Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This is the thirteenth post in the series. See links to previous posts below:

Post #1: Educational attainment and economic development

Post #2: Educational attainment and economic well-being

Post #3: College completion rates

Post #4: Beyond free college

Post #5: Developing writers in K-12

Post #6: Building college-ready skills in K-12

Post #7: An assessment system designed for college success

Post #8: Holding school systems accountable to postsecondary success

Post #9: BA attainment and K-12 funding

Post #10: Improving completion rates at four-year colleges

Post #11: Public policy levers to boost completion rates at four-year colleges

Post #12: Improving completion rates at Michigan’s community colleges

In my last post, I outlined a set of reforms community colleges could take on to improve completion rates and transfer pathways. In this post, I’ll look more specifically at the public policy levers that can encourage institutions to take on these reforms.

Provide the resources necessary for redesign

As I wrote in my previous post, the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) intervention at the City University of New York (CUNY) colleges was remarkably successful, doubling three-year completion rates for developmental education students. But this kind of intervention does not come cheap. Participating students received tuition waivers; free books and transit; and comprehensive and mandatory counseling supports. This last piece was particularly critical, and, presumably, expensive. While a typical community college advisor faces caseloads of roughly 1,200 students, and the typical community college student visits with their advisor just once per semester (if at all), the ASAP program ensured counselors had caseloads of between 60 and 80 students, and students were required to visit with their advisors twice per month. This means that for ASAP to be as effective as it was, CUNY needed to hire a lot of advisors.

For Michigan colleges to replicate the kind of success CUNY experienced through the ASAP program, far more resources, beyond the status quo, will be required. In a previous post, I reviewed research showing the impact that additional grant funding has on the quality of a student’s education at four-year institutions – how lower-selectivity four-year institutions, when provided additional funding, tend to put it towards student support services, as they seek to replicate the experience students have at elite institutions. This same kind of student success grant funding scheme could be applied to Michigan’s community colleges as well, where community colleges are awarded funds specifically designated for colleges to implement the successful features of the ASAP program. Last year the state rolled out a competitive grant program that seeks to support Michigan community colleges in taking on ambitious student success reforms.

Invest in high quality data systems

Just as we highlighted in the four-year space, we think there is great potential to use broadly accessible, user-friendly data to spur reform at the community college level. The most commonly cited student success metric for community colleges is the share of first-time, full-time students who complete a credential within 150 percent of the time allotted (e.g., completing a two-year associate degree in three years of initial enrollment). Community college leaders, however, may argue that this figure offers a poor representation of whether or not a school is doing right by their students. They’ll note that most community college students are not full-time, but part-time students, balancing work and school; that students come to community college for all sorts of reasons that may not result in the completion of a credential; and that these completion rates do a poor job of capturing transfer outcomes.

Setting aside for a moment the veracity of these claims, the bigger question is why we don’t have data systems that capture, with great detail, this broader set of outcomes. If there is a particular community college that is sending large numbers of their students to four-year institutions, and those students are experiencing success, state policymakers and education leaders should know that, so we can learn from successful institutions and spread promising practices to less successful ones. The opposite is also true – if we find that a particular community college is transferring very few students, and/or the students who transfer are not experiencing success at their destination college, we can figure out ways to better support reforms at the sending institution.

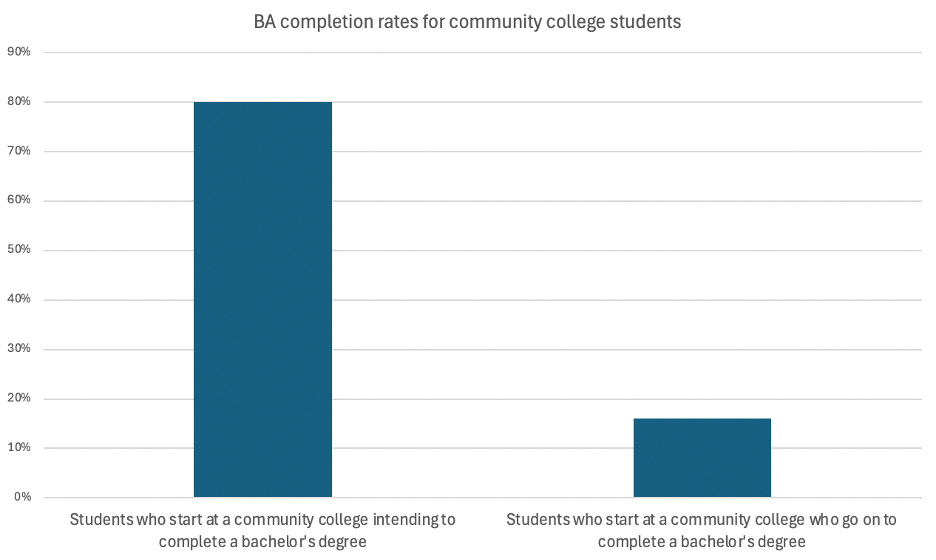

We should know this data by race/ethnicity, age, and income, and it should be widely available and easily accessible. Indeed, as low as completion rates are for community college students overall, the numbers are that much worse for low-income students and students of color. Here in Michigan, only five percent of Black students who begin at a community college will complete a bachelor’s degree six years later, and just ten percent of low-income students will. This kind of fine-grained data is only available through a report by the Community College Research Center, but the state could and should put it at everyone’s fingertips.

More and better data is also needed on labor market outcomes for all community college students, both those who do and don’t complete a credential. If those who leave community college prior to completing a credential are still capturing some amount of economic value from their community college experience, we should know that. However, it is unlikely this is the case. Research finds that though the labor market returns on sub-BA credentials are modest, those who complete a credential do much better than those who take some number of credits but fall short of the credential.

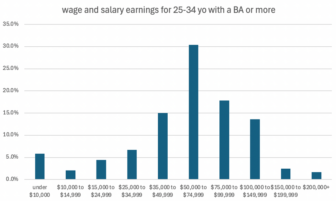

More data is also needed on the returns to various credentials. Though labor market returns by major and degree do vary at the baccalaureate level, we also know that the wage premium for a bachelor’s degree holder is large, regardless of major. The same is not true at the sub-BA level. Yes, there are some credentials that yield a solid earnings premium; but there are others that provide no boost, or whose holders do worse, relative to those with just a high school diploma. Prospective students deserve to know this data for the schools and programs they are considering, and colleges themselves should look closely at this data, to make student-centered choices about what programs to keep, and which to jettison.