There’s a lot of attention right now on the state’s population. We’re not attracting and retaining enough young people, our workforce is aging, and our economy is sputtering. In response to these challenges, the governor has formed the Growing Michigan Together Council, primarily tasked with identifying a set of recommendations for how to grow the state’s population.

Seeing as how young people, and young people with a college degree in particular, are by far the most mobile segment of society, any effort to grow the state’s population ought to be squarely centered on this group. Indeed, a recent poll commissioned by the Detroit Regional Chamber and Business Leaders for Michigan focused solely on the preferences of 18 – 29 year-olds here in Michigan, and what the state needed to do to keep them here.

But to inform the state’s policy response to stagnant growth, it’s also worth figuring out where the young people who have left Michigan have gone, to better understand the characteristics of the places they have gone to. Figuring out where young folks bred in Michigan are casting off to once they reach adulthood can help inform efforts to turn Michigan into the kind of place they might want to stay, and the kind of place that might attract young people from the rest of the country.

The Census Bureau, in partnership with Harvard’s Opportunity Insights and MIT’s Policy Impacts, recently created a tool that can offer some clues as to where young mobile Michiganders are settling in young adulthood. Called Migration Patterns, the tool uses Census and tax data to identify where young people were living at the age of 16 (presumably in the place where they grew up) and where they are living at 26, in young adulthood. The data is presented by commuting zones, collections of counties centered around a primary employment center. For each commuting zone, we can see what share of young adults living there grew up there, and, for those that did not grow up there, where they came from. And for those that left a particular commuting zone, we can see where they ended up. This data covers the 1984 to 1992 birth cohorts, who would have reached age 26 between 2010 and 2018, so is looking at pre-pandemic migration patterns, though we have no reason to think there has been much change in the post-pandemic period.

The data can also be cut by race and by parental income, offering a sense for how migration patterns vary by individual characteristics. While the data is not cut by educational attainment, because parental income is (unfortunately) highly correlated with college attainment, we can use parental income as a crude proxy for education.

This will be the first in a series of posts exploring this data, which yield a number of findings that can help inform the state’s efforts to attract and retain young talent.

Where are Detroiters going?

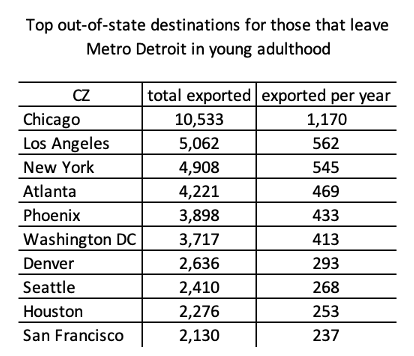

Let’s first look at Detroit, the largest metro region in the state. Included in the Detroit commuting zone are Genesee, Lapeer, Livingston, Macomb, Oakland, Sanilac, Shiawassee, St. Clair, Wayne, and Washtenaw counties. 75% of young adults who grew up in the metro Detroit area remain in metro Detroit in young adulthood. Another roughly 5% moved to another part of the state, and 20% left the state. Where did they go? The leading CZs are listed in the table below. The data captures nine birth cohorts, so here we the total number of young people exported to each commuting zone over those nine cohorts, and the average exported to that metro area each year. Chicago, as we might imagine, is by far the largest magnet for young adults from Detroit, followed by LA, New York, and Atlanta.

If we look at young adults who grew up in a home with a parental income in the top quintile – who are more mobile and more likely to be college educated than the general population – the picture changes slightly. The top destinations remain largely the same, but we lose many more of this cohort. While 75% of all young adults who grew up in metro Detroit remained there as young adults, just 66% of high-income young adults did the same. Another roughly 6% moved somewhere else in Michigan, and 27% moved out of state, largely to Chicago, New York, LA, Washington D.C., and Denver.

Black young adults who grew up in Detroit are more likely to remain in Detroit (81%). Those that move out of state (16%) are heading for Atlanta, Phoenix, Chicago, and Houston. Black young adults who grew up in high-income homes are, again, slightly less likely to remain in Detroit (73%), and those that move out of state (25%) again head to Atlanta, Chicago, D.C., New York, and LA.

