It’s becoming clear that K-12 education is poised to be a central issue in the 2026 Michigan gubernatorial race, as it should be. On the 2024 NAEP reading exam (the National Assessment of Educational Progress, often called the Nation’s Report Card), just 24 percent of Michigan 4th graders scored at or above the NAEP proficiency threshold, and 45 percent of 4th graders scored below the “basic” threshold. Michigan’s 4th and 8th grade reading scores are now much lower than they were in the late 1990s, and have taken a precipitous dive since the onset of the pandemic.

These low scores are unacceptable, and must be fixed. Developing strong literacy skills early in a child’s education is critical for their long-term educational and life success, setting the strong foundation needed to build knowledge, think critically, and solve problems. Political leaders in Michigan are right to be concerned, and are right to emphasize the need for widespread adoption of evidence-based practices, like the science of reading, across all Michigan schools.

However, as important as early literacy is, it is also not enough. When we talk about Michigan’s broken education system, we need to be talking about much more than 4th grade reading scores.

Reframing the goal of Michigan’s education system

We have long argued that the goal of Michigan’s K-12 education system ought to be centered around postsecondary success. And given that most high wage jobs in today’s economy require a bachelor’s degree, we argue that the goal of Michigan’s K-12 schools should be to prepare all students to pursue and complete a bachelor’s degree if they so choose.

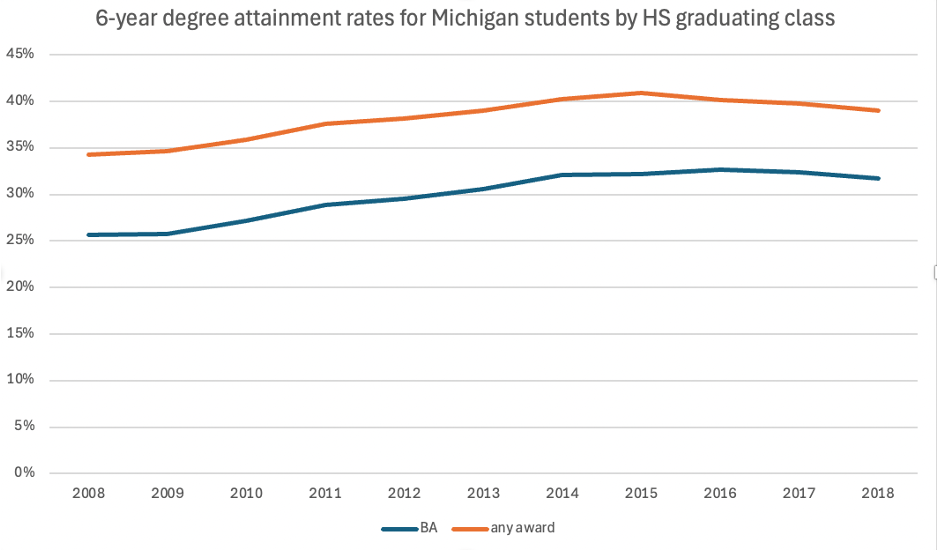

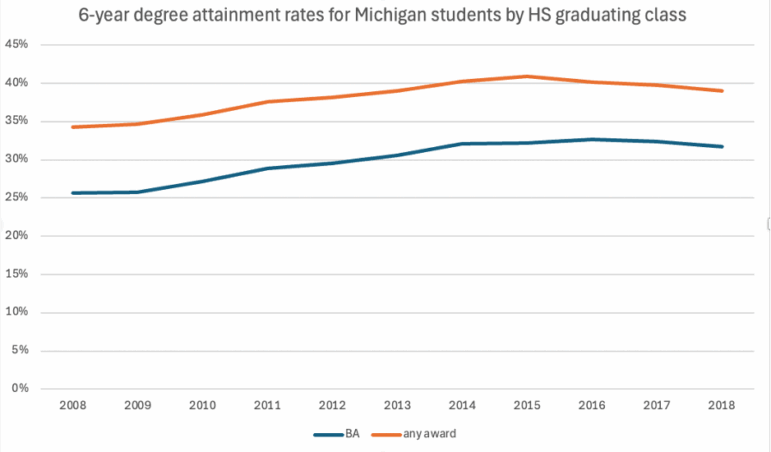

If we use postsecondary success as our ultimate measure of our K-12 system’s success – rather than 4th grade reading scores – Michigan is in no less of an educational crisis. After rising slowly from 2008 to 2014, the share of graduating Michigan high school students who complete a bachelor’s degree within six years of finishing high school has plateaued, and even declined slightly in recent years. Today, just 32% of graduating Michigan high school seniors will have a bachelor’s degree six years later, and less than 40% will have a degree or certificate of any kind.

