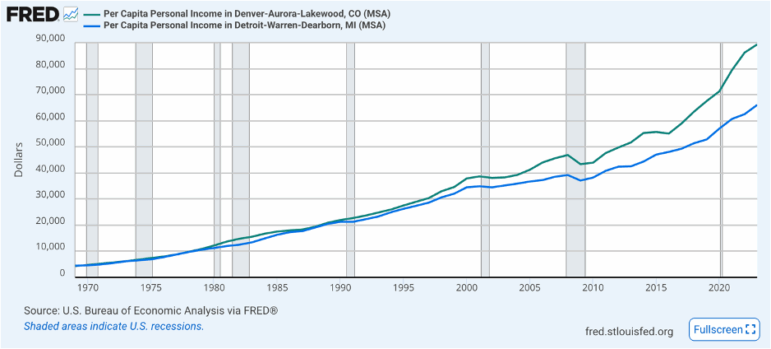

Metro Detroit has gone from one of the nation’s most prosperous big metros to one of its poorest. In 1999, Detroit’s per capita income was 12 percent above the nation’s; today, it is five percent below.

How did this happen?

In today’s talent-driven economy, the prosperity of a region is dependent on the educational attainment of the people in that region. Where you have high concentrations of highly-educated talent, high-growth, high-wage, knowledge-based enterprises locate, expand, and are created. So the economic development goal in today’s economy is to attract highly-educated talent; and in particular, because they are the most mobile, highly-educated young talent. The new reality is that talent attracts capital, and quality of place attracts talent.

Over the past twenty-five years, metro Detroit has not attracted talent at scale. And the primary reason for this is that its principal city, Detroit, has not attracted talent at scale. Young people, and highly educated young people in particular, continue to flock to vibrant central cities that feature dense, walkable, amenity-rich neighborhoods. Despite Detroit’s still nascent economic resurgence, it still lacks these kinds of talent magnet neighborhoods.

Detroit vs. Denver

How do we change this? We could do much worse than to follow the example of Denver. One can make a strong case that Denver is the American region that has understood best the new reality that talent attracts capital.

In 1990 metro Denver and metro Detroit had roughly the same per-capita income – $21,295 for metro Detroit and $21,972 for metro Denver. Today, the per-capita income in metro Denver is more than $23,000 higher than it is in metro Detroit – $89,297 to $66,098. Denver’s per-capita income is nearly 30 percent above the nation’s while Detroit’s is five percent below.

The reason, of course, is that metro Denver has far higher levels of educational attainment than metro Detroit. Fifty percent of adults in metro Denver have a bachelor’s degree or more, compared to 34.5% in metro Detroit.

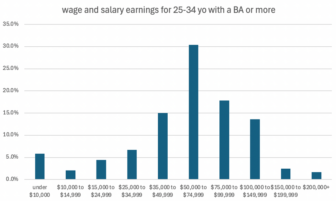

As noted above, because highly educated young adults are the most mobile segment of society, and they tend to congregate in vibrant central cities, a core driver of educational attainment at the metro level is the number of young professionals (25-34 year olds with a bachelor’s degree) in a metro’s central city. Since 2010, Denver has nearly doubled its number of young professionals, from 59,316 to 112,247. An astonishing 67% of young adults in Denver have a bachelor’s degree.

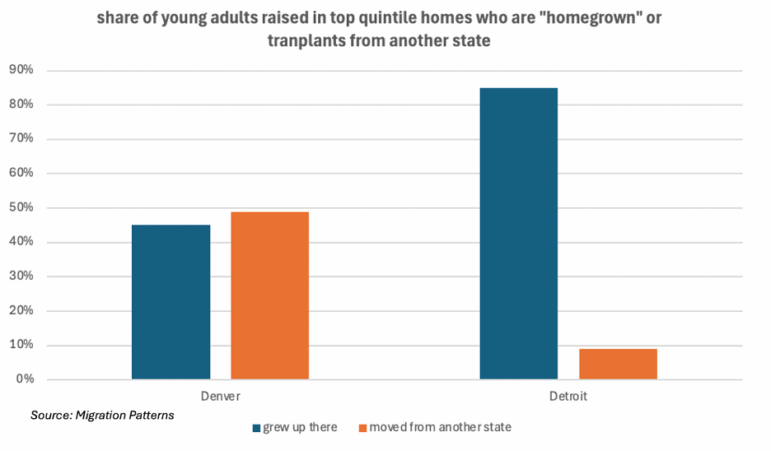

Most of these additional Denverites are transplants. Data from Migration Patterns shows that less than half of young adults in metro Denver raised in higher income homes (here household income is used as a proxy for college education) actually grew up in the Denver area, while 49% came from other states, many from the metro regions of Chicago, LA, DC, Minneapolis, and Detroit. Denver became a talent magnet, and young professionals flocked there from across the country.