The diaspora of young Black Detroiters to Atlanta is particularly noteworthy. If we look at young Black adults who currently live in Atlanta, were raised in a high-income household, and came from out of state, native Detroiters are overly represented, serving as the third largest source of out-of-state high-income young adults, behind D.C. and New York.

In a future post we’ll take a deep look at the migration of Michigan’s Black young adults, and the regions they are landing in.

What about Grand Rapids?

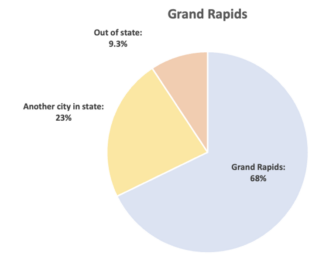

The picture in Grand Rapids is pretty similar to Detroit’s, though a slightly larger share of those that grow up in Grand Rapids opt for another Michigan city in young adulthood, rather than moving out of state (the Grand Rapids commuting zone includes Allegan, Ionia, Kent, Montcalm, Muskegon, Newaygo, Oceana, and Ottawa counties). For the overall population 71% of those that grow up in Grand Rapids stay there as young adults, with another 10% landing in another Michigan region, and 19% heading out of state, with Detroit and Kalamazoo as the leading Michigan destinations, and Chicago, LA, Denver, and Phoenix the leading destinations nationally. For those growing up in high income households, 62% stay in Grand Rapids, with 11% heading to another Michigan region and 27% moving out of state. Detroit, Kalamazoo, Chicago, Denver, and LA are again the top destinations.

It’s not really about retaining – it’s about attracting

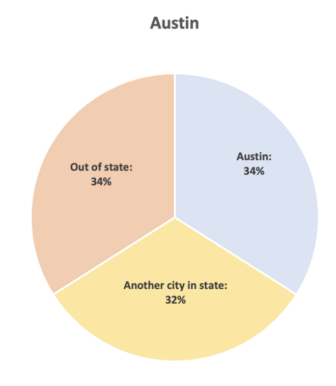

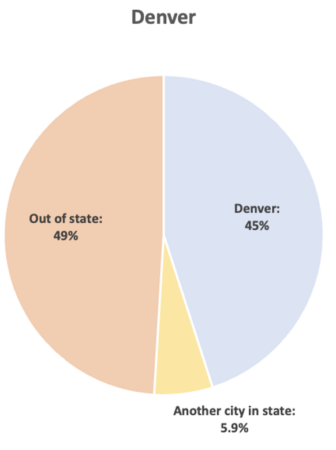

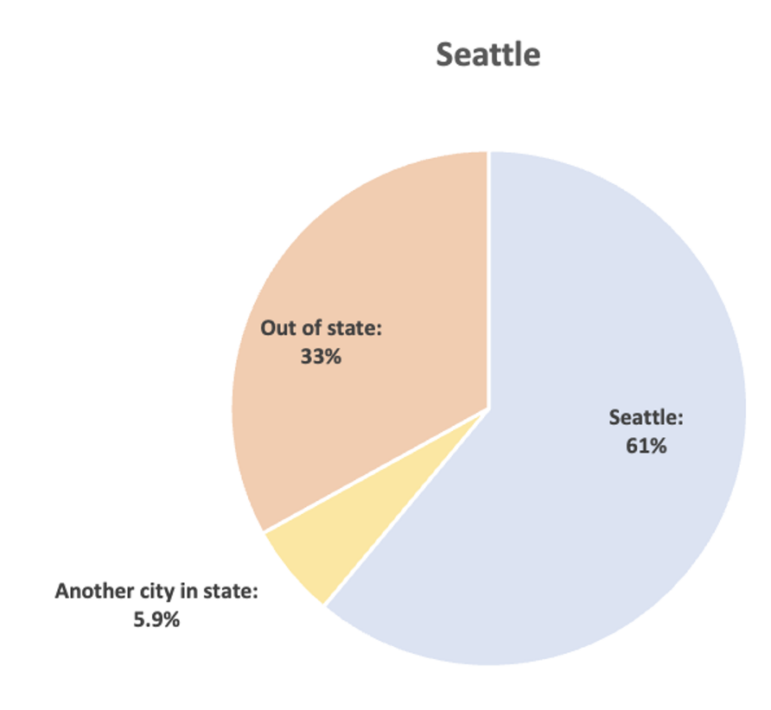

One thing that’s really important to note is that our major metros actually do a pretty good job of retaining young people. 75% of those who grew up in metro Detroit remained here as young adults, 71% in metro Grand Rapids. These figures are comparable to those of new talent magnet cities like Denver (71%), Austin (69%), or Seattle (75%). As previously mentioned, if we look at young adults raised in high income households, the share that stick around declines in each region, but our retention rate remains quite similar to major talent magnets.

