![]() The policy agenda we released in April is built around public investment. Years of cuts to our education system, our cities, to public services, and to our social safety net have placed a drag on the economy and lowered living standards for Michiganders. To put Michigan on a path to prosperity, public investment is required.

The policy agenda we released in April is built around public investment. Years of cuts to our education system, our cities, to public services, and to our social safety net have placed a drag on the economy and lowered living standards for Michiganders. To put Michigan on a path to prosperity, public investment is required.

Whenever the prospect of public investment is raised, however, the question that immediately follows is inevitably “how are you going to pay for that?” And the answer, simply enough, is that we have to raise revenue.

Disinvestment in Michigan

The extent of state disinvestment in critical public services over the past twenty years is astounding: we’ve cut $1 billion from higher education since the early 2000s, creating massive obstacles to student access and success; the minimum foundation grant for K-12 students has dropped by over $1,000 in real terms since 2002, preventing non-affluent districts from making needed investments to improve student outcomes; the state has diverted $6.2 billion from municipal revenue sharing since 2002, contributing to fiscal distress in cities across Michigan; and we’ve wholly disintegrated our social safety net.

In the pursuit of anti-tax policies, we’ve failed to invest in the drivers of today’s economy, including higher education, vibrant central cities, and an active and engaged workforce.

How much money do we have? How much money could we have?

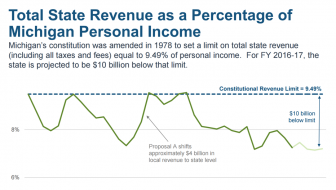

Michigan has an annual budget of roughly $54 billion, with roughly $30 billion coming from state revenue and the rest coming from federal sources. This $30 billion in revenue is roughly 7% of the state’s total personal income, 2.5 percentage points below the constitutional revenue limit of 9.5%.

This additional 2.5% we could add to the state offers ends up equating to quite a bit of money: $10 billion. An additional $10 billion in state revenue would be equivalent to nearly doubling the state’s general fund, giving the state more than enough resources to appropriately share revenue with financially strapped cities, support education, maintain our roads and water systems, and properly fund social services.

And this level of revenue isn’t a stretch – the state collected up to the constitutional revenue limit in the mid-90s through the early 00s, as you can see in the chart below from Michigan’s House Fiscal Agency.

Where will the money come from? The case for a graduated income tax

When it comes to raising revenue, we can’t get too creative. Ninety-four percent of the School Aid Fund and General Fund come from four major state taxes: the individual income tax, sales and use taxes, business taxes, and state property taxes. The personal income tax and the sales and use tax are the largest sources of revenue among these, by a good margin.

One oft-floated idea for raising revenue is to expand the sales tax to cover more services, which are largely excluded from taxation. The argument goes that as services take up a larger and larger portion of consumer spending, we’re leaving a lot of money on the table by not taxing these expenditures. However, due to the regressive nature of the sales tax, relying on a sales tax expansion to raise revenue may be less than ideal from an equity standpoint.

On the other hand, a convincing equity argument can be made for the adoption of a graduated income tax. While non-affluent families in Michigan have failed to see their incomes rise over the past forty years, those at the top of the income distribution have done very well. Research by Michigan State University economist Charles Ballard found that between 1976 and 2013, the top 20% of Michigan households saw their incomes rise by over 20%, with the top 10% seeing an increase of almost 40%. The bottom 70%, on the other hand, saw incomes rise by at most 5%, with incomes either stagnant or declining for the bottom 50% of households. A graduated income tax would ask a bit more from those who’ve done well, while not inflicting pain on the vast majority of Michiganders who’ve seen a decline in their standard of living.

This is far from an out-of-the-box idea – Michigan is actually one of only six states with no progressivity in its income tax. And contrary to the narrative that tax cuts lead to economic growth, it’s states with graduated income taxes like New York and Minnesota – who have enough revenue to fund higher education and central cities – and the most prosperous state economies.

Aside from the equity argument, a progressive state income tax also makes sound economic sense. Because state taxes paid can be deducted on your federal taxes, the rest of the country effectively subsidizes higher state tax rates.

Not investing is not an option

Moving to a graduated income tax is just one idea to make the investments needed to put Michigan on a path to prosperity – there are surely others. But not investing is not an option. The things that actually drive a state’s economy – a vibrant knowledge economy, strong central cities, an active labor force – require investments in higher education, in cities, and in a strong safety net that helps all Michiganders find good work at a good wage.

We’ve had plenty of years to test out the strategy of tax cuts and disinvestment from core public services, and the results speak for themselves. It’s time for a new strategy.