A statewide survey conducted by the Detroit Regional Chamber earlier this year reported some startling data about Michiganders’ views on the value of a four-year college degree. As reported in the survey, just 26.5% of Michigan voters said a college education was “very important” to landing a successful job in Michigan, while just 27.5% said a four-year degree was worth the money.

For those interested in the long-term well-being of young Michiganders – and the long-term financial health of our state – these figures should be alarming. Today’s labor market is functionally bifurcated: there is one labor market for those with a four-year degree, and one for those without. And there is a gulf of opportunity between these two markets.

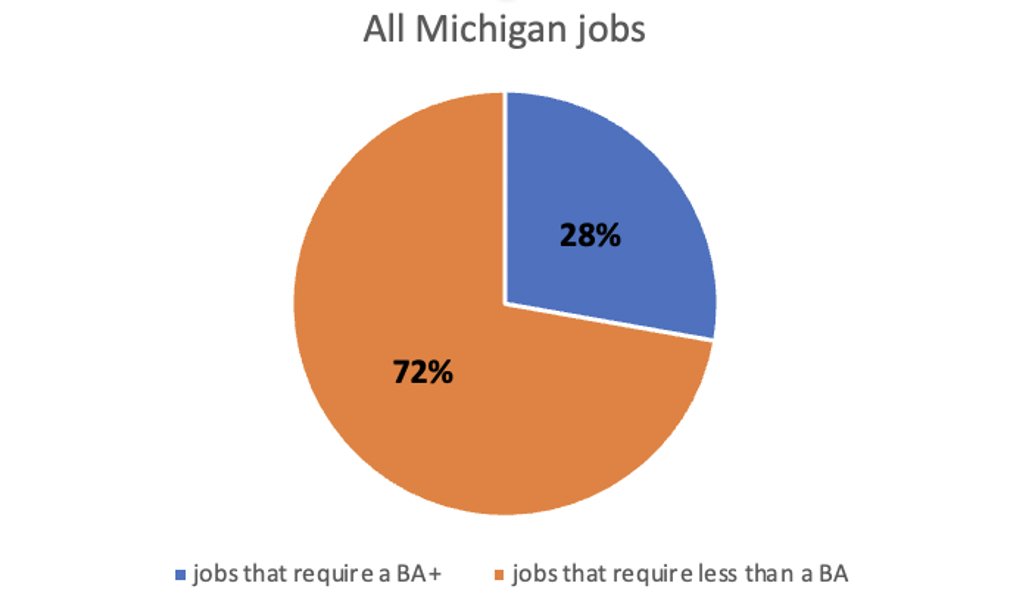

There are roughly 4.2 million payroll jobs in Michigan today (all data for this analysis comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics wage and occupation data for Michigan). It is true that the vast majority of these jobs – roughly 72%, or just over 3 million jobs – do not require a four-year degree. In fact, 62% of these jobs (2.6 million) require no education beyond a high school diploma. So, strictly speaking, a four-year college degree is not necessary to find job in today’s economy.

The question, however, is whether a four-year degree is necessary to find a good job in today’s economy.

