To us the data are clear: Michigan has a two-tier economy. This two-tier economy is prevalent across all of Michigan and across all races and ethnicities. And it predates the pandemic, as evidenced by the Michigan Association of United Ways findings that in Michigan’s strong 2019 economy nearly four in ten Michigan households were unable to pay for basic necessities.

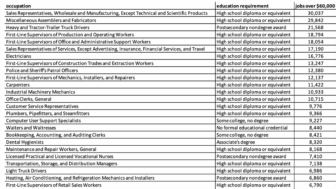

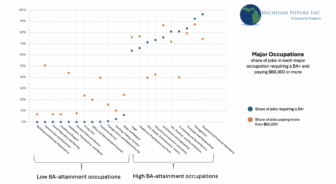

The core reason 38 percent of Michigan households cannot pay for basic necessities is that the economy is producing too many low-wage jobs. In the robust 2019 economy 59 percent of Michigan payroll jobs paid less than what it takes to be a three person middle class household ($47,000).

This is structural. Lots of businesses that employ lots of people have business models based on low-wage workers. We are not growing our way out of too many low-wage jobs. The reality is that no matter how strong the economy, there will be lots of low-wage jobs.

The pandemic also made clear that these “essential” workers live paycheck to paycheck not because they are irresponsibly buying “unnecessary” luxuries, but because they are in low-wage jobs that leave them struggling to pay for the necessities. The reality is that most of those struggling economically, in good times and bad, are hard-working Michiganders. Who like us get up every day and work hard to earn a living.

In this post I want to look at what the post-pandemic labor market says about the structural reality of lots of low-wage jobs. The current labor market is experiencing real labor shortages: more demand than supply. Particularly in low-wage jobs.

Economic theory tells us that this should drive up wages. The good news is that it has. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s wage growth tracker reports that the 12 month growth in median wages in May 2022 was 5.0 percent for all workers and an even higher 6.7 percent for bottom quartile workers.

The question is with a 6.7 percent increase in wages can low-wage workers pay for basic necessities. A terrific new report by Brookings, entitled Profits and the pandemic: As shareholder wealth soared, workers were left behind, attempts to answer that question.

The report “examines the pay practices and financial outcomes at some of the nation’s best-known companies in sectors spanning retail, delivery, fast food, hotels, and entertainment. Together, the 22 companies employ more than 7 million frontline workers—more than half of whom are nonwhite.”

The 22 companies are: •Albertsons •Amazon •Best Buy •Chipotle •Costco •CVS •Disney •Dollar General • FedEx • Gap •Hilton •Home Depot •Kroger •Lowe’s •Macy’s •Marriott •McDonald’s •Starbucks •Target •UPS •Walgreens •Walmart

The report uses $37,000 as a living wage. A calculation of what it takes a family of two adults and two children to pay for rent, food, child care, health care, transportation, and taxes. (This is a substantially lower threshold than our calculation of $47,000 to be a Michigan middle class family of three.)

Even with that lower threshold Brookings concludes that post pandemic “overall, companies made little progress on meeting the standard of a living wage“. More specifically Brookings found:

Of the 22 companies we analyzed, there are just five companies—Amazon, Best Buy, Costco, Marriott, and UPS—that we can say with a high degree of confidence paid at least half of their workers a living wage as of October 2021, compared to four companies pre-pandemic. We believe Disney and FedEx may also meet that bar, but cannot confirm with the data available. It is very unlikely that any of the remaining 15 companies paid at least half of their workers a living wage.

Because wages are so low, we focus on whether companies pay at least half their workers a living wage. It is notable that despite the fact that more than half of companies increased their minimum wages during the pandemic, not one pays a minimum wage today that meets the living wage standard. In October 2021, $15 per hour is a full $2.70 per hour lower than a living wage. In fact, an hourly worker in October 2021 would need to earn more than $16 per hour just to have the same purchasing power as $15 per hour at the start of the pandemic. (The same worker would need to earn $16.50 in February 2022 to have the same purchasing power.) Only Costco has a minimum wage today ($17 per hour) that is close to a living wage for a full-time worker.

Because they started at a low base, some of the companies with the biggest wage increases still have very low pay today. This is especially true in the fast-food industry. For instance, McDonald’s has garnered positive media coverage for raising pay for employees at company-owned stores by 7% in real terms. In 2021, McDonald’s raised its minimum wage to $11 per hour and its average wage for nonsupervisory employees to $13. The company has pledged to raise average (not minimum) pay to $15 by 2024. At a $13 average hourly wage, a McDonald’s employee working 20 hours per week (most McDonald’s employees work part time) would take home less than $14,000 a year—an income so low it would put a household of two under the federal poverty line.

Both our analysis of the Michigan labor market and this Brookings report should make clear that left on its own the market will not solve the reality that too many jobs do not pay enough for many workers to earn enough to even pay for the basics. That policy change is necessary to have an economy that provides rising income for all. An economy that as it grows benefits all. Brookings gets it exactly right when they conclude:

The growing inequality of the past decades grew out of a power imbalance. As workers’ power declined, they had limited ability to demand fair treatment. Short of threatening to quit, they had to hope that executives would choose to share gains with them and mitigate their losses. But with executive compensation increasingly tied to company performance that is measured quarterly—not for the long term—the system’s incentives discourage investment in workers.

Building a more equitable system will require a more equitable balance of power. Rather than hoping companies will exercise their discretion to benefit workers, the U.S. needs laws, institutions, and policies requiring, pressuring, and incentivizing them to do so. Policy reforms are needed to enable labor to reclaim power. These reforms span labor law, regulation of working conditions (including wages), corporate disclosure, corporate governance, and more.