In my last post, I explored the data in the latest ALICE report which showed that the share of Michigan households that did not earn enough to pay for basic necessities increased sharply between 2021 and 2022. The core reason for the increase is that the pandemic-induced social safety net erected in 2020 and 2021 – periodic “stimulus payments,” expanded unemployment assistance, an expanded child tax credit – fell away in 2022. So, even though the economy was much improved in 2022, and many more people were employed, the share of households facing material hardship increased because of a diminished social infrastructure.

The removal of pandemic-era safety net programs was so broadly felt because the pandemic safety net was fundamentally different from our traditional safety net. Whereas our traditional safety net is means-tested (focused only on those with low incomes), program-based (meaning you have to apply to receive assistance), and in-kind (i.e., SNAP benefits for food, housing vouchers for housing, etc.), the pandemic-era safety was nearly universal, was cash-based, and was largely distributed through the tax code. What this means is that while most traditional safety net programs serve a small share of non-affluent households, the pandemic-era safety net served the vast majority of non-affluent households. In other words, the pandemic-era safety net achieved scale.

This idea of scale is worth dwelling on in light of the latest ALICE update. Because while some believe we have a vast social safety net that adequately serves those households in need, the reality is most safety net programs serve only a small fraction of households facing material hardship.

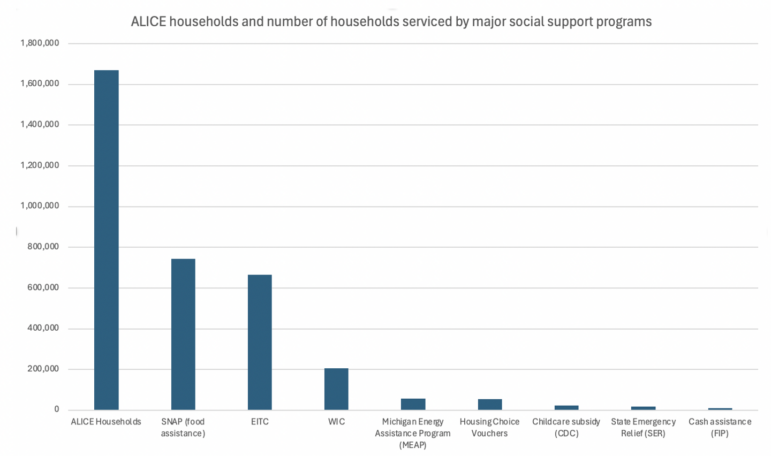

The chart below illustrates the limited reach of much of our social safety net. The first bar shows the 1.67 million households in Michigan with incomes under the ALICE threshold. The remainder of the bars show how many households receive assistance from various safety net programs meant to help pay for household necessities, like food (SNAP), housing (Housing Choice Vouchers), and childcare (state childcare subsidy, known as the child development and care program, or CDC).

As one can see, most of these programs struggle to get to any sort of scale. SNAP benefits cover a large number of households because SNAP is federally funded and, particularly for households with children, is the one element of our safety net that comes close to being an entitlement, where anyone who is eligible is served. Similarly, the WIC program (or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children), which provides supplemental nutrition supports for pregnant women and young children, gets to decent scale through sufficient federal funding to cover all eligible participants.

But beyond those two cash-like, near-entitlement programs, the only piece of our social infrastructure that gets anywhere close to covering a meaningful share of the ALICE population is the Earned Income Tax Credit and its companion state credit here in Michigan known as the Working Families Tax Credit. Nearly 700,000 Michigan households receive the federal and state EITC.

Aside from these elements, it’s nearly impossible to find a safety net program that gets to anything approaching the scale of need. For example, housing is often the most significant cost facing non-affluent households; yet the central program designed to help defray the cost of housing – the Housing Choice Voucher program – reaches just 55,000 Michigan households, or roughly 3% of all ALICE households. So few households are served both because the program is notoriously underfunded, and because families often face a whole host of obstacles in actually using their vouchers to secure a place to live.

Another example is childcare. Childcare is very expensive. The average cost of center-based childcare in Michigan is more than $11,000 annually – a figure that is nearly impossible for non-affluent families to pay out of pocket. Yet the central program for helping families pay for care reaches just 24,000 households in a given month. As is the case with housing vouchers, the limited scale of the childcare subsidy program is the result of inadequate funding and the bureaucratic implementation hurdles that accompany nearly any social service program.

The list goes on. Roughly 75,000 households (~4% of ALICE households) receive assistance with their utility bills through the Michigan Energy Assistance Program (MEAP) and the State Emergency Relief (SER) Program. Just over 11,000 households (0.6%) receive cash assistance, or what used to be known as cash welfare. Putting it all together, one is left to conclude that hundreds of thousands of households unable to meet their basic needs receive no assistance from government to help them do so.

Refundable tax credits can get to scale

The inability of most government programs to serve all those in need is one reason we have been pushing to expand the use of fully refundable tax credits here in Michigan. As noted earlier, aside from fully funded federal programs, refundable tax credits are the only way we can deliver assistance to households in need, at scale. To qualify for most public assistance programs, applicants need to make appointments with caseworkers, fill out long applications, verify their income in a dozen different ways, report any changes in income, and not forget to renew their benefits every year. Because most public assistance programs are not funded at levels high enough to serve all those in need, even if one gets through the application process and qualifies for a program, there is no guarantee they will receive assistance. And then even if one does receive assistance, some programs – like the housing choice voucher program and child development and care program – come with additional implementation barriers that make it difficult for the person in need to access that assistance.

Distributing aid as cash, through the tax code, can avoid many of these barriers that prevent programs from getting to scale. There are no implementation barriers, because households are simply mailed a check. Because it’s structured as a tax cut or refund, all those who qualify will receive assistance. And while filing one’s taxes is not painless, its preferable to applying for social assistance programs. Research has shown that the act of filing taxes instills pride and a feeling of civic participation, whereas applying for public assistance can engender feelings of shame and embarrassment. Research has also found that roughly 80%of households eligible for the EITC actually file their taxes and receive the EITC. While this leaves a lot of room for improvement (20% of households missing out on benefits they qualify for is still a policy failing), this rate of participation in the EITC is far higher than that of most other public assistance programs, for the reasons noted above (the one exception, again, is SNAP, where the share of eligible households participating is quite high). And by supporting the work of non-profit tax preparation sites, like the Accounting Aid Society, we can push this figure higher.

The point is, if we hope to reach a large share of non-affluent households with additional assistance, the best way to do it is through further expansions of refundable tax credits. Programs are hard to apply for, narrowly defined, and rarely fully funded. Refundable tax credits are easier to apply for, cash-based (can be used for a broad array of needs), and can get to scale. And when 41% of Michigan households don’t earn enough to pay for the necessities, getting to scale is essential.