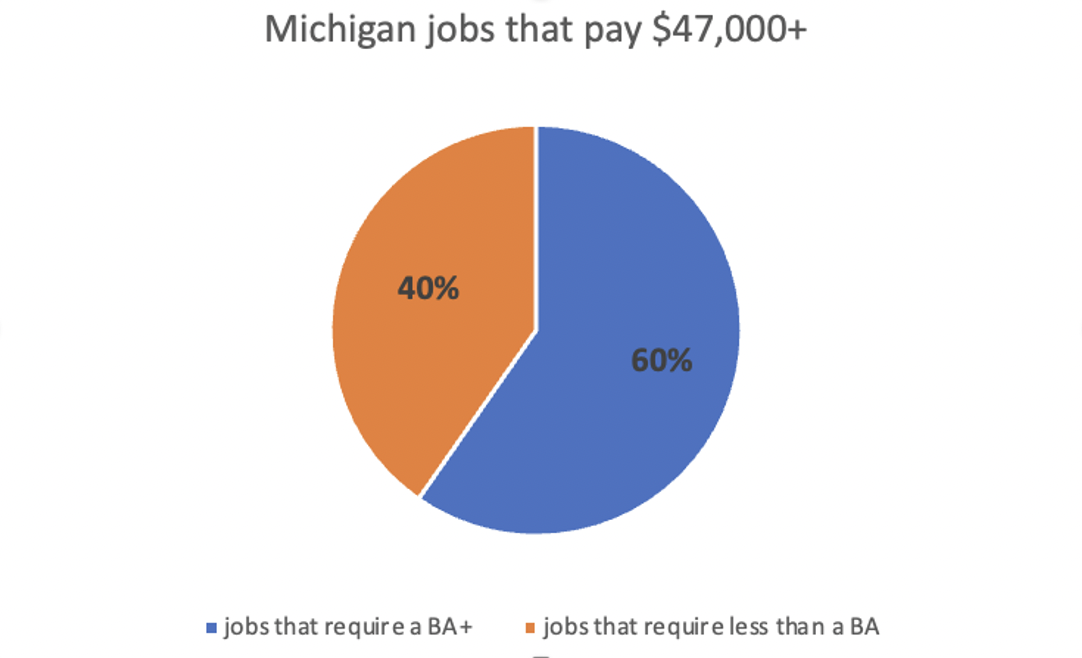

If we define a good job as one that pays at least $47,000 (our definition of “low middle-class”), that 4.2 million job figure is more than cut in half, down to just 1.9 million jobs (in defining pay, I am taking the median annual income for each occupation). For these jobs, the above chart is flipped, where now the majority of jobs do require a BA – roughly 60% of jobs that pay at least $47,000 (1.1 million jobs), require a bachelor’s degree or more.

However, a single earner household with a couple of kids earning $47,000 would likely still face significant challenges in making ends meet. $47,000 is well below the United Way’s ALICE threshold – defining what Michigan households need to pay for the essentials – which they peg at around $60,000 for a household with two kids. So, what if we define a good job as one that pays at least $70,000 per year, our definition of upper middle class? How does that change the market for available jobs based on education?