One might reasonably argue that even if our ultimate goal is postsecondary success, political leaders are justified in placing our near-term focus on 4th grade reading scores, because surely 4th grade reading scores are an indicator of one’s future educational attainment. But the relationship between test scores and educational attainment is not as strong as one might think. A number of studies, leveraging the natural experiments created by charter school lotteries, find that schools that are very successful in raising test scores have little impact on postsecondary attainment, while some schools that have a large impact on postsecondary attainment have little impact on test scores. Another well-regarded study found the same effect with teachers – that those teachers who reliably improved their students’ “non-cognitive” skills were a different set from those teachers able to move test scores, and that the advancement of non-cognitive abilities ended up being a better predictor of long-run outcomes than improved test scores.

We see the same disconnect between test scores and postsecondary success when we look at NAEP scores among states, and those states’ overall levels of educational attainment. Test scores are an easy area to place our focus because they feel controllable. In the complex process that is a child’s education, test scores give us a concrete number, that we can try and improve upon and in doing so, we think, improve a child’s education and their life outcomes. However, for this to be true, test scores would need to be predictive of educational and career success. Improvements in test scores in one year would need to lead to improved test scores in future years, which would lead to greater levels of educational attainment.

The trouble is this smooth line of predictability doesn’t exist. Just look at Michigan. From the late 1990s to 2019, Michigan’s scores on the NAEP 4th grade reading exam were basically flat. Over that same period, however, Michigan’s scores on the 8th grade NAEP reading exam fluctuated dramatically. In other words, steady 4th grade scores did not lead to steady 8th grade scores. Add to this that the students who took the 8th grade reading NAEP in 2007, when Michigan’s scores bottomed out, went on to have the highest level of educational attainment of any educational cohort in the history of Michigan.

Some of the states we have heard mentioned over the years as potential models for Michigan’s K-12 education system include Indiana, Mississippi, Ohio, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Florida. But in each of these states you see the same disconnect between NAEP scores in 4th grade, NAEP scores in 8th grade, and ultimate levels of educational attainment. Indiana has long had 4th grade reading scores well above Michigan’s – yet the share of young adults in that state with a bachelor’s degree is three percentage points below Michigan’s. Mississippi’s 4th grade reading scores have been growing at a steady clip since the late 90s, but this progress has not been matched by their 8th grade test scores, which have been essentially flat. And for all that state’s growth in early reading, the share of young adults with a bachelor’s degree today is just 28% – roughly the level of educational attainment Michigan young adults had in 2010 (today we are at 37%).

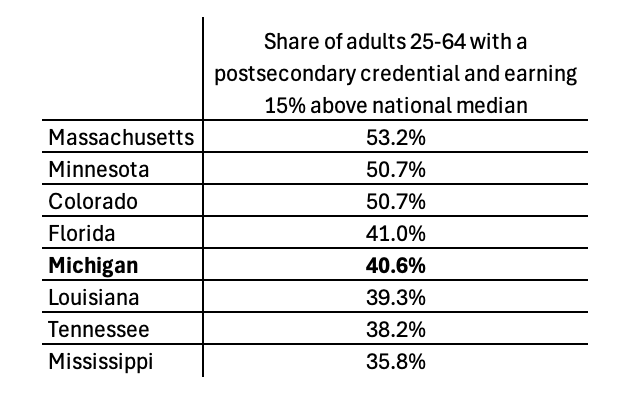

What states should Michigan be looking to as a model for its K-12 system? Again, we think the ultimate assessment of a school system ought to be the educational attainment and career success of the students in that system. And if we use this as our barometer, there are three states that stand out: Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Colorado.

The Lumina Foundation publishes a database called Credentials of Value, which measures the share of adults in every U.S. state that both have a postsecondary credential and earn a wage that is at least 15% more than the national median wage of those with no education beyond high school. Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Colorado are the only U.S. states where more than 50% of adults 25-64 meet both of those criteria. This is in large part because all three states have very high rates of BA attainment, and those with a bachelor’s degree or more are the most likely to be earning high wages. States like Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana, which are often mentioned as models for Michigan’s education system, all sit below 40%. A table of select states is below.