Where the difference lies between our region and national talent magnets is how many young people from other parts of the country move here. We can get some sense of where our major metros stand on this measure by looking at the composition of young adults in our metros today, and where those young adults came from. In our nation’s talent magnets, a large share of young adults living in those regions did not grow up there: 48% of young adults living in Denver moved there from outside of Denver; 56% of young Austinites came from elsewhere; and 37% of young adults in Seattle did not grow up in Seattle. In Detroit, just 13% of young adults came from elsewhere.

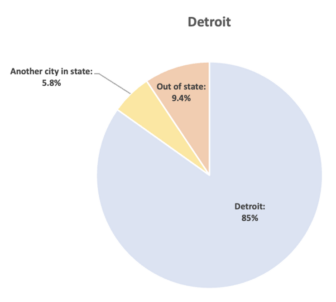

In the pie graphs below this analysis is restricted to those young adults raised in high-income households, given their higher rates of mobility and educational attainment. The pies are broken down by the share of young adults in a particular region who grew up in that region, came from another region in the state, or came from out of state. As you can see, in the talent magnet regions (Denver, Austin, and Seattle), more than 30% of high-income young adults came from out of state; in Detroit and Grand Rapids it’s less than 10%.

A decent share of high-income young adults in Grand Rapids are transplants, but are largely from other Michigan regions (23%) rather than out of state (9.3%) So while Grand Rapids may not yet be a talent magnet for young professionals elsewhere in the country, it may be an emerging talent magnet for native Michiganders.

