Over the past several weeks, I wrote a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This is the fourteenth and final post in the series. See links to previous posts below:

Post #1: Educational attainment and economic development

Post #2: Educational attainment and economic well-being

Post #3: College completion rates

Post #4: Beyond free college

Post #5: Developing writers in K-12

Post #6: Building college-ready skills in K-12

Post #7: An assessment system designed for college success

Post #8: Holding school systems accountable to postsecondary success

Post #9: BA attainment and K-12 funding

Post #10: Improving completion rates at four-year colleges

Post #11: Public policy levers to boost completion rates at four-year colleges

Post #12: Improving completion rates at Michigan’s community colleges

Post #13: Policy levers to improve outcomes at Michigan’s community colleges

We are often surprised that we still have to make the case – to policymakers, business leaders, and parents alike – that the best thing a young person today can do to lay a strong foundation for a successful forty-year career is to pursue and complete a four-year college degree. Likewise, when we are confronted with data showing unmistakable link between the educational attainment in a given state and that state’s overall prosperity, we are surprised that we still have to make the case that the best thing a state can do to grow its economy is ensure many more of their young people go on to pursue and complete a four-year degree.

But in this concluding post I’m going to stay focused on the individual, and summarize the key themes I’ve been writing about in the previous thirteen posts: about the impact a four-year college degree can have on one’s life outcomes, and the need for Michigan to design its education systems to ensure every young Michigander is prepared to pursue and complete a four-year college degree.

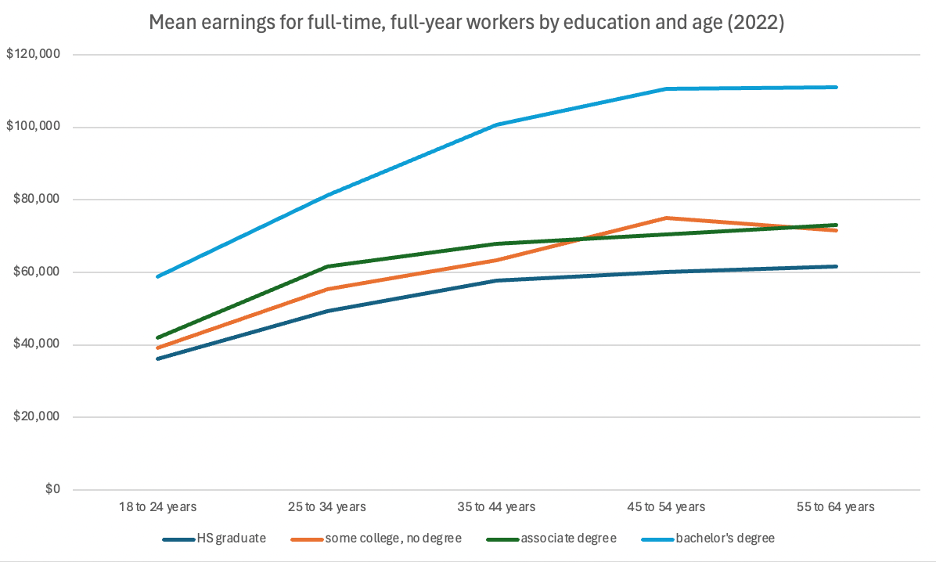

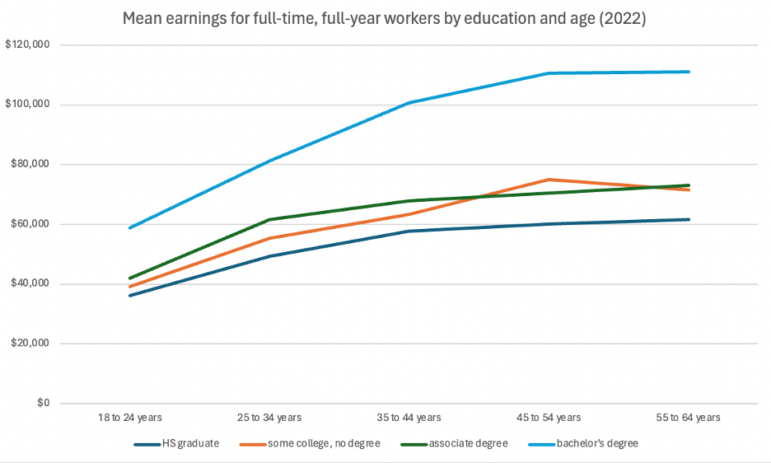

Let’s again review the data, which are unimpeachable. The “wage premium” associated with earning a four-year college degree is large and growing. If we look at the average full-year, full-time worker with a bachelor’s degree (this analysis is limited to bachelor’s degree holders, and does not include those with graduate degrees, whose earnings are even higher), we find that in 2022 that worker earned roughly $96,500. This is $42,000 more than the average income for a full-year, full-time worker with no education beyond high school, $33,000 more than a worker with some college, but no degree, and $29,800 more than a worker with an associate degree. The gap was slightly smaller, though still substantial, for workers early in their careers ($22,700, $19,700, and $17,030 respectively), but is massive by mid/late career: for those between 55 and 59, the gaps were $52,900, $41,200, and $38,900 (see Chart below).

