Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing a series of posts about the importance of educational attainment – both to our statewide economy and to individual economic mobility and prosperity – and how we should be designing our K-16 education system to increase the number of Michiganders who attain bachelor’s degrees.

This second post outlines the importance of bachelor’s degree attainment to an individual’s economic well-being, and to racial equity and economic mobility goals. See the link to the previous post below

Part 1: The importance of BA attainment to a state or region’s economic development

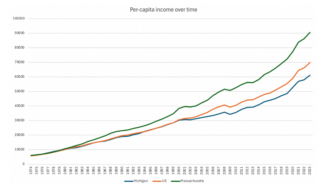

In my last post, I discussed the importance of educational attainment to the macroeconomy. Simply put, if one knows the level of educational attainment in a state or metro region – as measured by the share of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher – they can accurately gauge the economic health of that state or region, as measured by per-capita income.

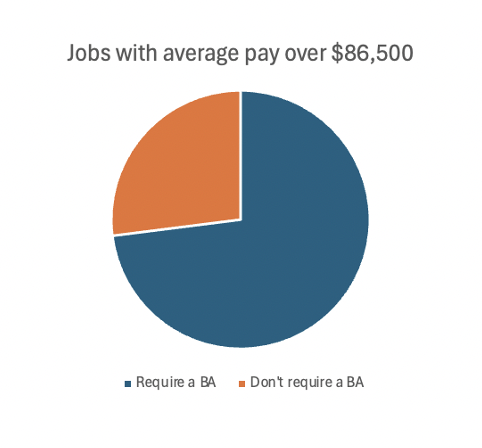

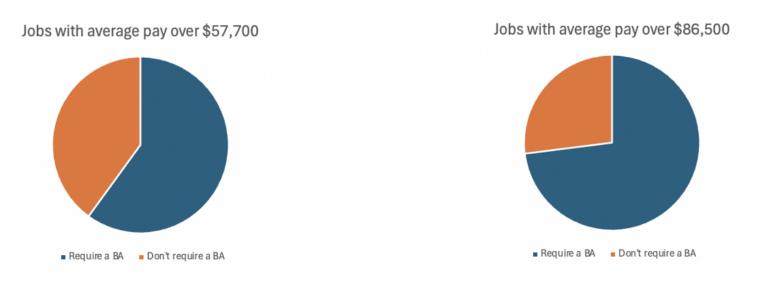

But, more importantly, educational attainment also matters a great deal at the individual level. Despite media narratives that often suggest otherwise, a four-year college degree remains an individual’s surest route to a middle-class income. In our analysis of labor market data, we set a “middle-class” income threshold at $57,700: this is the annual income a worker would need to support a family of three at the lower end of a middle-class lifestyle. 60 percent of jobs in the U.S. economy that pay enough to clear this threshold require a bachelor’s degree or more. If we set the threshold at $86,500, our threshold for “upper middle-class,” the share of jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher jumps to 73 percent.

