![]() Last week, the Equality of Opportunity Project, led by Stanford economist Raj Chetty, released another study in their ongoing series on mobility in America. This one was particularly sobering. The headline: black males raised in wealthy households (the top quintile of household incomes), are more likely to be poor as adults than they are to remain wealthy. The odds that a black male raised in a top quintile household would remain in the top quintile as an adult is 17 percent, while there is a 21 percent chance he would fall to the bottom quintile. White males raised in top quintile households have an almost 40 percent chance of remaining there as adults, and even white males who grow up poor, in a bottom quintile household, have a 10 percent chance of making it to the top.

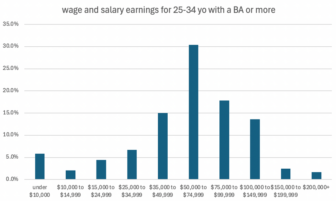

Last week, the Equality of Opportunity Project, led by Stanford economist Raj Chetty, released another study in their ongoing series on mobility in America. This one was particularly sobering. The headline: black males raised in wealthy households (the top quintile of household incomes), are more likely to be poor as adults than they are to remain wealthy. The odds that a black male raised in a top quintile household would remain in the top quintile as an adult is 17 percent, while there is a 21 percent chance he would fall to the bottom quintile. White males raised in top quintile households have an almost 40 percent chance of remaining there as adults, and even white males who grow up poor, in a bottom quintile household, have a 10 percent chance of making it to the top.

The larger story of this research is about the pernicious impacts of racism – both institutional and individual. But this research also sheds light on how many of our current theories for how to reduce racial gaps in economic mobility are inadequate. And how one theory in particular – closing the black-white test score gap – is particularly inadequate.

The new research shows that while black males earn substantially less than white males at every parental household income percentile (the wealth of the family you grew up in), this gap does not exist for women. However, just as it does for men, a large black-white test score gap does exist for women, controlling for family income. So even though throughout their educational lives black females score lower than white females of similar background on achievement tests, this new research finds that there is virtually no difference between black and white females of similar background in high school graduation, just a small gap in college attendance, and no gap in earnings.

As an analysis of the study in the New York Times put it, a likely explanation for why the female black-white test score doesn’t translate to an income gap is that “test scores don’t accurately measure the abilities of black children in the first place.”

While this may seem like a pretty incredible finding, it’s actually just another in a long line of studies that call into question why standardized test scores have become the sole focus of our education system. In the book Crossing the Finish Line, one of the most authoritative studies ever written on college completion, researchers found that a student’s SAT/ACT scores were far less predictive of their eventual college completion than their high school grades. A recent study of the University of California admissions system found that test scores “predict less than 2 percent of the variance in student performance at UC.” And Jay Greene, who heads the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas and sits firmly in the pro-school choice camp – which is typically also pro-test – has written extensively about the number of studies that find that great test score gains don’t predict the outcomes we ultimately care about, like college attendance, college graduation, and later-in-life earnings.

This is really important because when people talk about improving education in Michigan, or becoming a top 10 state in education, or giving all Michigan kids a fair shot, they’re talking about test scores. We want to believe that if we improve test scores and close achievement gaps, that will lead to better life outcomes. All of this research calls this very idea into question.

Again, the larger takeaway from this new mobility research is about reforming a criminal justice system that imprisons far too many black men, and encouraging racial integration in all facets of life through public policy. However, there are lessons for schools in here as well. Throughout the paper, there are graphs showing black males less engaged in school – higher rates of “disruptive” behavior, higher rates of suspension, lower college attendance. But as long as our school system remains hyper-focused on test scores – which turn out to mean much less than we think they do – it will crowd out all of the other things we could be focusing on, which could help engage more students and offer a better shot at success in life. These other things are far less clear than a standardized test score, and have more to do with finding a sense of purpose, belonging, and competence in your educational life than on meeting any threshold on a standardized test.

Designing schools to meet these more nebulous objectives is really hard, but it’s where we should place our focus if we want our schools to have a lead role in providing equal opportunity.