Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell made clear in recent Congressional testimony that a strong safety net is the not the cause of the decline in labor force participation. In a terrific article about Powell’s testimony, the Washington Post writes:

U.S. senators asked Federal Reserve Chair Jerome H. Powell about labor force participation this week, especially after Powell said getting more people into the job market is a “national priority.”

In response, Powell told senators to blame the education system and the opioids epidemic, not welfare.

“It isn’t better or more comfortable to be poor and on public

benefits now, it’s actually worse than it was,” Powell said.… “It’s very hard to make that connection, and I’ll tell you why,”

Powell told (Senator John) Kennedy. “If you look in real terms, adjusted for inflation, at the benefits that people get, they’ve actually declined,

during this period of declining labor force participation.”

Powell’s assessment is aligned with the lessons we have learned from Minnesota, the Great Lakes’ most prosperous state. That there is little or no evidence that a too-generous safety net is a prime reason for Michigan being a national laggard in the proportion of adults working.

Summarizing his findings on the topic, from our How Minnesota’s Tax, Spending and Social Policies Help It Achieve the Best Economy Among Great Lakes States report, Rick Haglund writes:

Many states have cut benefits to the poor and unemployed in the belief that these payments dissuade people from looking for paid work.

Minnesota takes a different view. It has created one of the strongest safety nets in the country, spending generously on benefits to help those who have lost jobs or been stricken by poverty get back on their feet.

That protective net has not trapped Minnesotans and turned them into a bunch of government-dependent slackers. Far from it.

Minnesota’s employment-to-population ratio of 67.2 percent in April was the fourth highest in the country, according to the latest data of the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project.

In Michigan, which has trimmed welfare and unemployment benefits, 56 percent of the adult population was working in April. Michigan ranked 41st in that measure.

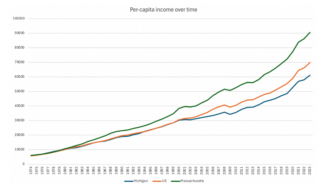

The data in Rick’s report is from 2014. In 2018 Michigan ranked 38th in the proportion of those 16 and older who worked. Minnesota ranked 3rd. If the same proportion of Michiganders worked as Minnesotans there would have been 725,000 more Michiganders working pre-pandemic. So much for a strong safety net leads to people preferring public benefits over working.

As Chairman Powell noted we should be serious about getting more Michigan adults into the workforce. My former colleague Patrick Cooney summarized our recommendations on how best to that:

The welfare reforms of the mid 90s were built on this central idea: cash supports would now be temporary, but the government would put more resources into ensuring people had the supports needed to put them on a path towards a family supporting wage.

Michigan’s safety net has failed on both of these fronts. Through policy changes and under investment in the state’s TANF system and unemployment insurance system, a large chunk of out of work Michiganders receive little to no cash assistance, nor do they receive the supports needed to obtain family-supporting work.

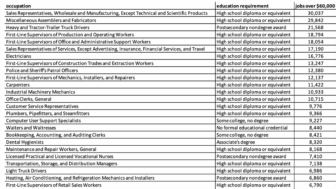

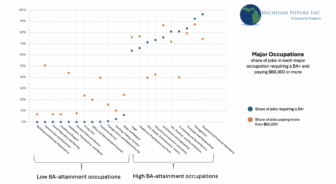

Our solution, as detailed in our Sharing prosperity with those not participating in the high-wage knowledge-based economy report, is built around two pillars:

The first pillar is to make it easy for those out of work to receive some form cash assistance. Cutting cash benefits both removes some semblance of stability for poor families, and removes the individual from the system of supports that can help put them on a path to family-supporting work. We should want Michiganders to be able to access benefits, both to provide desperately needed stability, but also to connect parents to valuable work-supports.

This means removing arbitrary lifetime limits on the receipt of cash assistance, increasing the generosity of cash benefits in both our welfare and unemployment insurance system, and using TANF dollars for core TANF purposes (cash assistance, work-related supports, and childcare assistance), rather than using the funds to plug holes elsewhere in the state budget.

Paired with a more generous safety net, the second pillar of our plan is to dramatically increase the supports individuals receive to get on the path towards family-supporting work. Our proposed approach is based on a 2014 House Budget Committee report by Paul Ryan titled Expanding Opportunity in America. In the report Ryan describes a system in which all supports would revolve around a central caseworker who would refer clients to a range of service providers, help them navigate a thicket of services and benefits, and recommend potential educational and job placement pathways.

This approach offers the flexibility to offer comprehensive and customizable supports to a range of individuals – from those facing multiple barriers to employment to those that are just temporarily out of a job – and has the potential to support individuals not just into a first job, but through multiple steps on the path to family supporting work. In a hypothetical case Ryan presents, a case manager guides a client from an entry-level retail job all the way through to college graduation and a full-time teaching position. Safety net benefits continue until the recipient is in stable good-paying employment.