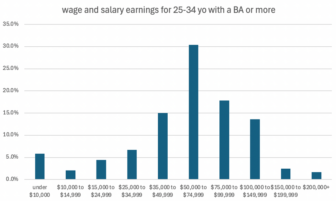

Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This is the tenth post in the series. See links to previous posts below:

Post #1: Educational attainment and economic development

Post #2: Educational attainment and economic well-being

Post #3: College completion rates

Post #4: Beyond free college

Post #5: Developing writers in K-12

Post #6: Building college-ready skills in K-12

Post #7: An assessment system designed for college success

Post #8: Holding school systems accountable to postsecondary success

Post #9: BA attainment and K-12 funding

In the past several posts I’ve looked at our K-12 system: the competencies the K-12 system needs to build in its students for them to be successful in college, the accountability system needed to push the K-12 system to build those competencies, and the funding required to enable all schools to build these competencies.

We will now turn our attention to the higher education system. And because here in Michigan the four-year college system is a completely different animal from the two-year college system, with completely different opportunities for reform, we will look at these systems separately, starting with the four-year system. And we’ll start with a hard look at how four-year colleges – both nationally and here in Michigan – are doing at getting the students who enter their institutions to graduate with a bachelor’s degree (some of this data was reviewed in a previous post, but this post takes a deeper look at the figures).

The state of college completion at four-year colleges

Let’s say, for a moment, that we were to design a K-12 system as I have described in my previous posts: one that prioritizes the development of the knowledge, skills, behaviors, and mindsets student needed to succeed in college and career; one that teaches students how to think critically, communicate clearly, and learn deeply; and one that prioritizes the transition from K-12 to higher education.

Even if this were to happen, we would still need to redesign our systems of higher education, to ensure that far more of the students who attend college end up leaving with a degree in hand.

There were roughly 3 million 16- to 24-year-olds who completed high school in 2015. Roughly 2 million (69% of all graduates) went on to college, with 1.3 million attending a four-year college, and 700,000 attending a two-year college (these figures are taken from Table 302.10 in the NCES Digest for Education Statistics). Of those that went directly to a four-year college, roughly 850,000 (65%) graduated with a four-year degree within six years of entry. Of those that started at a two-year college, 238,000 (34%) received an associate degree within three years, and roughly 112,000 (16%) went on to receive a bachelor’s degree within six years of entry. In total, on top of the roughly 1 million high school graduates from the 2015 cohort who did not enroll in any college at all, this leaves another at least 800,000 students who began college, but had no two- or four-year degree to show for it six years later (It should also be noted that this paints a relatively rosy scenario, because it assumes that all those who entered college were attending full-time, and that the group who graduated with a two-year degree is mutually exclusive from those who started at a two-year college and eventually earned a bachelor’s degree).

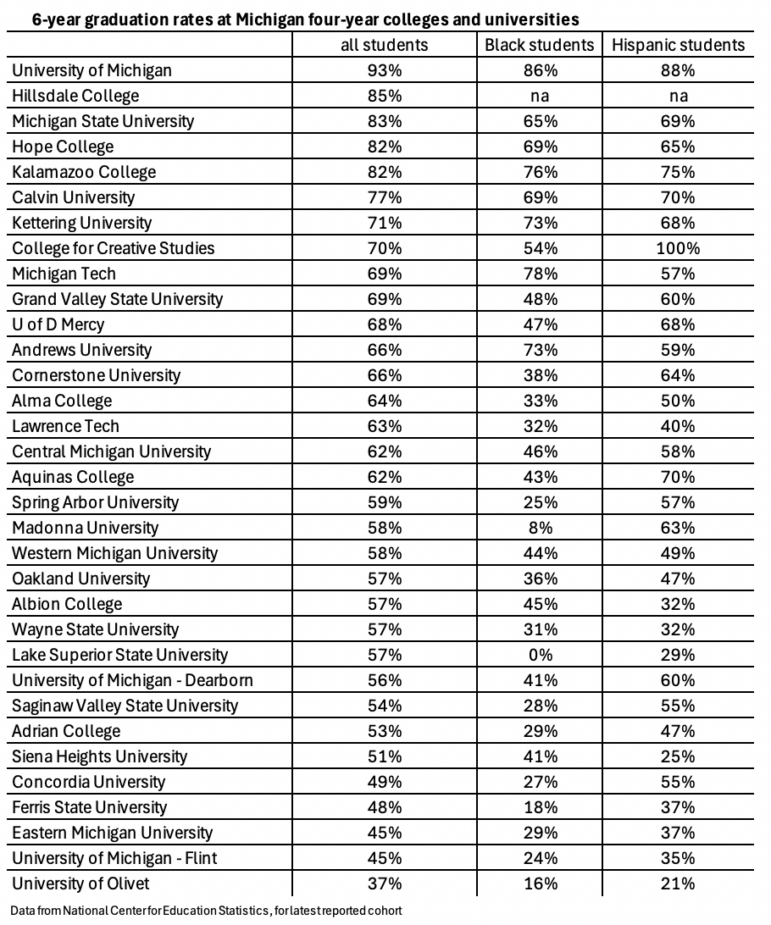

Here in Michigan, our bachelor’s degree granting institutions vary dramatically in the share of entering students who leave with a degree six years later. The University of Michigan and Michigan State University graduate 93% and 83% of their students, respectively, while Ferris State University and Eastern Michigan University graduate just 48% and 45% of their students, respectively. The performance of each institution rests on many factors, including a school’s financial resources (U-M’s endowment is nearly $18 billion and MSU’s is $4 billion; EMU and Ferris State have endowments closer to $100 million) and the academic qualifications of entering students. Still, of the 33 bachelor’s degree granting institutions I looked at (full table copied below), 20 have six-year graduation rates below 65%, 23 have six-year graduation rates for Black students below 50%, and 12 have six-year graduation rates for Hispanic students below 50%. These figures are clearly a cause for concern, and require action.

The good news is that we know what it takes for colleges to graduate many more students than they currently do. Over the past two decades, a number of pioneering institutions have written the guidebook on what it takes to dramatically improve graduation rates, particularly for non-affluent and first-generation students.

Georgia State University in Atlanta is considered by many to be the standard bearer for student success. Georgia State is a mid-selectivity public institution that in the early 2000s graduated just 30% of its students. Since then, however, led by former president Mark Becker and former senior vice president for student success Tim Renick, the school transformed itself into a leader in student success, boosting its graduation rate by nearly 70 percent between 2003 and 2017, and eliminating outcome gaps between white and Black students. They did it through a number of now well-known strategies, including:

- Obsessive attention to data on student success, using predictive analytics to better understand which students were likely to struggle when, and developing new programs to intervene at those pain points.

- Dramatically increasing student support staff, and, with the support of robust data systems, reaching out to students proactively, rather than waiting for students to come to them.

- Implementing an emergency cash grant program to provide students who are on track academically but short on tuition with small grants to make up the difference and keep them enrolled.

More important than any one strategy, however, was the way in which university leadership prioritized student success as a central attribute of the institution. Georgia State leadership made the conscious decision that they weren’t going to try and become an elite public institution, but rather one that admitted and then graduated academically marginal non-affluent students. This commitment, more than anything else, seems to be what’s most needed for institutions to make progress on student success.

(However, it should also be noted that despite Georgia State’s improvements, graduation rates at the institution have plateaued over the past several years, stuck at just over 50 percent for both all students and for Black students.)

In my next post, I’ll dive into some public policy levers we can deploy to encourage Michigan’s four year institutions to take on the hard work of increasing completion rates at their institutions, and provide them the support needed to do so.