I’m generally not a fan of measuring a college’s value by the incomes of their graduates. If a high proportion of a school’s alumni enter a lower-paid field like social work, I don’t think this should count against the college. In addition, simply looking at salary data ignores the significant non-pecuniary benefits of getting a college degree.

That said, a set of data on earnings by college released last month from economist Raj Chetty and others – who’ve published a series of recent studies documenting mobility and opportunity in America – is worth paying attention to. Their data is interesting because using anonymous tax records they were able to track a college’s impact not just on earnings, but on mobility. They’re able to measure whether or not a student who grew up in the bottom income quintile and attended a particular college was able to move up to the middle-class as adults.

In a summary of the research for the New York Times, David Leonhardt charted the colleges across the country that best achieve this goal of upward mobility, documenting the percentage of students who enter each college from families in the bottom income quintile (a household income of below $25,000), but ended up in the top three-fifths of earners by the their early thirties. For a school to be considered, at least 10% of each class needed to be from the lowest income quintile (a sign of commitment to broad access), and they needed to enroll at least 500 students in each cohort (to show they were doing this work at scale). It should be noted that the data sets include students who went to a particular college for the bulk of their college career, even if they did not graduate from that school.

This is a wonderful analysis because it measures a college’s ability to deliver on what should be one of its core missions – to serve as an engine of mobility for low-income students. So using the publicly posted datasets for every college in the country, I ran a similar analysis for Michigan colleges, to see how our institutions are doing in providing economic opportunity for all Michiganders.

The first thing to note is that Leonhardt’s analysis is impossible in Michigan because our four-year colleges don’t enroll enough students from the bottom income quintile. Only three four-year colleges in Michigan drew more than 10% of their students from the bottom income quintile: Wayne State, U of D Mercy, and Olivet College (the data looks at students that entered college in the late 90s).

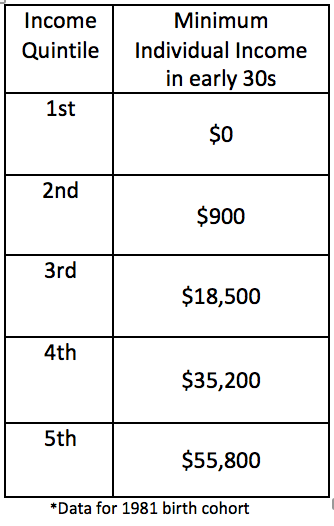

My analysis also differs from Leonhardt’s in that I analyzed the percentage of students at a college who were able to move from the bottom income quintile to the top two, rather than top three income quintiles. The reason for this is that those in the third quintile actually aren’t making very much money. An individual in the third income quintile could be making as low as $18,500 a year – not what any college would consider a success. The minimum income for someone in the fourth quintile, on the other hand, is closer to $35,000, a better measure of economic security.

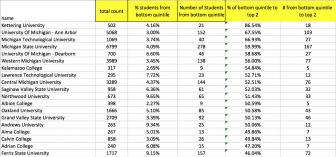

With these caveats in mind, below is a chart that shows the percentage of bottom quintile students that end up in the top 40% of earners by their early thirties for colleges in Michigan. I’ve listed the top 20, but be sure to note that those most successful on this metric enroll relatively few bottom quintile students: 4% at Kettering, 3% at U of M, 4% at Michigan State. The column on the far right shows the average number of students in each cohort at the college that make the jump from the bottom quintile to making a decent salary as adults.

Seen through this lens, a couple things become clear. The first is that there are a fair number of schools in Michigan in which students from the bottom quintile who attend are more likely than not to be in the top 40% of earners by their early 30s. Many students in Michigan are indeed using postsecondary education as an engine of economic mobility.

On the other hand, we’re not doing nearly as well as we should be. At almost every college, including prestigious schools like U of M and MSU, a significant chunk of students that enroll don’t make it to the top 40%. For these students, college did not provide them a ticket to economic security. The key thing to remember here is that this data encompasses all students that attended the university, both those that graduated and those that didn’t. I’d be willing to bet that the vast majority of students that failed to earn an annual salary of at least $35,000 by their early 30s were those that did not end up with a degree. The median salary for BA holders in 2015 was $51,000.

This finding argues for more transparency from colleges on the performance of their low-income students. We already have publicly available data on the graduation rates for minority groups, but we don’t have the same data by income. It’s entirely possible that while U of M’s graduation rate is 90% for the entire student body, the graduation rate for bottom quintile kids is far lower, with the kids that graduate earning solid footing in the middle class, and the kids that don’t left to struggle without a degree.

The other clear finding is that we need to continue to broaden access to our most selective colleges and universities for our poorest families. The problem of access is multifaceted, and encapsulates the need for quality k-12 preparation and college counseling, which will enable more low-income students to qualify for top tier schools, and then apply and matriculate to them, rather than undermatching. But our state’s highly selective colleges also have a role to play, perhaps by actively recruiting low-income students, relaxing SAT/ACT requirements in favor of good high school grades (which are shown to be predictive of college success), and ensuring low-income students are afforded the financial resources needed for them to be successful. Both U of M and MSU have made efforts in these directions over the past few years, but we need to broaden and accelerate these efforts.

In my next post I’ll analyze another metric the Times used in their analysis, which they call the “mobility rate.” Once again, we’ll see that Michigan’s postsecondary institutions have a lot of room for improvement.