Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This is the eleventh post in the series. See links to previous posts below:

Post #1: Educational attainment and economic development

Post #2: Educational attainment and economic well-being

Post #3: College completion rates

Post #4: Beyond free college

Post #5: Developing writers in K-12

Post #6: Building college-ready skills in K-12

Post #7: An assessment system designed for college success

Post #8: Holding school systems accountable to postsecondary success

Post #9: BA attainment and K-12 funding

Post #10: Improving completion rates at four-year colleges

In my last post I wrote about the need for Michigan’s four-year institutions to improve completion rates. What is the role of state policies in encouraging and supporting our four-year institutions to do that?

The answer is not immediately obvious. The knee-jerk reaction that we have seen in states across the country is to try to increase completion rates through “performance-based” funding schemes, where state funding is allocated to institutions based on, for instance, completion rates or workforce outcomes. However, research has shown that these policies can skew institutional behavior in undesirable ways. For instance, in an effort to boost graduation rates schools could end up restricting access to lower income or less academically prepared students who might be less likely to graduate. In addition, such schemes, almost by definition, can end up penalizing those institutions most in need of support, which is not a good long-term strategy for creating a statewide system that increases the number of students completing bachelor’s degrees.

So, if not performance-based funding, what is the right lever to increase completion rates? In this post I’ll outline two core strategies we can deploy: one that is relatively cheap though perhaps not a very strong lever, and one that is likely a stronger lever, but is much more expensive.

Strategy 1: Shine a light on student success data

One relatively low-cost way the state can compel institutions to boost completion rates is by publishing student success data in a way that’s publicly accessible and user-friendly. Currently, this data is hard to access. The federal Department of Education maintains the National Center for Education Statistics, and through their “College Navigator” tool users can uncover a range of data about every institution, including financial aid, net price, admissions data, and completion rates. However, the site is not user friendly, nor widely known. One can imagine the state putting together a user-centered site that highlights completion rates, by racial and income subgroups, over time, to see how an institution is or is not improving.

There is some evidence that this strategy can compel institutions to improve. In 2011, Wayne State University had a six-year graduation rate of just 26%, and just 7.6% for Black students. A number of organizations and the press began to highlight this data publicly, and called on Wayne State to take on the hard work of ensuring more of their students left with a degree. And this public pressure did indeed spark institutional change. By following the playbook popularized by Georgia State, Wayne State earned national awards for its rapid improvements in student success. In 2023, the institution’s six-year graduation rate was 60%, more than double what it was in 2011, and its six-year graduation rate for Black students had risen to 40% – still a lot of room to grow, but moving in the right direction.

Strategy 2: Provide funding for institutions to implement the student success playbook

Aside from the pressure of public data, Michigan can also boost completion rates by ensuring our four-year schools have the resources needed to take on impactful student success reforms. David Deming, a Harvard University economist, has found that “there is a strong causal relationship between per student spending by an institution and degree completion.” “More spending” might not feel very innovative, but it turns out to be essential if we hope to boost completion rates.

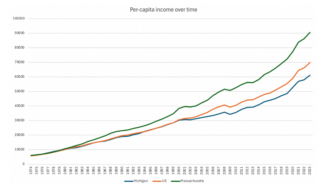

Deming notes that between 1990 and 2015, inflation-adjusted state spending on higher education rose less than 4 percent, while college enrollment grew by 45 percent. This means that our public colleges have, over the past three decades, been asked to support many more students with less resources. Deming notes that colleges have always spent much more per student than they charge in tuition; the more they are able to spend per student, on academic support, instruction, and advising, for instance, the higher quality the student’s educational experience. Deming refers to this surplus that colleges spend above and beyond the price of tuition as the “subsidy.” Deming notes that in 1990, as a result of more generous public support for higher education, public institutions had, on average, $7.26 in subsidy for every one dollar paid in tuition; by 2014, this subsidy had been nearly cut in half, down to $3.87. While elite institutions can lean on high tuition rates and large endowments to provide financial, academic, and social supports, Deming notes that minimally selective public institutions, which end up serving the majority of students, “often have large classes and provide little in the way of academic counseling, mentoring, and other student supports” because of budgetary constraints. When colleges are able to boost spending on student supports and mentoring, however, we see increases in persistence and completion rates.

The common critique of simply increasing spending on higher education is that the institutions will not use the additional funding wisely. Indeed, it’s not hard to find an op-ed suggesting that our nation’s colleges are simply funneling student tuition into fancy gyms and dining halls, all to lure more students paying higher tuition. Though this narrative is not entirely baseless (institutions have increased spending on facilities to compete for students), a hard look at the data yields a more complicated picture. For example, spending on deferred maintenance from an initial building boom in the 1960s has driven facilities spending far more than new buildings. Still, if there is concern that institutions receiving additional state funding will spend the money not on student supports but on fancy buildings, the state could restrict how the funds could be used, requiring some share be put towards counseling, academic advising, instruction, and academic supports.

However, even these restrictions might be unnecessary. Research has shown that when higher education institutions are provided additional public resources, they generally put the money towards student supports, as they try and emulate the kind of educational experience found at highly-selective institutions. Completion rates are higher at highly-selective institutions in part because they admit students who are better prepared academically, but also because they have far more resources than their less selective peers. With these additional resources, students are provided robust wraparound supports that, in effect, don’t allow them to fail. Less selective institutions, when provided additional resources, attempt to provide these same supports. Deming found that “a 10 percent increase in state funding of nonselective public institutions leads to a 17 percent increase in spending on academic support programs.”

It turns out that if we care about completion rates, state spending on higher education – that is, funding to support the institutions themselves – ends up being really important – even more important than financial aid programs. For all the attention on financial aid to individual students – be it federal Pell grants, state-based “free college” programs, or even more ambitious efforts like the Kalamazoo Promise – there is very little evidence to show these programs meaningfully impact completion rates. The removal or easing of the burden of tuition is surely a positive intervention and could both increase access and allow students to take on behaviors that would increase the odds of persistence and completion. However, if a student needs additional supports – if they’re struggling in their coursework, or they don’t know what classes to take, or they feel like they don’t belong in college – tuition assistance is of no help. Rather, the student needs support from the university; they need a higher quality education.

In my next post I’ll begin exploring the reforms needed in Michigan’s community college system if we are to ensure the roughly 15,000 Michigan high school graduates that enter a community college every year are entering a system that will expand, rather than restrict, the opportunities available to them.