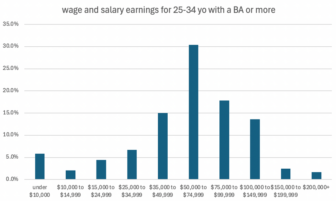

Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This is the twelfth post in the series. See links to previous posts below:

Post #1: Educational attainment and economic development

Post #2: Educational attainment and economic well-being

Post #3: College completion rates

Post #4: Beyond free college

Post #5: Developing writers in K-12

Post #6: Building college-ready skills in K-12

Post #7: An assessment system designed for college success

Post #8: Holding school systems accountable to postsecondary success

Post #9: BA attainment and K-12 funding

Post #10: Improving completion rates at four-year colleges

Post #11: Public policy levers to boost completion rates at four-year colleges

My last two posts looked at strategies four-year colleges can deploy to increase completion rates at their institutions, and public policy levers the state can deploy to encourage institutions to take on these strategies.

In my next two posts I’ll be looking at the community college system, and the institutional strategies and public policy levers that can improve completion rates and transfer pathways at Michigan’s community colleges.

Success rates at community colleges are not great. Completion rates at two-year colleges, both nationally and in Michigan, are quite low: nationally, just 38% of full-time students complete a credential within six years of first entering the institution, and here in Michigan completion rates are below that national figure at 26 of our 28 community colleges.

But what about transfers? One important role of the community college system is to serve as an entry-point to the broader higher education system; students can start at a community college before transferring to a four-year institution. Indeed, 80 percent of students who start at a community college say they intend to transfer to a four-year school. However, despite these high expectations, just 16 percent of students who start at a community college will have earned a bachelor’s degree six years later.

In this post I’ll look at strategies to improve completion rates at two-year colleges, and strengthen transfer pathways.

Redesigning community colleges

The potential areas for reform in the community college landscape are too many to be named here, but we can outline broad themes that community colleges ought to pursue, and that state policies ought to incentivize. These broad themes are largely pulled from Redesigning America’s Community Colleges, the definitive text on community college reform, written by Thomas Bailey, Shanna Smith Jaggars, and Davis Jenkins of the Community College Research Center at Columbia University.

Bailey and his colleagues write that what is needed at the community college level is not reforms at the edges, but a complete redesign of the system. At base, the community college system was simply not designed for the aims we currently need it to achieve – namely, to take a student population that is less academically prepared and more likely to face barriers outside the classroom than the general college-going population, and then ensure they experience success. As the authors write, “the same features that have enabled these institutions to provide broad access to college make them poorly designed to facilitate completion of high-quality college programs.”

Here I will highlight five core areas for reform that community colleges need to take on in order to dramatically increase student success rates:

- Move from a “cafeteria style” model to structured pathways. Traditionally, community colleges have been designed to offer something for everyone, allowing students to select the courses or programs that are right for them. However, entering community college students are often ill-equipped to select the right courses or structure the right pathways, leading to false starts and eventual drop out. Leading community colleges have instead sought to dramatically limit student choice, by instituting guided pathways, default curriculums, and meta-majors, whereby students select a general area of interest, and are then assigned a pre-determined pathway or basket of courses.

- Intentional design around course scheduling. Temporal flexibility is another hallmark of the community college experience, as students take courses that fit around their schedule – after work, at night, or on weekends. However, this type of flexibility also contributes to students’ failure to make meaningful progress, and to eventually dropping out. The programs with the highest completion rates are often those that provide options for full-time enrollment and block scheduling.

- Supplemental instruction and co-requisite coursework. For years, entering community college students have been hampered by remedial education: courses designed to build foundation skills, but which carry no credits towards graduation, and in which students often struggle. To counter this, leading schools have introduced “co-requisite” models, in which students are placed directly in a credit-bearing course while simultaneously taking a course that offers supplemental instruction, allowing students to build foundation skills while making progress towards graduation.

- Expanding the number of academic advisors, and instituting mandatory advising. In 2007, the City University of New York (CUNY) launched the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), which doubled completion rates for participating students. The ASAP program introduced a number of popular reforms, including mandatory full-time enrollment, block scheduling, structured pathways, and financial assistance for books and transportation. But perhaps the most powerful intervention took place around the structure of academic advising. Traditionally, advisors at community colleges have enormous caseloads, with some as high as 1,200 students per advisor – in the ASAP program, advisors had a caseload of between 60 and 80 students. And whereas the average community college student might meet with an academic advisor once a semester or academic year – if at all – ASAP students are required to meet with their advisors twice a month, and attend any tutoring or other support sessions that might be prescribed following those meetings. The ASAP structure is much closer to the kind of academic advising one would see at elite four-year universities with high graduation rates. It only follows that the student body entering community colleges, who are less academically prepared and face more out-of-class barriers than their peers attending prestigious four-year colleges, would need advising services on par with if not more intensive than those offered at elite institutions.

- Reforming community college instruction to center on more active forms of learning. Research on college success finds that if there is a single factor most important to student success it is, perhaps obvious enough, student engagement. If a student is interested in and motivated to learn the content before them, they are that much more likely to take on the academic behaviors needed to be successful. And Bailey notes that if there is a single pedagogical shift community college instructors can make to boost engagement in their classrooms, it is a shift from a “transmission” style of delivery (i.e., lecture-style instruction, presenting content to be learned) to a “learning facilitation” style of teaching, where a professor guides students through problems as students construct knowledge and understanding on their own. In recognition of the need for pedagogy centered on active learning and engagement, Valencia College, for years a leader in community college success efforts, shifted how they award tenure based on faculty achieving pedagogical goals that they set out for themselves through individual learning plans.

Improving transfer outcomes

As previously noted, though the vast majority of entering community college students plan to one day transfer to and graduate from a four-year college, less than one in five actually do. So what can we do to ensure more students achieve the goal they set out for themselves when they first step foot on a community college campus?

There are good examples across the country of strong partnerships between individual institutions, in which a particular community college and a particular four-year college work together to establish transfer pathways for their students, ensuring the transferability of credits and instituting advising supports to ensure a smooth transition. And, indeed, partnerships like this should be highlighted, and encouraged.

But the real work to be done is at the system level to ensure students entering any community college have a decent shot at obtaining a bachelor’s degree from any four-year college they might transfer to. A major priority in this area is establishing articulation and transfer agreements between all two-year and four-year institutions in Michigan. This is obviously easier said than done. Four-year institutions, particularly elite four-year institutions, may be likely to guard against policies that push for transfer uniformity, the logic being that part of what makes the institution elite is the non-transferability of the educational experience at that institution.

However, many states have done this hard work of executing universal articulation agreements. Thirty-eight states have policies in place that require a set of core lower-division courses be transferable; thirty-five states guarantee the transfer of an associate degree, such that associate degree holders will be able to transfer all of their credits at a public four-year institution, and enter as a junior; and thirty-one states have taken the additional step of instituting common course numbering between community colleges and four-year institutions. Michigan, at last check, had taken on none of these popular reforms.

In my next post, I’ll outline some state policy levers Michigan can deploy to encourage Michigan institutions to take on these potentially impactful reforms that can help turn Michigan community colleges into engines of opportunity and social mobility.