The picture is much different in Detroit. Less than 25,000 young professionals live in Detroit, and just 25% of all young adults in the city have a bachelor’s degree. While the young adult population raised in higher income homes of metro Denver is largely made up of transplants, most young adults raised in higher income homes in metro Detroit (85%) grew up in metro Detroit. Detroit’s problem is not retention of young people as much as it is attraction of young people.

While young professionals make up 16% of Denver’s population, they make up just 4% of Detroit’s population. If Detroit’s population had the same share of young professionals as Denver’s, there would be an additional 75,000 young professionals living in the city.

The Denver story: rail transit and talent magnet neighborhoods

So how did Denver become a talent magnet? First, they went big on rail transit. The region now has the kind of rail transit system the Detroit region can only dream of, with a line running from the airport to downtown, throughout city neighborhoods, and into suburban communities. Transit oriented developments – new dense, walkable, neighborhoods, complete with housing and small businesses – have sprouted up along rail stops, and downtown Denver has exploded with development.

In addition to rail transit, Denver has prioritized building dense, walkable, vibrant neighborhoods across the city. It is a city’s neighborhoods – densely packed with young professionals, amenity-rich, with recreational, arts, and cultural offerings – that are the main attraction for young talent.

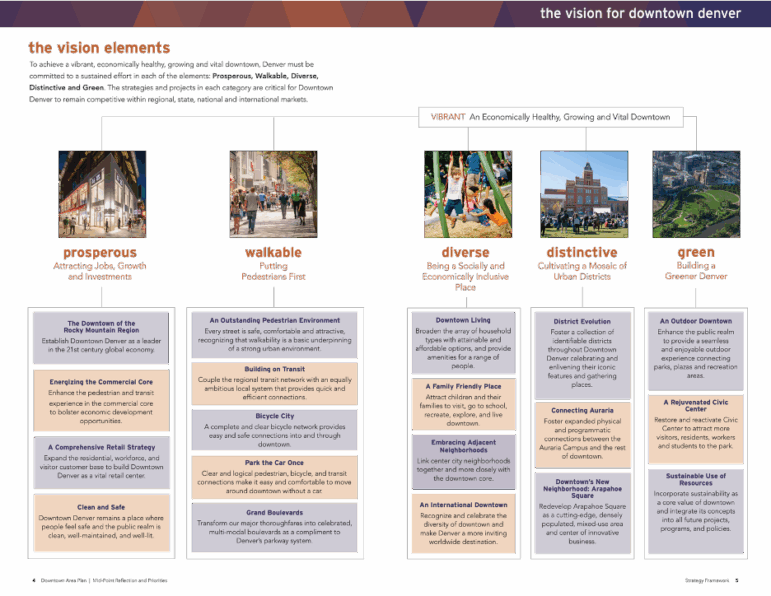

Economic development leaders in Denver have long understood this, and made the creation of talent magnet neighborhoods a priority for the city. In 2007, the Downtown Denver Partnership put out its vision for downtown Denver, copied below. The themes of walkability, the expansion of amenities, the cultivation of distinct neighborhoods, and the prevalence of outdoor recreational opportunities are evident throughout. It’s a citywide plan designed to create the kinds of neighborhoods/districts that attract young talent.

It’s not the mountains

When we use Denver as an example of the kind of place that Detroit or Grand Rapids ought to model itself after, folks will often say that it was the mountains and natural beauty that attracted so many young folks to Denver, not the rail transit or the city’s vibrant, walkable neighborhoods. What we like to point out is that the mountains were also there in 2005, when the city had just 45,000 young professionals. It was only after rail transit and an explicit focus on building dense, walkable, vibrant neighborhoods that the city emerged as a talent magnet.

If Detroit hopes to attract talent at anything like the scale that Denver has over the past decade, metro Detroit needs a robust rail transit system, and the city needs to intentionally build dense, walkable, amenity-rich neighborhoods. The example of Denver makes clear that in order for that to happen, we need leaders – in Lansing, in Detroit city government, in the Detroit business community, and in suburban communities across the region – to champion rail transit as their central cause, over and over again, for years. And we need these leaders to prioritize building talent magnet neighborhoods in our central cities as the economic development imperative in today’s economy.

Last year, the state created the Michigan Talent Partnership, based on a proposal we designed – a competitive grant fund that calls for Michigan cities to create the kind of dense, walkable, vibrant neighborhoods/districts that Denver has been building since the mid 2000s. It’s a start, but we will need much more of this kind of activity if we are to build a more prosperous Michigan.