Last year, the state budget included funding for a program called the Michigan Talent Partnership. The program is based on a proposal we put forth, centered on creating more dense, walkable, and vibrant neighborhoods in Michigan cities, capable of retaining and attracting highly-educated young talent.

One way this program is different from many other grant programs focused on cities and local communities is that the MTP is focused on economic development, rather than community development. In today’s economy, economic growth is driven by highly-educated, highly-mobile young talent, who tend to locate in dense, walkable, and vibrant neighborhoods in the central cities of major metropolitan areas. So to drive economic development in Michigan, we need to be laser-focused on creating more talent magnet neighborhoods that can attract young talent, at scale, from anywhere in the world. In today’s economy talent attracts capital and quality of place attracts talent.

Therefore, our intention with this program was always to target neighborhoods of relative strength. This program was not intended to achieve traditional community development goals, such as revitalizing distressed neighborhoods, as important as those programs are. Rather, the goal of the MTP is to invest in neighborhoods that already have some semblance of density, walkability, and vibrancy, but need more investment if they are to attract talent at scale. And, indeed, no matter how dense, walkable, or vibrant your favorite neighborhood is in your favorite Michigan city, it is a long way off from the scale of density, walkability, and vibrancy needed to attract talent, at scale, from anywhere in the world.

To better illustrate this gap we are going to look at what are often considered the most vibrant neighborhoods in Detroit and Grand Rapids – Midtown in Detroit and the neighborhoods east of downtown along Wealthy Street in Grand Rapids – against Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood. For this exercise, in order to compare geographies of equal size, we’re defining Midtown fairly broadly, as the area between the Lodge (west) and 75 (east) and 94 (north) and 75 (south); the area between the Lodge (west) and Woodward (east) and Euclid (north) and 94 (south), to include Tech Town and a portion of the Virginia Park neighborhood; and the Woodbridge neighborhood just west of Wayne State (map below). For Grand Rapids, the geography is roughly bounded by Fulton (north) and Hall (south) and Plymouth (east) and Division (west), encompassing the Eastown, East Hills, Baxter, and Midtown neighborhoods (map below). Lakeview is defined as the area between Ravenswood (west) and Lake Michigan (east) and Montrose (north) and Diversey (south), minus the Buena Park neighborhood in the northeast of that geography (map below).