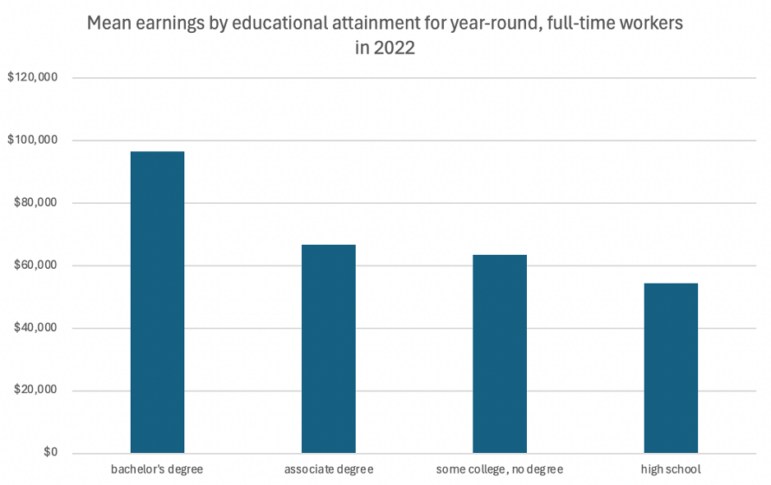

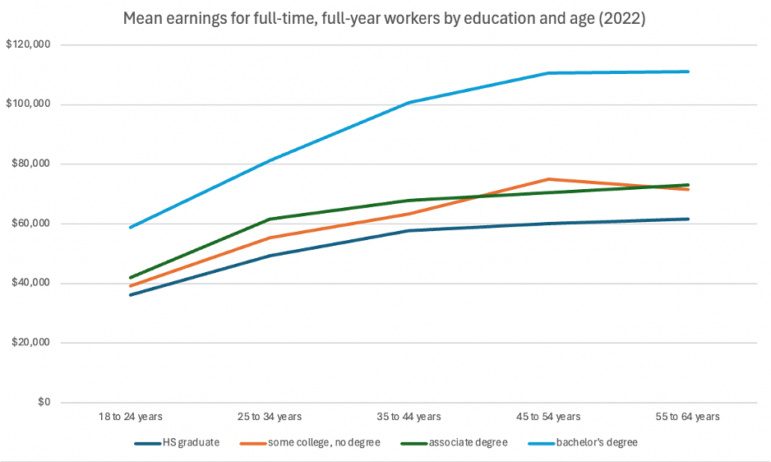

Indeed, the so-called “wage premium” associated with earning a four-year college degree is not only large, but it also grows substantially throughout one’s career. If we take all full-year, full-time workers, the average bachelor’s degree holder (this analysis is limited to bachelor’s degree holders, and does not include those with graduate degrees, whose earnings are even higher) earned roughly $96,500 in 2022. This is $42,000 more than the average earnings for a full-year, full-time worker with no education beyond high school, $33,000 more than a worker with some college, but no degree, and $29,800 more than a worker with an associate degree. In short, the college wage premium is really large.

But also noteworthy is the extent to which the wage premium grows throughout one’s career. The chart below shows the average earnings of full-time, full-year workers by age and educational attainment, in 2022. The gap is slightly smaller, though still substantial, for workers early in their careers ($22,700, $19,700, and $17,030 respectively), but is massive by mid/late career: for those between 55 and 59, the gaps were $52,900, $41,200, and $38,900.

Author’s analysis of 2022 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement

In short, the idea that a four-year degree is not worth the money, an idea that has gained considerable currency in the news media over the past few years, is preposterous. The earnings gap between those with and without a four-year degree is large and grows considerably throughout one’s career.

The most dependable route to economic mobility

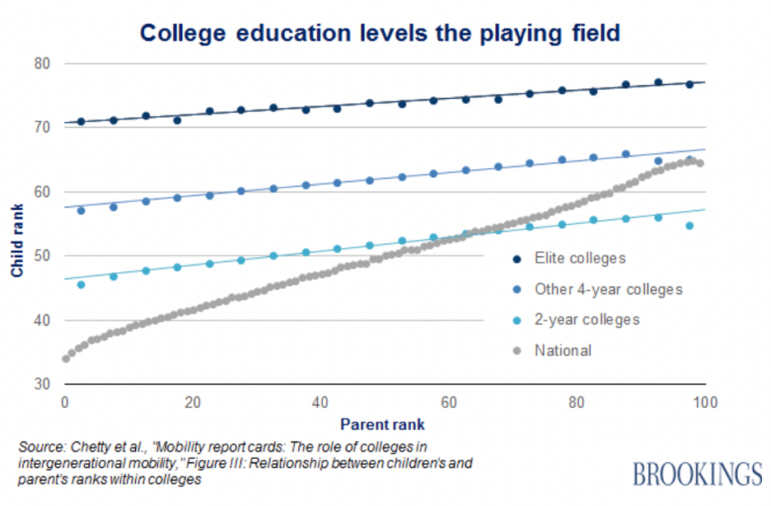

A college degree is even more important for those growing up in non-affluent households, as earning a college degree remains the most dependable route to economic mobility. Harvard economist Raj Chetty, and his team at Opportunity Insights, used detailed tax records and administrative data from colleges and universities to track adult earnings based on an individual’s parents’ income, their college attainment, and the selectivity of the college they graduated from. What we see from this data (chart copied below) is that, in general, the income of one’s parents is highly predictive of an individual’s income as an adult: children raised in non-affluent households tend to remain non-affluent as adults. However, we also see that graduating from college, and especially graduating from a selective college, disrupts this general pattern. If you earn a college degree, parental income no longer determines one’s fate. On average, an individual whose parental income fell in the bottom quintile is expected to have adult income in the 30th to 40th percentile. However, if that individual graduates from a four-year college, their income as an adult is expected to rise to around the 60th percentile; if they graduate from an elite school, over the 70th percentile. Earning a four-year college degree completely alters one’s economic trajectory.