Denver vs. Detroit: 40 to 4

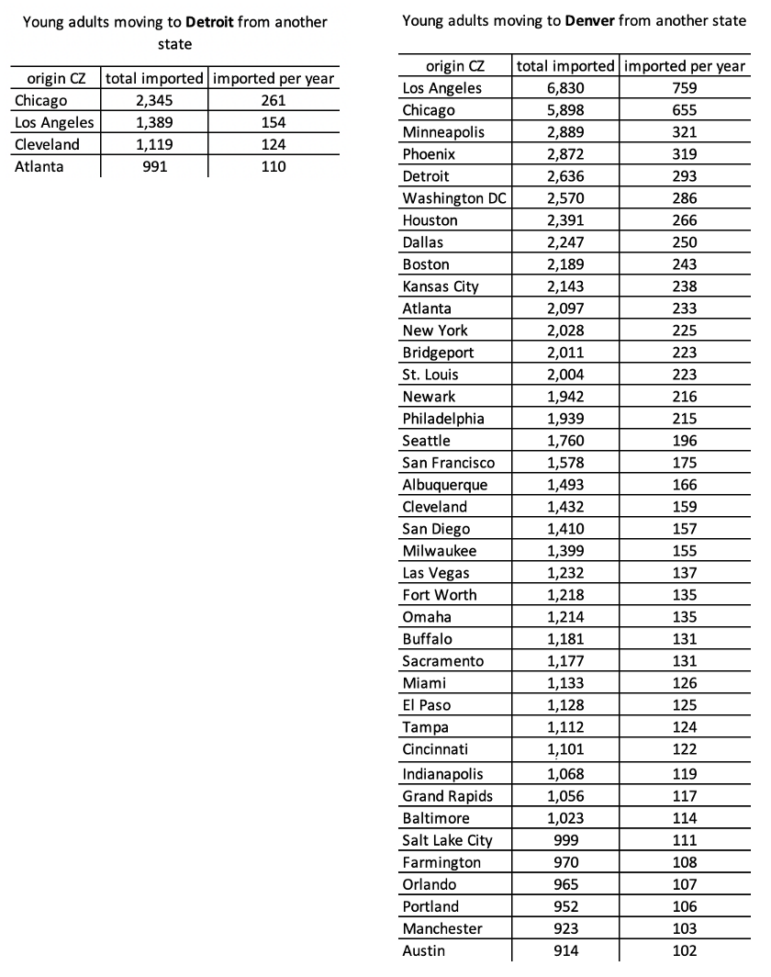

To put a finer point on this analysis, and to show the gap that currently exists between a talent-magnet region like Denver and Detroit, we can look at the numbers out-state young adults landing in each region, and where those folks came from. The tables below show the number of out-of-state young adults who moved to Detroit or Denver, over this nine-year period. I’ve included all origin commuting zones that sent at least 900 young people to these destination cities (or an average of 100 per year).

The findings are stark. As one can see, there are only four out-of-state metros in the country that sent at least 900 young people to metro Detroit over this period: Chicago, LA, Cleveland, and Atlanta.

Metro Denver, which has a smaller population that metro Detroit, received at least 900 young people from 40 out-of-state metro regions – ten times Detroit’s figure.This is what we mean by a talent magnet – a place that attracts young people not just from anywhere in the country, and anywhere in the world.

What can we learn?

So, what can we learn from this data that can help inform our efforts to attract young talent to Michigan? This data largely confirms what we already know, and have written about often in this space: young people, and highly-educated young people in particular, are flocking to major metropolitan areas anchored by vibrant central cities. In particular, these young people are seeking out central cities that feature dense, walkable, activity-rich neighborhoods.

The core distinction of today’s talent magnets is the presence of some kind of “scene” – a creative scene, an arts scene, a music scene, an outdoor recreation scene, a tech scene. While you can’t really create a scene through public policy, the right public policies can create the foundation for that scene, by helping to create places where young people want to be.

Last year we proposed the Neighborhood Talent Concentration Initiative, which called for the creation of a large fund that would award grants to Michigan cities that developed neighborhood/district wide plans designed to create dense, walkable, activity-rich places, with a focus on attracting young people. This is still one of the strongest levers available for turning Michigan’s central cities into talent attractors.

It is also worth noting what young adults are not moving for. First, they are not moving for low-cost housing. In nearly every article outlining Michigan’s population challenges, and what the state can do to fix it, lowering housing costs comes up as a potential lever. However, the places young people are moving to – Chicago, LA, New York, Atlanta, Denver – are not low-cost locales. According to the most recent Census data, median rent on a two-bedroom apartment in Denver is over $1,900, roughly $700 more than median rent in Grand Rapids and $900 more than in Detroit. Yes, housing prices are important, and become even more so as young adults get older and start families. But there is also a reason that millions of young people continue to pay really high prices for really small apartments in New York and LA every year – place matters.

Second, these young adults are not moving for ajob, or at least not for a particular job. Economic development discussions in Michigan center primarily around manufacturing employment, and “winning” projects and jobs, through tax breaks and incentives. The theory is that if we bring enough jobs to Michigan, the people will follow.

But this has it backwards. Young people aren’t tracking economic development reports to see which city won this or that manufacturing plant, and deciding where to move based on this information. They are moving to particular cities because they are great cities, with thriving economies. To the extent young people are moving for a job, they are not moving for any one job, but for a whole host of potential economic opportunities that may be available in a city’s economic ecosystem. And in today’s economy, that thriving economic ecosystem will be driven primarily by knowledge work – done in offices and research labs and hospitals and universities. All of the places that young Michiganders are moving to – whether they are knowledge workers or not – are heavily concentrated in knowledge industries. Indeed, you cannot have a thriving economy without high concentrations of knowledge work. So, if these young people are moving for economic opportunity, it is likely because they see a thriving economic ecosystem – they are not moving, necessarily, for any one job, but because they see the possibility of a range of potential careers and areas for growth in a particular place.

How do we create a thriving economic ecosystem, built around the knowledge economy? By focusing on place. In today’s knowledge economy, talent attracts capital, and quality of place attracts talent. Put simply, if we want to attract more young people from across the country, we need to focus on building great cities – dense, walkable, activity-rich places, where people want to be.