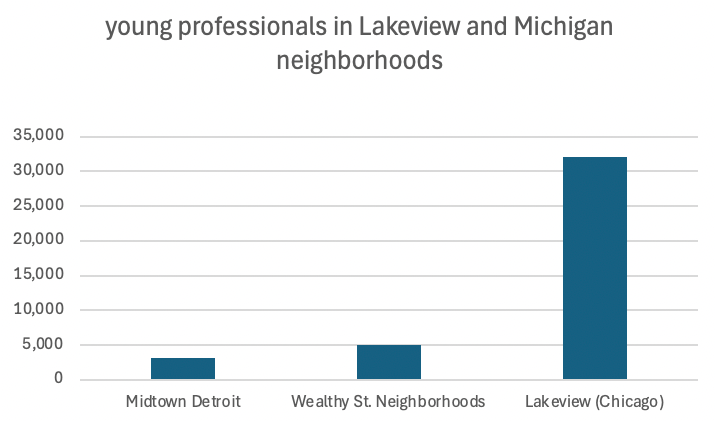

Young professionals in Lakeview and Michigan’s top neighborhoods

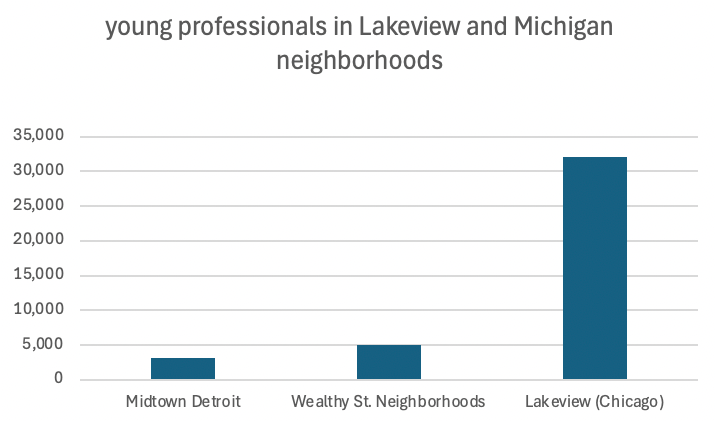

Let’s start with the headline figure: the number of young professionals (25-34-year-olds with a bachelor’s degree) that live in each neighborhood. As of 2023, there was an estimated 3,100 young professionals living in this Midtown geography, an area of roughly 3.4 square miles. There were nearly 5,000 young professionals living in the Wealthy Street neighborhoods, an area of 3.24 square miles. In Lakeview, an area of roughly 3.1 square miles, there are just over 32,000 young professionals.

This, in a nutshell, is the gap. Lakeview has nearly 29,000 more young professionals (in a slightly smaller geography) than what is considered Detroit’s most dense, walkable, and vibrant neighborhood, and 27,000 more young professionals than the young-talent center of Grand Rapids. In fact, the Lakeview neighborhood has 7,000 more young professionals than the entire city of Detroit, and 10,000 more young professionals than the entire city of Grand Rapids.

Understanding the scale of this gap is important. The instinct for many state and local officials is often not to prioritize a city’s relatively vibrant neighborhoods for further investment because they are thought to be “done”; folks are already investing there and moving there, so we can place our focus on other parts of the city. But if we’re thinking from an economic development lens, and trying to create talent magnet neighborhoods that truly can attract young talent from anywhere in the world, Midtown and the Wealthy St. neighborhoods are anything but done. Rather, they would be perfect candidates for a program like the MTP – places where city officials could build on the area’s strengths through walkable urban design, arts and cultural offerings, outdoor recreational, and the expansion of amenities.

Amenities, amenities, amenities

Indeed, an analysis of amenities available in these neighborhoods offers another salient data point. Amenities can be defined as anything that enhances the convenience or enjoyment of a place, and could range from grocery stores to schools to parks. But for young professionals, the amenities that often matter most are restaurants, coffee shops, and bars. And here, the difference between Michigan’s vibrant neighborhoods and Lakeview is again stark.

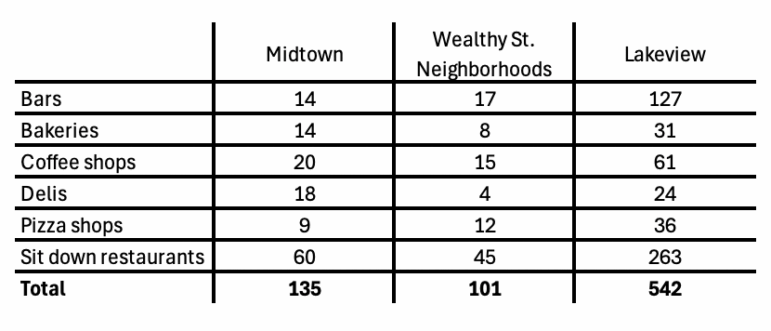

In Midtown, as of 2021, there were 14 bars, 14 bakeries, 20 coffee shops, and 60 sit down restaurants (the data for this analysis comes from a U-M census tract level study of eating and drinking establishments).[i] If we include delis and pizza shops, it brings the total to 129 eating and drinking establishments, or roughly 41 per square mile.

In the Wealthy Street neighborhoods, there are 17 bars, 8 bakeries, 15 coffee shops, 4 delis, 12 pizza shops, and 45 sit down restaurants, for a total of 101 establishments, or 31 per square mile.

This might feel like a lot. But it’s nowhere near the density needed to create a talent magnet neighborhood.

Lakeview, by contrast, is littered with amenities. The neighborhood has 127 bars, 31 bakeries, 61 coffee shops, 24 delis, 36 pizza shops, and 263 sit down restaurants. In total there are 542 eating and drinking establishments in Lakeview, or roughly 173 per square mile, more than four times the level of density we see in Midtown and more than five and a half times the level of density we see in the Wealthy St. neighborhoods.

If you’ve ever walked these neighborhoods, you understand this data intuitively. For example, in Midtown, despite its growth in recent years, you can still walk for long stretches without bumping into another bar, restaurant, or coffee shop. Some areas of the geography still feel quite desolate. The same is not true in Lakeview. You are simply surrounded by amenities. And, therefore, the neighborhood is that much more walkable, that much more vibrant.

