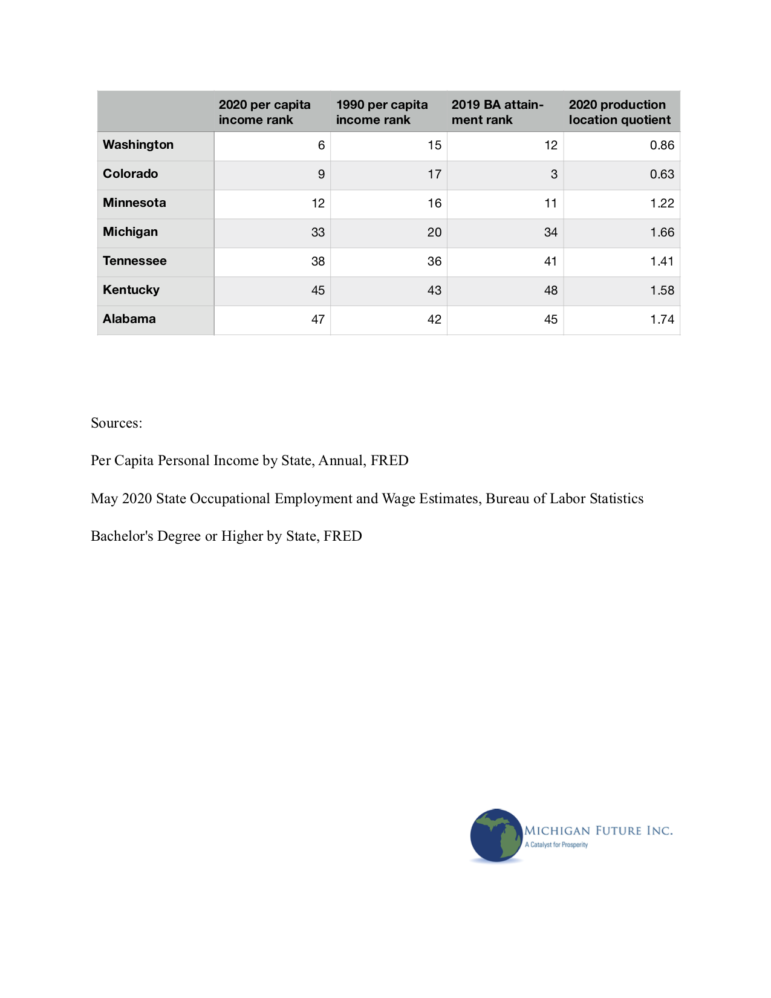

You can see that clearly in the table at the bottom of this post. We compared Michigan to three states with a high proportion of adults with a four-year degree or more (places that are concentrating talent) and three states with a high proportion of production jobs. Minnesota, Colorado and Washington are the three in the first category. Tennessee, Kentucky and Alabama are in the second.

The table looks at each state’s per capita income ranking in 1990 and 2020; their rankings in B.A. attainment in 2019; and their concentration compared to the nation in production (blue collar factory) jobs in 2020.

(Location quotient compares an occupation’s share of state employment with its share of national employment. A location quotient of 2.0 means a state’s employment is twice as concentrated in that occupation as the nation. A location quotient of 0.5 means a state is half as concentrated in that occupation as the nation.)

In 1990 Washington, Colorado, Minnesota and Michigan had nearly identical per capita income rankings. No more. Over the past three decades Washington, Colorado and Minnesota have become more prosperous compared to the nation, while Michigan has fallen from a high-prosperity state to a low-prosperity state.

The common characteristic of Washington, Colorado and Minnesota? A high proportion of adults with a four-year degree or more. This alignment is true across the nation. High per capita income states overwhelmingly are high college attainment states.

What is not a common characteristic of Washington, Colorado and Minnesota? Lots of production jobs. As we explored in our last post, production jobs have been for decades a declining share of employment and now have median wages below the national median. In each state included in the table below, except Kentucky, production jobs have median wages lower than the state median wage.

As Washington, Colorado and Minnesota have gotten more prosperous over the last three decades compared to rest of the country the exact opposite is true for Tennessee, Kentucky and Alabama. In 1990 they were national laggards in per capita income. In 2020 they have fallen even farther behind. And unfortunately Michigan is in the same boat, even more so. Falling from 20th in per capita income in 1990 to 33rd in 2020.

What do Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama and Michigan have in common? Low college attainment and high concentration in production jobs. Yes Tennessee, Kentucky and Alabama have been successful in those three decades in attracting auto plants and auto supplier plants. Most recently Ford’s decision to locate an electric vehicle assemble plant and three battery plants in Tennessee and Kentucky. But that auto factory attraction success has most definitely not been a path to prosperity for Tennessee, Kentucky and Alabama.

As Rick Haglund detailed in a recent article for Crain’s Detroit Business, since General Motors chose Arlington Texas over Willow Run for an assembly plant in 1992, Michigan’s economic development priority has been retaining and attracting motor vehicle factories. It has most definitely not been a path to prosperity for Michigan. Per capita income in 1990 in Michigan was 97% of the nation. In 2020 it is 90%. If Michigan had just stayed at 97% per capita income in Michigan in 2020 would have been higher by $4,400.

While Michigan was declining by more than seven percentage points compared to the nation, Washington––the most prosperous of our talent concentrated states––was growing by 10 percentage points compared to the nation. If Michigan had grown by 10 percentage points since 1990 per capita income in Michigan in 2020 would have been higher by $10,351. To do that Michigan would have to have focused on concentrating talent, rather than competing for factories.

Rather Michigan chose to compete with production jobs concentrated states. Tennessee––the most prosperous of our production jobs concentrated states––had per capita income growth less than one percentage point compared to the nation. It moved from 14 percent below the national average to 13 percent below. Yes it narrowed the gap with Michigan from 11 percentage points to three. But that is almost all because of Michigan’s decline, not Tennessee’s rise.

Post Arlington Michigan has chosen a low-prosperity state economic development strategy. One that might be categorized as chasing factories. To recreate a high-prosperity Michigan, that was the wrong strategy then and is the wrong strategy today.

The path to prosperity for Michigan is having an economy like Washington, Colorado and Minnesota not like that of Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama. And the key to having an economy like Washington, Colorado and Minnesota is concentrating talent. Which means an economic development strategy that makes preparing, retaining and attracting talent––not factories––THE priority.