![]() Our latest report provides a set of ideas for how we improve living standards for Michiganders not participating in the high-wage knowledge economy. Last week I wrote about our ideas for providing far more support to jobless individuals, to help them overcome barriers and get on a path towards family-supporting work.

Our latest report provides a set of ideas for how we improve living standards for Michiganders not participating in the high-wage knowledge economy. Last week I wrote about our ideas for providing far more support to jobless individuals, to help them overcome barriers and get on a path towards family-supporting work.

Today’s post details our ideas for making sure that more work in Michigan is, indeed, family-supporting work.

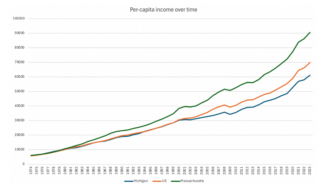

Today, the market is simply not creating enough jobs that pay a family-supporting wage. This is not just a Michigan story, but a national problem, caused by structural changes in our economy. Globalization and automation have put downward pressure on pay for lower-skilled work, and owners of capital and advanced education have captured nearly all the productivity gains since the 1980s.

In this new reality, affluent families are doing well, and non-affluent families – the bottom roughly two-thirds of the income distribution – are less secure. Nationally, median household income has been stagnant as the economy continues to grow. Here in Michigan, household incomes fell for the entire bottom half of the income distribution between the mid 1970s and 2013, while just the top 30% of earners saw meaningful income gains.

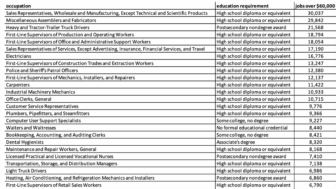

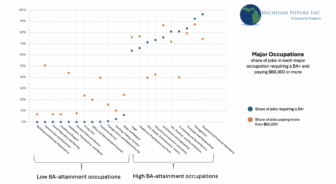

The recently updated ALICE report put out by the Michigan Association of United Ways, finds that 40% of Michigan households are unable to afford basic necessities. Part of the reason is that the majority of available jobs – both today and for the foreseeable future – are not high-wage. The ALICE report notes that 62% of jobs in Michigan pay under $20 an hour, and roughly 40 percent pay under $15 an hour. Job projections through 2024, put out by the Michigan Bureau of Labor Market Information, predict that 30% of annual job openings statewide will be in occupations with a median income under $25,000, and 72% of annual openings will be in occupations with a median under $56,000, the ALICE threshold for a family of four. Almost by definition, the vast majority of jobs will fail to provide a family-supporting wage. Low-wage work is now a structural part of the Michigan economy.

And market forces alone are not going to fix this problem.

Raising wages through public policy levers

However, while wages are unlikely to increase for lower-skilled workers through market mechanisms, there is much we can do to improve the standard of living for non-affluent families through public policy. Below is a menu of ideas – both public investments and employer regulations – that should be on the table if we’re serious about raising living standards for all Michiganders.

Increase the state Earned Income Tax Credit. Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit is an efficient way to help non-affluent workers make up for what they’ve lost over the past 30 years. The EITC, by providing a credit based on wages, serves to both raise wages and incentivize work, and politicians on both sides of the aisle have called for its expansion.

Twenty-six states and Washington, D.C., have a state earned income tax credit to supplement the federal credit, with the state credit pegged to a percentage of the federal credit. In 2012, the state EITC in Michigan was reduced from 20 percent of the federal credit to just 6 percent. Reinstating the EITC to 20% of the federal credit would offer a substantial raise to workers who desperately need it.

Preserve Medicaid. Access to quality and affordable health care is a critical component for households to be able to pay for basic necessities. Michigan has taken a major step in the right direction with its expansion of Medicaid eligibility. That progress should be maintained.

Increase the state/local minimum wage. The current federal minimum wage is historically low, at $7.25 per hour, well below the 1968 peak of $9.54 (in 2014 dollars), and miles below that mark when adjusted for cost of living, productivity gains, and the median wage of the United States worker. There’s been a flurry of minimum wage increases in state and local governments in recent years to make up for federal inaction, based on the principle that an individual should not be able to work a full-time job and still not be able to afford basic necessities. Michigan’s minimum wage is currently above the federal floor, but we should have a serious discussion about the right minimum wage target to help more Michigan families afford basic necessities.

It should be noted that while economic theory tells us a higher minimum wage would lead to fewer jobs, either through company relocation or hiring cuts, a large research base finds employer response to reasonable minimum wage increases to be muted.

Improve collective bargaining rights. The decline in collective bargaining, both in the US and particularly in Michigan, has likely contributed to rising inequality and declining wages for the median earner. Michigan should change course and seek to expand, rather than restrict, collective bargaining rights to improve the standing of Michigan workers.

Paid family leave. To make work pay we also need to ensure individuals don’t lose their jobs in the case of a family medical emergency, or birth of a child. Several states have family and medical leave laws to make up for federal shortcomings in this area. Some pay for leave policies through a state payroll tax, while others require employers to provide paid leave.

Closing pay gaps by race and gender. Making work pay means making sure work pays the same for everyone, regardless of gender or race. Minnesota has an appointed pay equity coordinator to hold local units of government accountable to pay discrepancies, and Massachusetts and California have passed laws barring employers from banning conversations amongst employees about pay, to improve transparency. Measures like these would be a start, but any policy that seeks to increase transparency around who gets paid what for what work would contribute to closing these gaps.

Create stability for hourly workers. Another obstacle in the path of low-wage workers, damaging not only their quality of life but also their odds of holding a job, is irregular work schedules. “Just-in-time” scheduling practices to match the supply of workers as closely as possible to demand from customers prevents workers from attaining a dependable income stream and creates unavoidable family-work conflicts. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors adopted a Retail Workers Bill of Rights requiring employers to provide more advance notice for changing work schedules, offer priority access to additional work hours to current employees, and pay workers who did not receive sufficient notice of reduced hours or are forced to wait “on-call.”

Increasing the standard of living for all Michiganders

Both now, and for the foreseeable future, the jobs available to the majority of Michiganders will not be high-paying. The question is how do we use public policy to help improve the standard of living for these individuals, when their standard of living is unlikely to be improved by market forces alone? In the report, we offer some of our ideas. We’re sure there are others, we’re eager to learn more, and we hope you’ll join us in this conversation for how we improve the standard of living for all Michiganders.