A potential critique of this analysis might be that the populations of Midtown or the Wealthy St. neighborhoods simply can’t support the level of amenities we see in Lakeview. Indeed, the population of Lakeview (103,000) is five times that of Midtown (20,300) and three and a half times that of the Wealthy St. neighborhoods (28,000). However, this begs a classic question of which comes first – the growth of population or the growth of amenities. Said differently, does population growth drive the growth of amenities, or do new amenities attract population?

Of course, it likely works both ways. But one would have to assume that at least at the outset it’s a neighborhood’s commercial development, it’s amenities, that make it an attractive place for young folks to land. In 1989 the sociologist Ray Oldenburg wrote a book called The Great Good Place, celebrating the importance of what he called “third places” to urban vitality. A third place is a place that is not your home nor your place of work, but a place of leisure, that you can gather with friends or just sit by yourself, with a book and a coffee or a beer. It is often these places that are what’s attractive about a neighborhood – a favorite bar, a favorite coffee shop, new restaurants to try.

If this is correct – that it’s the amenities that come first in creating talent-magnet neighborhoods – one could argue that there is a role for public policy in generating a high density of amenities in potential talent-magnet neighborhoods as a first order priority, particularly before population levels in a neighborhood reach a point at which neighborhood businesses can be self-sustaining.

Other features of talent magnet neighborhoods

So, one defining feature of a talent magnet neighborhood is that it is covered with amenities that matter to young talent, like bars, bakeries, coffee shops, and restaurants. What are the other characteristics of a place like Lakeview, and how do these characteristics differ from the kinds of things we generally focus on in conversations around population attraction?

First, it’s heavy on young adults, but light on school age kids. Nearly half (47%) of the neighborhood’s residents are between 20 and 34, compared to 27% for Chicago as a whole. And only 7% of Lakeview residents are between the ages of 5 and 19, versus 17% for the city as a whole. This is important to note because when we talk about talent attraction, the first thing people will often raise is the quality of the schools. “How can we attract population if we don’t have good schools?” people will ask. But while good schools are of course important for a whole number of reasons, they are not important in creating talent-magnet neighborhoods, because, as the data suggest, many families move out of talent magnet neighborhoods when their children reach school age. This may not be desirable, and is something to work towards changing, but the fact of the matter is that the quality of the schools in Lakeview were not what turned the neighborhood into a talent magnet – the young adults populating Lakeview are not there for the schools.

Other characteristics of Lakeview: the neighborhood has remarkably high levels of educational attainment – 83.4% of the neighborhood’s residents have a BA or more; 63% of households are renter households; nearly half of the housing stock is in buildings with 20 or more units; forty percent of households don’t own a car; and 37% of those who commute to work do so by public transit.

This again bucks up against many common views about what attracts people to a place. In discussions around population attraction in Michigan, the low cost of housing is often billed as a feature of the state. But the young talent headed to Lakeview aren’t worried about owning their own home – they are going to rent. And their neighborhood is so walkable, and so connected with public transit, that they don’t need a car.

The description of this neighborhood, and the people within it, match directly to the experience of my peers after graduation from college and then graduate school. I was one of the few that did not locate in a dense neighborhood of a major city (I taught middle school on the Texas-Mexico border after college, and moved to Detroit shortly after graduate school). But nearly everyone else did. New York, DC, Chicago. They all rented, they didn’t own a car, they used public transit, and they were surrounded by bars, bakeries, coffee shops, and restaurants.

If Detroit, and Michigan as a whole, is going to create more talent magnet neighborhoods, we need to begin with an understanding of just how far even our most dense, walkable, and vibrant neighborhoods are from being the kind of place that can attract talent at scale. From an economic development perspective, we need to make strategic investments in Michigan neighborhoods that are already relatively dense, walkable, and vibrant, and enhance those features so that these places are competitive for talent on a national scale.

[i] Esposito, Michael, Li, Mao, Finlay, Jessica, Gomez-Lopez, Iris, Khan, Anam, Clarke, Philippa, and Chenoweth, Megan. National Neighborhood Data Archive (NaNDA): Eating and Drinking Places by Census Tract, United States, 2003-2017. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2020-09-16. https://doi.org/10.3886/E115404V2