Every year, the US Census Bureau publishes estimates of the poverty rate in the U.S. There is the official poverty measure (OPM), which is what we use to determine eligibility for government assistance, and the supplemental poverty measure (SPM), which takes into account the impact of various social safety-net programs on overall poverty. The SPM allows us to measure the anti-poverty impact of various elements of our social safety net, by counting how many more people would clear the poverty income threshold with and without a particular element.

So, which programs are doing the heavy lifting in the fight against poverty?

Every year, the big winner, by far, is social security, the most successful anti-poverty program in US history. But after social security, most of the action comes from refundable tax credits, and, in particular, the Earned Income Tax Credit. Aside from 2020 and 2021, when millions of Americans were kept out of poverty by various pandemic relief efforts, over the past two decades no program has pulled more non-elderly Americans, and more American children, in particular, out of poverty than the Earned Income Tax Credit.

The Earned Income Tax Credit is, as its title suggests, is a refundable tax credit available to low- and middle-income households with earnings from work. Starting with the first dollar earned, the credit phases in as an individual works more, maxing out at around $6,000 for a single parent with two children earning between $16,500 and $21,500. The size of the credit then slowly declines as earnings increase, but doesn’t phase out completely until earnings reach around $53,000.

Estimates vary, depending on what income threshold one uses and how one estimates receipt of the credit, but every year the EITC reliably pulls between 3 and 6 million Americans above the poverty line. Some researchers argue these estimates understate the ultimate anti-poverty impact of the policy, because they only capture the mechanics of receiving the additional income from the credit itself, but not the behavioraleffect generated by the policy. A large body of research suggests that the EITC boosts labor force participation by “making work pay,” and that this employment effect might expand the antipoverty impact of the policy by as much as 50 percent.

This is important because for state policymakers who care about reducing poverty in Michigan and stabilizing Michigan households, we don’t have to do much searching to find out what works. And through Michigan’s state EITC, we have a powerful lever we can use to amplify the poverty reducing impact of the EITC.

While this all sounds very good, discussions of poverty measurement at the population level can often feel abstract. So, more concretely, what might ambitious state EITC policy mean for Michigan families?

At present, expanding the size of the EITC is a priority for Governor Whitmer and for legislators, on both sides of the aisle. Bills have been introduced to return the state credit to 20% of the federal credit, where it sat during the Granholm administration, or go even further, to 30% of the federal credit. Other states, including Minnesota, New Jersey, and Maryland, sit near or above 40%.

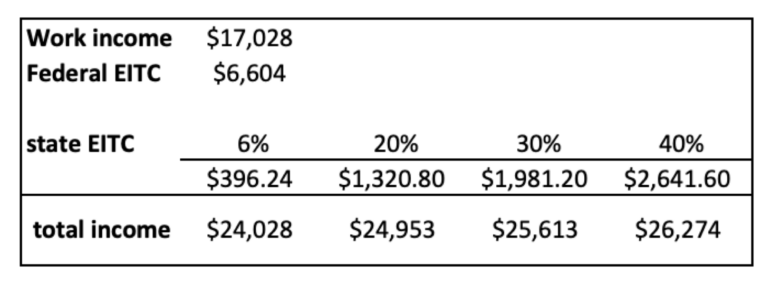

The chart below shows the size of the various credits under these policies for a case example of a single mother with two children, earning $11 an hour, and working 30 hours per week. This mother would earn roughly $17,000 from work, placing her well below the official poverty threshold for a family of three (which is roughly $25,000). Our case parent would receive the maximum federal EITC for her family size ($6,604). A 20% state credit would mean an additional $1,320, and would place this household above the poverty threshold. A 30% state credit would add nearly $2,000 to the federal credit, and a 40% state credit would push our case parent’s total refund above $9,000, providing her with a more than 50% boost on her take-home pay.

These extra dollars matter a great deal because research suggests many EITC recipients use their refunds to pay down debt, make investments in housing and education, or purchase a used car – purchases and payments they might not otherwise be able to make. In this way, a large EITC refund provides a unique opportunity to not only help families achieve greater financial stability today, but to make critical investments in their future.

In short, the federal EITC has been, and continues to be, one of the most powerful anti-poverty programs we have, boosting employment and household incomes. But when paired with an ambitious state EITC, the policy becomes that much more transformational, and potentially life-changing, for Michigan families.