In the postsecondary education landscape, short-term credentials hold a certain allure. In conversations around education and the future of work, certificates and credentials are often viewed as the way forward. To succeed in the future economy, the argument goes, some postsecondary education is needed, but it need not be a four-year degree. This argument holds that there are numerous good paying jobs out there for those without a four-year degree, but with an “industry-valued credential.”

People want credentials to work. There is a demand for higher education alternatives that are lower cost, or perhaps more accessible to those that did not receive a high-quality K-12 education. There is a demand for short-term pathways for mid-career workers to retool without taking years away from the workforce.

The trouble is, it is not at all clear that the vast majority of short-term credentials deliver much value to their holder. Despite the many state and business leaders touting the promise of short-term credentials, and the pathways to “good jobs” that don’t require a four-year degree, the data simply does not support short-term credentials as a viable strategy to promote economic mobility, or achieve racial or socioeconomic equity in educational or labor market outcomes.

A 2021 report from New America reviewed the existing literature on the value of short-term credentials, and the picture it paints is bleak. The consensus, based on available research, is that these credentials, on average, do show some positive labor market value, but the return is low, and fades out quickly. And even these modest, short-term gains come with a number of caveats. While some programs lead to a temporary earnings boost, “…many others show no – or even negative – results.” One recent report found that half of those who completed a very short-term certificate were earning “poverty level wages” and that roughly 40% were not employed. In addition, many of the studies analyzing the short-term credential landscape also fail to take into account the cost of attendance, including loans. So even if we do see a modest pay bump from certain programs, it’s not clear this bump is enough to compensate for program costs.

It should be noted that these uninspiring data on the returns to sub-BA credentials are only for public institutions – state data systems often fail to capture student-level information from for-profit institutions. This is a problem because all available evidence suggests outcomes at for-profit institutions are much worse than at public institutions, yielding a more troubling picture of the sub-BA landscape. Research has shown that credentials from these institutions carry lower labor market value than credentials from other institutions, and, as we’ve written previously, the most students who default on their student loans are those that attended a for-profit institution, the result of both higher costs and lower labor market value of their credential.

For proponents of short-term credentials, it’s often imagined that workers will “stack” these credentials over their careers, as they gain more and more skills. In practice, this doesn’t seem to happen. Research suggests just two to four percent of the workforce have what we would call stackable credentials, and that the majority are owned by those who already have a bachelor’s or associate degree. In other words, they already have a broad base of knowledge and skills, and they are simply layering new, discrete skills they want to learn on top of that foundation. The research suggests you can’t skip this broad foundation and go straight to the specific, technical skills.

What makes all of this worse is that there are clear racial and socioeconomic divisions in who does and does not pursue short-term credentials. White students are far more likely to pursue a four-year degree; Black and Hispanic students far more likely to pursue a short-term credential. Certificates make up just one in five of the credentials completed by white students, but one in three for Black and Hispanic students. Far from a tool to promote equity, a Community College Research Center report notes that because high-income students are more likely to pursue a bachelor’s degree, and receive the dependable benefits of this degree in the labor market, and low-income students are more likely to pursue a short-term credential, with its modest, uneven, and temporary returns, “growth in certificates will lead to a further stratification of the higher education,” and lock in, rather than combat, economic inequality.

Not all sub-BA credentials carry low labor market value. There is some evidence that gaining an occupational license, for instance, can boost employment and earnings outcomes. But here again, the majority of those with an occupational license (roughly 60%) already have a BA, and are simply adding a new qualification atop their educational foundation.

And while the data is still a bit uneven, there is also some evidence that within the sub baccalaureate space, associate degrees and longer-term credentials have more dependable labor market returns than short-term credentials. The rule of thumb seems to be that the longer the program, the more likely you are to have durable, dependable returns. To quote the New America report, “Education and training done well are hard work, and take time. Shortcuts to long-term prosperity are usually too good to be true.”

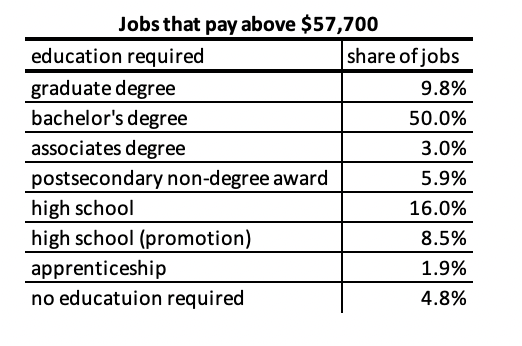

But it’s also important to note that the majority of pathways to good paying jobs that don’t require a bachelor’s degree don’t go through any type of postsecondary institution at all. The chart below shows Bureau of Labor Statistics data for the education or experience required for jobs that pay more than $57,700 annually, our threshold for a lower-middle-class income for a family of three. Just three percent of good paying jobs require an associates degree, and another roughly 6% require some other kind of sub-BA credential. Meanwhile, 16% of good paying jobs require nothing more than a high school diploma, with another 8.5% requiring a high school diploma and a promotion on the job.

What we see in this data matches the findings of some qualitative research we took on a few years ago, in collaboration with the Ralph C. Wilson Jr. Foundation. In that study, we conducted focus groups composed of individuals who earned above a middle-income threshold but did not have a bachelor’s degree. What we found was that the majority of these individuals reached their current salary through training or advancement opportunities at their current job and were internally promoted. A relative minority gained their middle-income status through a sub-BA training program.

In other words, our analysis of the labor market urges caution before pushing more and more young people into short-term credential pathways, because there may not be as many good paying jobs as we might think waiting for them on the other side.

Faced with this picture of the sub-BA landscape, one clear avenue for action is to develop data systems that equip prospective students with much better data about which programs do and do not pay off in the labor market. Quoting the New America report again, “If students and policymakers are to make wise decisions about attending and financing postsecondary education, it is essential to learn more about which programs carry labor-market value, from which institutions, and for which students.”