When people talk about Michigan’s failing education system, or talk about Michigan being 44th in education, or set a goal for Michigan to be a “top ten” state in education, they are generally referencing a single data point: the average score by Michigan 4th graders on the NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) reading exam.

On the 2024 NAEP, just 25 percent of Michigan 4th graders scored at or above the NAEP “proficiency” threshold in reading. This has raised the alarm bells of Michigan’s political and business leaders, who, based on this data, claim that 75 percent of Michigan 4th graders can’t read, and have therefore called for a slew of reforms. This is a crisis that demands action, they say.

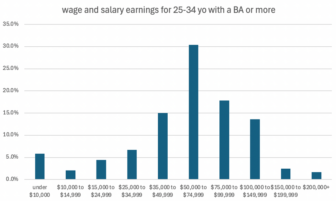

We certainly believe that Michigan’s education system is in crisis and we certainly believe action is required. However, as outlined in two previous posts, our reasons differ from the mainstream narrative. Michigan’s education system is in crisis not because too few 4th graders are proficient on NAEP, but because far too few students graduating from our K-12 system go on to complete a bachelor’s degree. And, perhaps contrary to what a casual observer might believe, Michigan’s 4th grade reading scores tell us next to nothing about whether or not those students will be prepared to pursue and complete a four-year degree after leaving high school.

But while we generally think there ought to be a lot less focus on NAEP and 4th grade reading scores in discussions around our K-12 education system, in this post I want to focus in on NAEP to address two major misconceptions, about what the NAEP scores are telling us, and about how we can and should change schooling in Michigan if we are serious about improving 4th grade NAEP scores. And, as it turns out, those changes align with our broader goal of creating a system that prepares students for college and career in an ever-changing knowledge economy.

What are NAEP scores telling us?

First, what are these scores telling us? On the NAEP website you can not only see students’ average scale scores and the share of students scoring above “basic” and “proficient” thresholds, but you can also drill down to individual sample assessment items to see the share of students, nationally, that got each question correct or incorrect. And the first thing you notice here is that based on responses to these individual questions, most students can, in fact, read.

The first four sample questions all ask students to “recognize” something – details, plot elements, character motivation – from a short passage they were instructed to read prior to answering the question. In the questions I examined, students were asked to read “The Bell of Atri,” an Italian folk tale,and answer very basic multiple-choice questions about the core factual elements of the story. For example, one question asks:

In the story, why did the soldier decide to get rid of the horse?

- He did not have enough room for all his horses

- He was moving into town and did not need a horse

- He thought he and the horse had been together too long

- He thought the horse was too old to be useful

The correct answer is D, something that you would easily understand if you read the story. And this was easy to understand for most American fourth graders as well. 75% of students got this one correct. In fact, on the four questions that ask students to simply recognize basic elements of the story, between 60% and 75% of test takers answered the questions correctly. Students’ relative success on these questions demonstrate that most fourth graders can, in fact, read; that is, they can decode and comprehend enough words to understand enough of what’s going on in a story to be able to answer simple questions related to that story.

Where things get more difficult for most students is when the task turns from “recognize” to “interpret”, “describe”, or “evaluate.” On the four sample questions that asked students to deploy these higher order skills, just 27%to 40% of students answered the questions correctly. Three of these questions were open-response questions, where students had to make a claim about the passages they had just read, and then back up that claim with evidence from the text.

For example, one question simply asks students the following question:

“Who do you think is the most important character in the story “The Bell of Atri”? Use specific information from the story to support your answer.”

There is no right answer to this question. Rather, there is a range of acceptable answers, so long as the student uses evidence from the text to support their claim. And students aren’t expected to write an essay – just a sentence or two would suffice. But to answer the question correctly students need to demonstrate comprehension of the story, make a claim, and back up the claim with evidence. This is, in miniature, the kind of task students will be asked to do repeatedly in college.

Only 27% of American students got this question correct. In contrast to the “recognize” set of questions, most U.S. students are hopeless on these questions testing higher order skills.

Why this matters: the science of reading and what often gets left out

The reason this is so important is because understanding what kinds of questions students generally get right and wrong has massive implications for how our K-12 classrooms ought to change. In response to Michigan’s low reading scores, most political and business leaders have called for Michigan schools to implement so-called “science of reading” practices. The science of reading is a short-hand for a range of research-backed literacy practices, but its popularly associated with a focus on decoding through phonics and phonological awareness – building in students a deep understanding of syllables, letter sounds, and how they blend together to form words.

Clearly, phonics instruction is critical. However, as evidenced by students’ responses to the NAEP sample items outlined above, it’s not enough. On the 2024 NAEP, most students were able to decode and comprehend enough words to be able to answer basic questions about a reading passage. What they couldn’t do was do anything with the content they just read. If our early literacy “crisis” simply prompts lawmakers, and therefore schools, to double their focus on decoding and test prep exercises, we will make no growth on a broader set of higher order skills. These skills end up being both those that will be required to gain proficiency on NAEP, and, more importantly, to enter a world of work that values interpretation, description, and evaluation far more than it does recognition.

A pedagogy tailored to these higher order skills would need to go far beyond simply ensuring all teachers are deploying phonics-based instruction. Students would need to get ample practice interpreting, describing, and evaluating a text, and backing up their claims with evidence. They would need a curriculum rich in vocabulary and content, because the more background knowledge a student has about the world, the better they will comprehend what they read. In our K-12 classrooms there would need to be a lot more writing, a lot more discussion; a lot more of teachers asking students how they know this or that, where is the evidence in the text; and a lot more genuine engagement with material, rather than school serving as a test-prep center. This vision of K-12 education is both much more rigorous than commonly offered reforms, and more engaging for students as well.

All this leads back to our overall view on Michigan’s education system. The focus of our education system should not be on 4th grade test scores. We should be far more ambitious. The focus of our education system should be on building the skills, mindsets, and competencies needed to complete a four-year degree (because a four-year degree is the surest route to a good-paying job) and thrive in a forty-year career in a rapidly changing knowledge economy. And, it turns out, if we focus more on those skills and mindsets – which involve a whole lot more interpreting, describing, and evaluating than simply recognizing – NAEP scores will probably go up too. But that is just a happy accident.