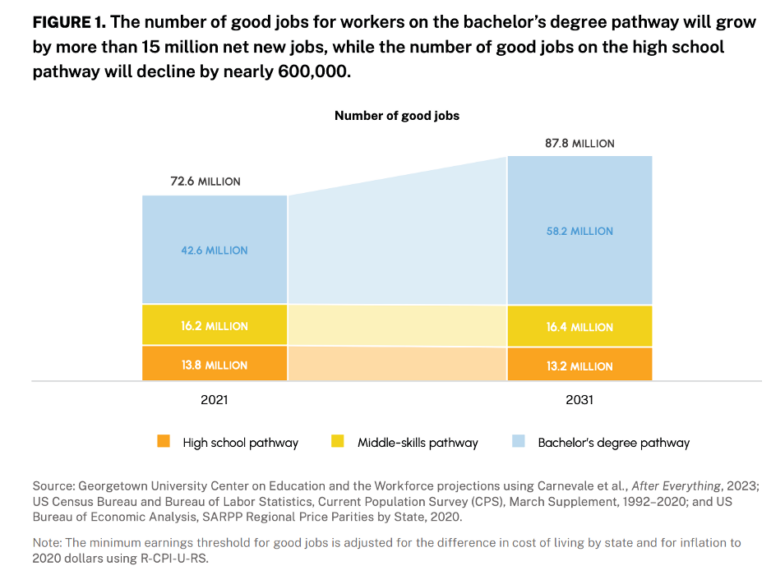

But maybe this is backward looking, one might argue. Some claim that a four-year degree may still provide an earnings bump today, but will not in the years ahead. Wrong again. According to a new report from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, in 2021 there were nearly 73 million “good” jobs, defined as those that pay a median of $74,000 to workers ages 25-44, and $91,000 to workers ages 45-64. Nearly 43 million of those jobs (roughly 60%), require a four-year degree. These researchers project that by 2031, the number of good jobs will grow to nearly 88 million, and roughly 58 million (roughly 66%) of those jobs will require a four-year degree. Only 200,000 good jobs requiring a sub-BA credential will be added over that time period, and the number of good jobs requiring no education beyond high school will decline by 600,000. Meanwhile, the number of good jobs requiring a four-year degree will grow by 15.6 million. This means that of the good jobs added to the economy between 2021 and 2031, nearly all will require a four-year degree.

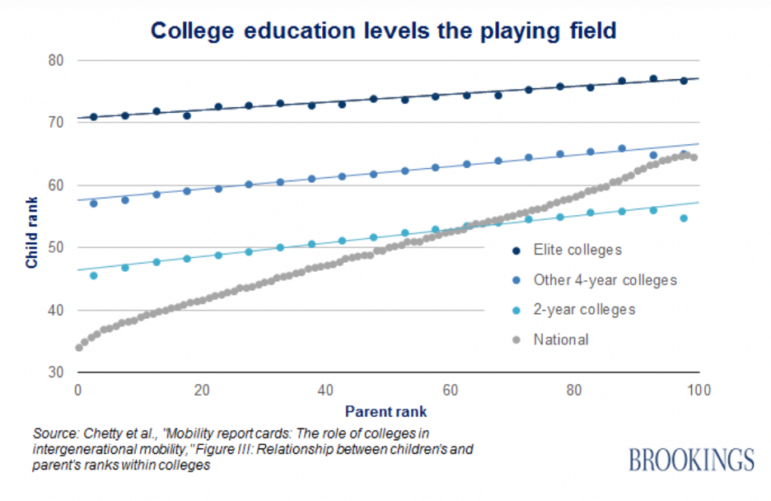

Pursing and completing a four-year degree is also the most dependable route towards economic mobility in our society today. Below is a great chart from a Brookings analysis of Opportunity Insights data, a massive data set that charts economic outcomes across generations. What they found was that, in general, a parent’s income rank was highly correlated with their child’s income rank; in other words, if a child grew up poor, they were likely to remain poor as adults. Unless they got a four-year degree. A child who grew up in the poorest fifth of households but earned a four-year degree was, on average, vaulted to the top half of earners as an adult. If that child found their way to an elite college, they jumped to the top third of earners.

But beyond any chart or graph I can show you, we should be preparing all young people in Michigan to pursue and complete a four-year degree because to do otherwise would be to close off opportunity to some segment of the population. Preparing students to attend and succeed at a four-year college education represents our best chance to ensure all young people are equipped with a broad-based education that enables them to pursue a range of potential careers, the landscape of which will inevitably shift over the next fifty years, just as it has in the previous fifty.

Writers and thinkers who care about racial and socioeconomic equality have long understood the necessity of a broad-based education, equating it not only with improved economic prospects, but with a sense of power and agency in one’s life. The famed sociologist and civil rights icon W.E.B. DuBois, writing in the early to mid 20th century, when the modern “knowledge” economy was still more than half a century away, advocated fiercely for a broad-based, liberal education for all, because he knew that advanced education equaled opportunity. University of Wisconsin education professor Matthew Hora writes, “For W.E.B. DuBois, the freedom to pursue a liberal education was essential for racial equality, ensuring that African Americans had as many opportunities to become doctors, politicians, scientists, and lawyers as whites did. But DuBois was not arguing for the creation of a class of black elites. For him, a liberal education was the key to a liberated mind and to men and women who knew ‘whither civilization is tending and what it means.'”

The data-driven case for pursuing and completing a four-year college degree is rock solid. Pursing a four-year degree is worth it, and then some. But you also don’t need any charts or graphs to tell you that. Education has always been the gateway to agency and opportunity, and it still is today. And we owe it to young Michiganders to provide them with an education that enables them to pursue any opportunity they set their hearts to.

So that’s the case. That is why we believe we need an education system that is set up to prepare all young Michiganders to pursue and complete a four-year college degree. The previous thirteen posts I wrote for this series provide some ideas for how we can go about doing that, though its only a start, and, as always, much of the real work is in the details. But we would love your thoughts, and we hope some of these ideas can serve as a starting point from which we can build a world-class K-16 education system here in Michigan.