Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This is the sixth post in the series. In this post, I explore how the K-12 system would need to change to ensure more students are prepared to pursue and attain a four-year degree. See links to previous posts below:

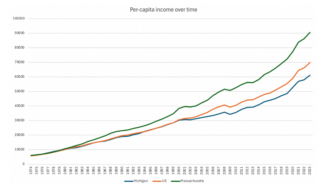

Post #1: Educational attainment and economic development

Post #2: Educational attainment and economic well-being

Post #3: College completion rates

Post #4: Beyond free college

Post #5: Developing writers in K-12

In my last post, I wrote about what is perhaps the most important skill required for college and increasingly career success – the ability to write (and therefore think) critically, analytically, and clearly. And how this skill is rarely prioritized in our K-12 education system.

In this post I’m going to go through the range of other kinds of knowledge, behaviors, mindsets, and skills needed for college success that also sit at the periphery of our K-12 system. Most of these capacities could best be summarized as those that are needed for a student to learn independently – an essential skill for college and career success.

David Conley, an emeritus professor of education at the University of Oregon, has developed what is likely the most comprehensive model of college readiness. It consists of a whole range of knowledge, skills, mindsets, and behaviors that you will not find assessed on any standardized test. Under Conley’s model, for a student to make a successful transition to college she must possess:

(1) Key cognitive strategies, that enable her to learn content from a range of disciplines. These strategies include the ability to formulate problems, engage in active inquiry, construct arguments, and interpret conflicting claims to arrive at a truth.

(2) Core academic subject knowledge and skills, which include the central ideas and concepts that construct various disciplines; reading comprehension and writing fluency; a deep conceptual understanding of basic mathematics, and algebra in particular; a fluency in scientific thinking; and the ability to evaluate evidence and understand broad themes and big ideas in the social sciences.

(3) Academic behaviors, which include the ability to assess one’s own understanding of a set of material, as well as the study and organizational skills to manage one’s own time and mastery over a given set of material.

(4) Contextual skills and awareness, which includes understanding all of the often unwritten rules of the college application and selection process, as well as a whole range of knowledge and skills that enable one’s success in college, including how to interact with faculty, administrators, and peers; how to take advantage of student support systems; and how to work collaboratively with peers.

Research suggests most of these strategies, knowledge, skills, and behaviors are not actively being developed in the typical American high school. Rather, school is school. There is content to be learned, and students will be tested on this content, both in class, and through college entrance exams. Learning tasks are largely shallow in nature, involving the copying down and memorizing of material. Compliance is rewarded. Little attention is paid to constructing quality arguments; understanding central ideas and concepts that form the foundation of various disciplines; achieving a transferable fluency in core academic courses; creating an environment in which students manage their own learning; creating an environment in which students pursue knowledge for its own sake; or teaching the unwritten rules that govern admission to and success in college.

In the book In Search of Deeper Learning, Harvard education scholars Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine define “deeper learning” as learning in which a student builds a deep understanding of the concepts that make up the domains they are studying, and that asks them to not only consume but produce knowledge. This definition of deeper learning, and the kind of pedagogy required to achieve it, aligns closely with the development of the kinds of knowledge, skills, mindsets, and behaviors Conley believes are needed for success in college. But what Mehta and Fine discover is that educational models designed for deeper learning are largely missing in American public high schools.

Where they did find models of deeper learning, they found them not in the typical classes of the typical public school, but in “affluent private schools and in the highest-track classes at the most advantaged public schools,” as well as in elective courses and extracurricular activities – spaces where teachers perhaps felt freer to go deeper into a particular subject and engage in more discussion with students.

It’s probably no coincidence that in all these environments – private college-prep schools or elective and extracurricular courses in traditional public schools – instructors are for the most part free from the strictures of standardized tests and mandated curricula. Though standardized tests give us some valuable information about what a student does or does not know, or what they can or cannot do, we argue that the way in which our education system is oriented around standardized tests detracts from our ability to adequately prepare them to be successful in college.

In my next post I’ll further explore the ways in which our current assessment systems are often at odds with the development of college ready skills, and what kinds of assessments ought to replace them if we are to build towards a K-12 system that produces many more students prepared for college and career success.