Chart found in piece by Richard Reeves and Eleanor Strauss, Brookings Institution (https://www.brookings.edu/articles/raj-chetty-in-14-charts-big-findings-on-opportunity-and-mobility-we-should-know/)

This is all worth dwelling on because in recent years there has emerged an anti-college backlash, driven by concerns over the high price of college, and stories about young, underemployed students crushed by student loan debt. In one high-profile piece in the New York Times Magazine, Paul Tough cited research showing that while college graduates enjoyed a wage premium, the high cost of college erased any wealth premium a college graduate might receive, because they had to use those higher wages to pay down student loan debt. However, research Tough cited was based on the faulty assumption that the college wage premium does not grow throughout one’s adult life (as we previously noted, it more than doubles throughout ones career). When corrected, one finds college graduates enjoy not only a large wage premium, but also a large wealth premium, not to mention a host of non-pecuniary advantages. In fact, recent data from the federal reserve found the wealth gap (measuring the total value of the assets one owns) between those with and without a college degree is growing even faster than the income gap. In 1989 the total wealth of those with a college degree was roughly $6 trillion higher than the total wealth of those with no education beyond high school. Today, this gap is $95 trillion.

What about the future?

Still, despite this mountain of evidence demonstrating the economic value of a four-year degree, there will be some who continue to question its value. Sure, a college education used to be worth it, they will say, but the economy is changing. Today, it’s all about skills and stackable credentials. The four-year degree is a thing of the past.

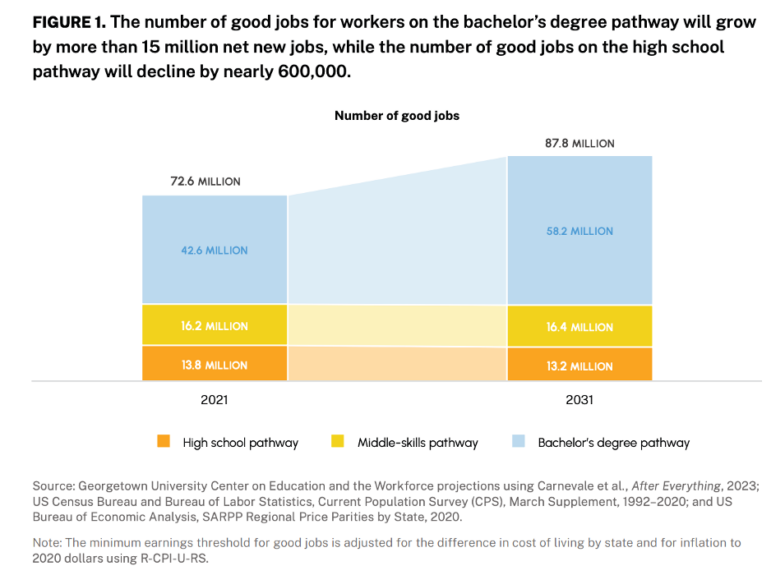

Wrong again. According to a new report from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, between 2021 and 2031 there will have been an additional 15 million net “good” jobs added to the economy, defined as defined as those that pay a median of $74,000 to workers ages 25-44, and $91,000 to workers ages 45-64. The number of good jobs requiring no education beyond high school will decline by 600,000, while the number of good jobs requiring a sub-BA credential will increase by 200,000. The number of new good jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher? 15.6 million.

In 2031 there are projected to be nearly 88 million good jobs, and roughly 58 million (two out of every three good jobs) will require a four-year degree.

Chart found in The Future of Good Jobs: Projections through 2031, by Jeff Strohl, Artem Gulish, and Catherine Morris

Simply put, for an individual, completing a bachelor’s degree is the most dependable route to the middle-class – today, and for the foreseeable future. And for society, eliminating educational attainment gaps by race and income is the surest way – and perhaps the only dependable way – to achieve goals around economic equity and mobility.

In my next post I’ll take a hard look at how we’re doing at achieving those goals, by looking at educational attainment rates and college completion rates.