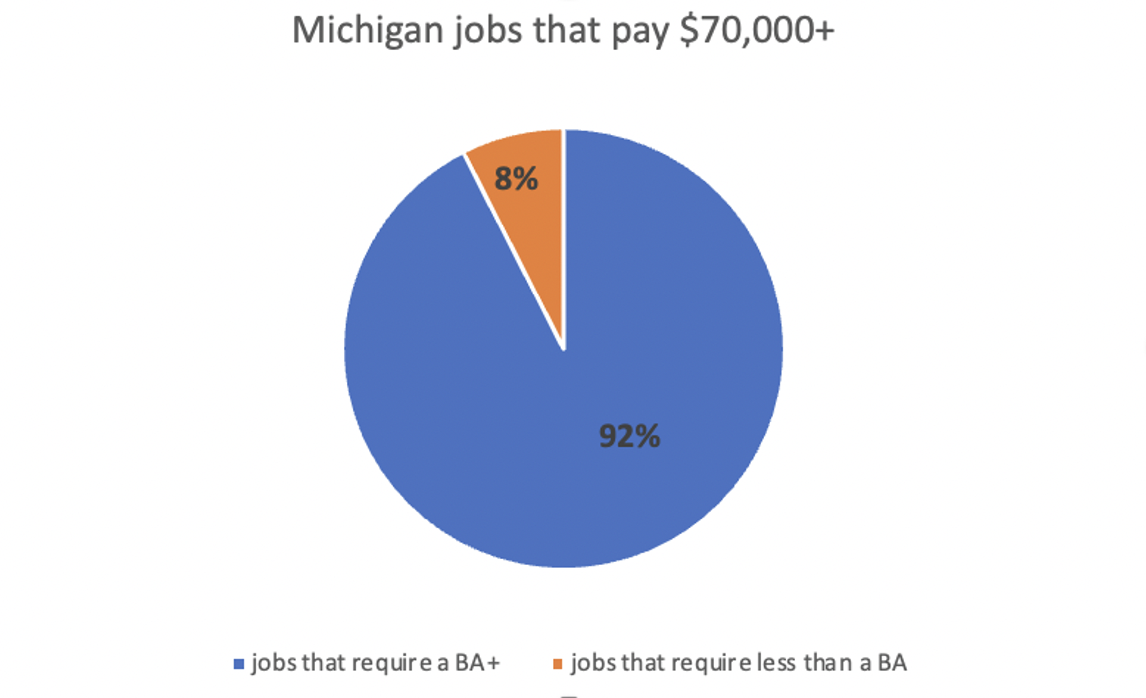

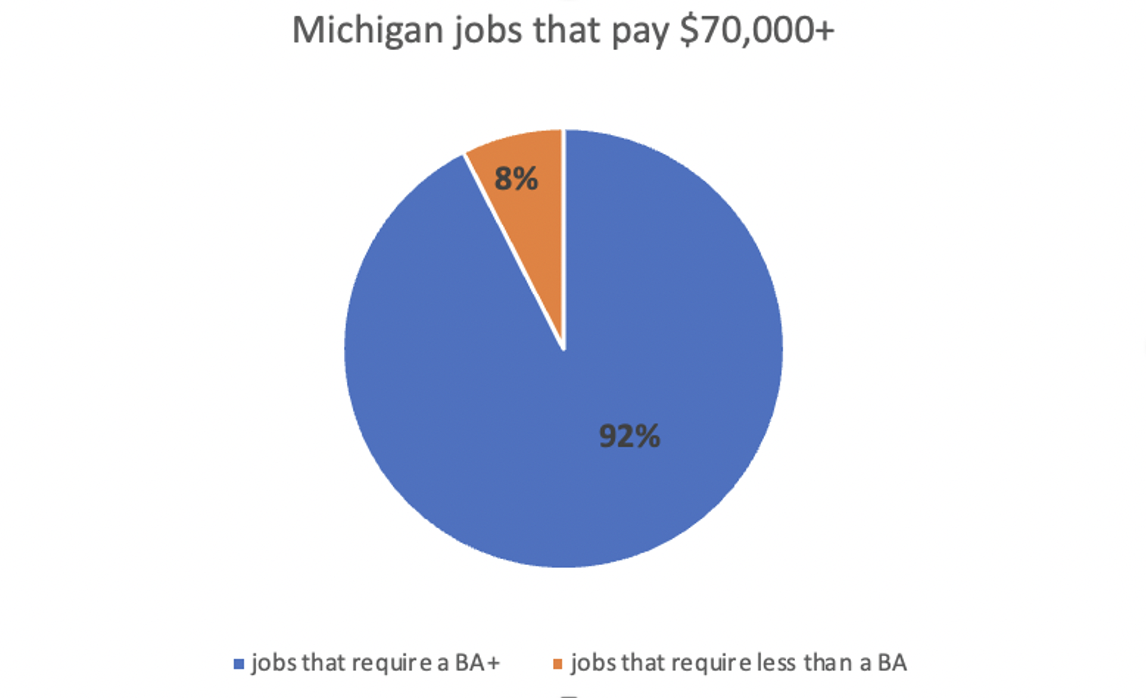

Defining a good job as one that pays at least $70,000 a year further narrows our field of jobs, down to just 892,000 jobs, or 21% of all Michigan jobs. Of these jobs, 825,000, or 92%, require a bachelor’s degree or more. This leaves just 67,000 good jobs, or 1.5% of all Michigan jobs, available to those with less than a bachelor’s degree.

But if you don’t have a bachelor’s degree in today’s economy, the odds of you getting one of those good jobs is actually far worse than that, simply because there are many more people with your same educational credential competing for that small slice of the pie.

Indeed, there are 3.4 million Michiganders between the ages of 25 and 64 with less than a bachelor’s degree, competing, in theory, for those 67,000 good jobs that require less than a BA. This is equivalent to 51 Michiganders competing for every good job that does not require a BA.

Meanwhile the 1.7 million Michiganders between 25 and 64 that do have a bachelor’s degree are competing for 825,000 good jobs, the equivalent of just two folks applying for every good job.

One could argue that this analysis is too blunt – what about all of the sub-BA credentials, like an associate’s degree or a postsecondary non-degree award? Aren’t these sub-BA credentials a pathway to good jobs? Indeed, much of our focus in today’s higher education policy discussions center around these pathways – a four-year degree isn’t for everyone, many will say, but these sub-BA credentials offer a pathway to good jobs.

The data tells a different, and decidedly bleaker, story. Of those 67,000 good jobs that don’t require a BA, the vast majority (83%, or 54,000 jobs) require no education beyond high school. Just 13,000 good jobs require one of these much-promoted sub-BA credentials.

And, again, the competition for these jobs is steep. There are 2.2 million Michiganders over the age of 25 (in this case we are not using a cutoff of 64, based on how the Census data is presented) with an associate’s degree or some college but no degree. This leaves roughly 171 Michigan residents with some college short of a BA competing for each of these good sub-BA good jobs. One could argue that this leaves those with a sub-BA credential with the worst odds of any group of capturing a premium for that additional education in the labor market.

There are nuances of course. The field of one’s degree or credentials matter, and labor markets for particular occupations obviously vary. But the central story the data tell is quite simple: while a relatively small number of overall jobs in the economy today require a BA or more, a bachelor’s degree is all but essential to get a good job in today’s economy.

This is why the figures from the Chamber’s survey are so distressing. For most young people, and parents of young people, a $70,000 a year job is likely pretty close to their conception of a good job – the type of job a young person might want to have, and the type of job a parent might want for their child. And the data shows that a bachelor’s degree is not only very important, but nearly essential to getting a job like this. Yet only a quarter of Michigan voters believe this.

The reasons are many, and I’ll go into some of them in future posts, but a big part of it is that our leaders – both here in Michigan and nationally – are repeatedly sending the exact message to young people that was reflected in the survey: that you don’t need a four-year degree to get a good job. It’s a politically popular message, considering the majority of adults, both in Michigan and nationally, don’t have a four-year degree. There should, indeed, be a path to good jobs for these tens of millions of people as well. But it’s not something you can wish into existence if you say it enough. Our economy, now and into the foreseeable future, will have lots of jobs that don’t require a four-year degree, and the vast majority of those jobs will not pay very high wages – the result of global competition and automation that has driven down the price of certain kinds of work.

The solution – instead of sending false signals about the true nature of the labor market – is to use public policy to make jobs – all jobs – pay more. This was a chief motivation behind our effort to expand the state’s earned income tax credit from 6% to 30% of the federal credit. Many more of these kind of efforts are needed to promote a more equitable economy, and a lot of these initiatives would have to occur at the federal level, where the purse is larger.

But in the meantime, we should not promote false narratives about the true nature of the labor market, and what’s needed to succeed in today’s labor market. Our young people deserve pathways to opportunity, and they need an honest assessment of those opportunities to make wise choices.