Focus less on the tests, more on what happens in the classroom

The reason that performance on standardized tests doesn’t line up neatly with educational attainment is that standardized tests measure only a small sliver of the capacities we need our students to develop if they are to be successful throughout their academic and professional lives. To be successful in college and career, students need to have a broad base of knowledge, be able to think critically, be able to communicate clearly, and be able to solve problems. On reading standardized tests, they are asked to read and demonstrate their understanding of arbitrary and decontextualized texts. One of these is not like the other.

It also turns out that if we want our kids to be better readers, we might do well to do less of what we might call literacy instruction. In 2001, President George W. Bush signed into law the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), which altered the shape of schooling in America. The law stated that by 2014, every student in the country would be proficient in math and reading. Much like 3rd grade reading laws that have emerged in state legislatures across the country over the past decade, NCLB stated a bold goal that was centered around students earning a “proficient” score on a high-stakes standardized test. Failure to make progress towards that goal would lead to consequences – principals and teachers would lose their jobs, failing schools would be shuttered. The theory of change felt sound: create a high standard, and then hold people accountable to achieving that standard.

The effect of the law on our schools and classrooms was that our students spent a lot more time on math and reading instruction, and a lot less time learning about science, social studies, literature, and the arts. But NCLB fell far short of its goals. In 2014 every student in the country was not proficient in math and reading – not by a long shot. In fact, between 2001 and 2014, student scores on the NAEP barely inched up. Over the same stretch, students’ scores on the SAT, ACT, and the international PISA exam either stagnated or declined.

Why did this happen? It turns out that doubling down on literacy skills in an effort to boost test scores may actually be counterproductive if we hope to produce proficient readers. We often think of reading as sounding out words, and of course that’s a big part of it. But in order to read effectively, and comprehend what you read, you not only have to be able to sound a word out, but also need to know what that word means, how it relates to all the other words in that sentence, what they all mean together, and how this piece of knowledge relates to everything else you know. In other words, your reading ability is directly related to your content knowledge.

In fact, many scholars cast doubt on the idea that there is a sort of “generalized” reading ability – rather, they suggest that all reading is context dependent. That is, if you know a good deal about what you’re reading about, you will read and comprehend more fluently than if you’re reading about a topic you have never encountered before. In one study, students were split into groups based on reading ability – one group of weak readers and one group of strong readers – and asked to read a passage about soccer. However, the weak readers all were quite knowledgeable about soccer, while the strong readers were not. The weak readers, able to neatly fit what they were reading into the web of knowledge already stored in their heads, performed better than the strong readers, who were attempting to build a new knowledge web while they read.

It may seem obvious that the more knowledge you have about a topic the better you will understand a passage about it, but these kinds of findings have dramatic implications for what students ought to be doing in our K-12 schools. If content knowledge is so important to reading fluency and reading comprehension, it means that when faced with low reading scores we perhaps ought to be spending less time on literacy instruction and more time on building students’ broad base of knowledge through science, social studies, literature, and the arts.

This has not, however, been our response so far. Faced with low proficiency scores on standardized tests, our students have been fed more drills and more “literacy instruction,” and less knowledge about the world. The worry is that a single-minded focus on 3rd grade reading scores as the sole measure of our education system’s success would only accelerate this trend, pushing more and more “literacy” instruction into our K-12 schools, which would yield little to no improvement in student learning, and the longer-run outcomes we ultimately care about.

What should we be focusing on in K-12?

The case I’m trying to make in all that’s outlined above is that we need to be really careful about building our education system around a single test in a single year, and the ways in which such a single-minded focus can negatively impact the learning experiences of Michigan children. If we place all our focus on the narrow band of educational skills measured by standardized tests – which may end up being counterproductive in actually improving even that narrow band of skills – we may miss all of the rest of what we should be developing in kids: the ability to communicate clearly, think critically, and build a broad base of knowledge that will help them to read, solve problems, and ask the right questions.

Indeed, it is this set of “other” skills, mindsets, and capacities that our children will need to be successful in college and career, and where we should be placing our focus. Engaging content – through which students can build a broad base of knowledge – should sit at the center of our children’s education. Without a broad base of knowledge, students will struggle to comprehend what they read, think critically about information they consume, or solve complex problems. Students should develop a deep understanding of math and science concepts, rather than surface-level “rules” for solving problems. And the ability to write clearly – to make arguments, and back them up with evidence – should be a skill consistently reinforced throughout our children’s education. If we do all these things, our students will be adequately prepared for college and career. Their scores on 4th grade reading exams will improve as well, though that is a secondary concern.