Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This is the ninth post in the series. See links to previous posts below:

Post #1: Educational attainment and economic development

Post #2: Educational attainment and economic well-being

Post #3: College completion rates

Post #4: Beyond free college

Post #5: Developing writers in K-12

Post #6: Building college-ready skills in K-12

Post #7: An assessment system designed for college success

Post #8: Holding school systems accountable to postsecondary success

In my last post, I noted that one way to hold schools accountable to building the skills needed for postsecondary success is to actually hold them accountable for their students’ postsecondary success. A system that pushed schools to regularly reflect on their students’ postsecondary outcomes would compel those schools and school systems to identify the features of their educational model that did or did not support postsecondary success.

As I noted in my last post, one piece of that model that would become glaringly apparent to most schools if they were forced to go through this exercise would be the inadequacy of their college counseling services. The quality of college counseling a student experiences is incredibly important to their eventual college success, yet most schools are woefully understaffed, and therefore unable to provide high quality college counseling services that can mean the difference between college success or dropping out.

The lack of high-quality college counseling in most schools is a problem that can only be solved by more resources. To hire more high-quality college counselors, schools need more money.

Improving college counseling services is just one of the many ways that additional funding for K-12 schools can help to improve postsecondary outcomes. There are many others. From smaller class sizes to increased special education supports to implementing college prep curriculums like Advanced Placement (AP) and International Baccalaureate (IB), any reform that might have a shot at improving postsecondary outcomes will require K-12 funding above and beyond the status quo.

In this post, I will briefly review the evidence around K-12 funding and postsecondary outcomes, and discuss why expanding educational attainment cannot be done on the cheap.

K-12 funding and reform

It’s hard to talk about K-12 education reform without also talking about funding. Any meaningful reform one might advocate for – higher teacher pay, smaller class sizes, additional help for special education students, curricular reforms, revamped teacher training, expanded college counseling – would require funding beyond the status quo. This is particularly true in schools and districts serving non-affluent students. For all the faults and potential areas for improvement in our K-12 system, those schools and districts serving affluent students generally do a decent job of preparing them for success in college and beyond. To be sure, some of the advantages these students have come from what they experience outside of school. But schools – and the resources that enable them to attract and retain experienced, high-quality teachers, fully staff their special education departments, and offer a wide array of extracurricular and elective courses – also play a role. If we are going to ask those schools serving non-affluent students to prepare a far larger share of their students for college success than currently meet that threshold, we need to equip them with the needed resources as well.

Over the past decade, a strong consensus has emerged in the literature that school funding is really important to student achievement and educational attainment – and that it’s that much more important for non-affluent students. In a landmark study by C. Kirabo Jackson and colleagues, the authors look at school spending “shocks” over a period of several decades brought on by legislative action or court orders. And they find that if a non-affluent student attends a school that receives a 20% increase in funding, and that increase persists through twelve years of education, that student is likely to complete an additional year of education, earn 25% more as an adult, and is 20% less likely to be low-income as an adult. In the world of education research, these are huge impacts. Meanwhile, more affluent students who experienced the same funding shocks saw no change in their predicted attainment or economic outcomes. In short, adequate funding really matters, and it really matters specifically for non-affluent students.

What does adequate mean? Bruce Baker, a school finance expert at Rutgers University, and his colleagues publish an annual report looking at education funding adequacy across U.S. states. While there is tremendous variation between states (roughly half of all states continue to grant less revenue per pupil to their higher-poverty districts than to their lower poverty districts), on average higher-poverty districts are funded at roughly 20% higher levels than lower-poverty districts. However, when Baker and colleagues model the level of funding needed for students in higher-poverty districts to achieve average educational outcomes (as measured by test scores of basic math and reading skills), they find that students in higher-poverty districts should be funded at rates nearly 90% higher than lower-poverty districts.

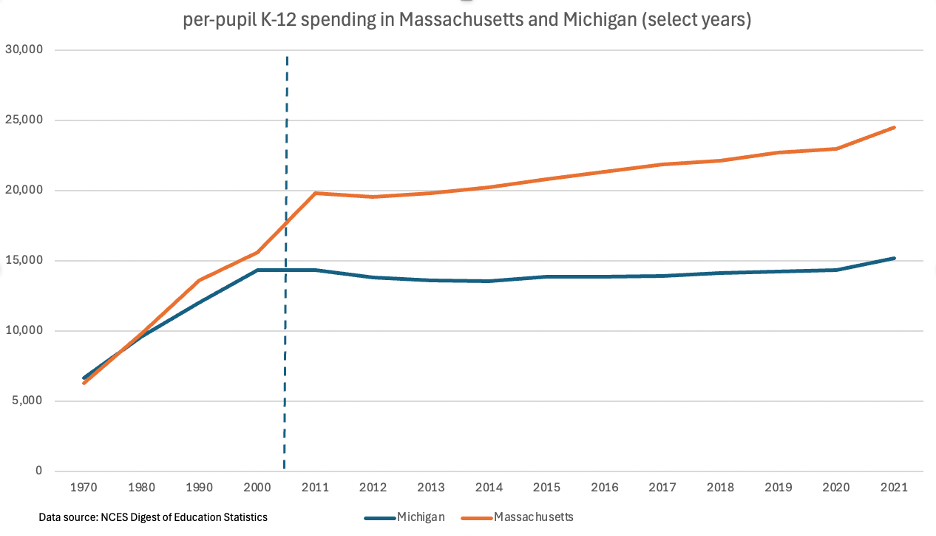

Here in Michigan, we fall far short of this adequacy target. Baker and his colleagues find that Michigan’s highest poverty school districts receive 53% less funding than would be required to achieve average outcomes. And 41% of Michigan students reside in districts that are funded at below adequate levels (it’s worth noting that in high-scoring Massachusetts, just 25% of students are in districts with below adequate funding, and the highest poverty districts are only 10% below the adequacy target. The chart at the top of this post shows the large gap in per-pupil spending between Michigan and Massachusetts).

If we are going to hold schools accountable to the postsecondary outcomes of their students (and we should), ask them to provide high-quality college counseling services, and ask them to ensure all their students leave high school as analytical writers, with a deep understanding of core academic content, and a set of competencies that enable them to learn independently, we need to give them the resources to do it. States need to ensure that their schools and districts serving non-affluent students are funded at levels far higher than what is allocated for schools and districts serving affluent students if we are to get anywhere close to our goal of increasing educational attainment for all students.

In my next post we will leave the confines of the K-12 system, and begin to look at the reforms needed in our four-year and community college systems if we are to dramatically increase educational attainment here in Michigan.