This post summarizes a short report we wrote on the benefit cliff in Michigan, which can be found here: Mapping and Addressing Benefit Cliffs in Michigan

In early 2023, Senator Kristen McDonald-Rivet established a working group to explore the so-called “benefit cliff,” and its impact on Michigan families. Most public benefits (SNAP benefits, housing assistance, cash assistance) are “means tested,” meaning as employment income increases, the level of public assistance a household receives declines. A “cliff” occurs when the next dollar of income earned by a household actually reduces a household’s overall resources from employment income and public assistance combined. In the case of a true cliff, a household is made worse off, or no better off,through increased income from work. If cliffs are present in the benefits schedule, they could disincentivize work and lead to greater household financial instability. The goal of the workgroup was to identify these cliffs, as well as policies to mitigate them.

Through biweekly meetings over six months, and several analyses conducted by Michigan Future (MFI eventually took over coordination of the working group), we arrived at a number of core findings, outlined below, that can not only guide our efforts to address the so-called cliff, but also help us build a stronger safety net overall, that better supports working families. These findings are outlined in brief below, and you can find a link to the full report here.

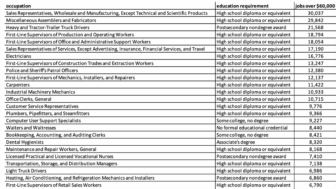

Most public benefit programs have very limited reach. It’s important to understand when we talk about public benefits just how few programs actually reach a large share of low-income households. In analyzing how Michigan’s benefit system interacts with household income, we looked at most major public benefits programs: food assistance (FAP in Michigan; SNAP nationally); cash assistance (FIP in Michigan; TANF nationally); health insurance (Healthy Michigan, Medicaid); housing assistance (public housing; section 8 vouchers); childcare assistance; the earned income tax credit and state earned income tax credit; and the child tax credit. Of these programs, the only ones that reach a high percentage of low-income Michigan households are SNAP, Medicaid, and refundable tax credits (EITC and child tax credit). Housing vouchers reach only a quarter of eligible families; only 11% of poor families in Michigan receive cash assistance; and just an estimated six percent of children eligible for a childcare subsidy receive one. So in thinking about how employment income interacts with the public benefits system, we did not include these programs with low utilization rates, and instead focused only on those programs that reach the vast majority of low- and moderate-income Michigan households.

True “cliffs” largely don’t exist, but households do experience a steep marginal tax on benefits. A true cliff is when a decline in public assistance resulting from additional employment earnings leads to a net decline in household resources. By and large, this kind of cliff does not exist. Indeed, most public assistance programs are specifically designed so that households do not experience a decline in total resources from additional employment earnings.

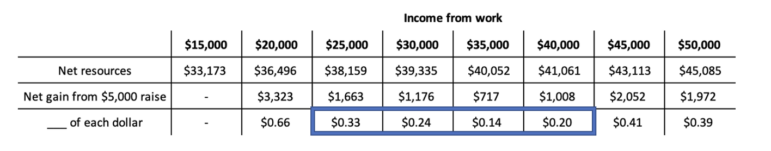

However, many households with children receiving public benefits still experience a steep “marginal tax” on their net resources resulting from additional employment income, which can lead to financial instability and, potentially, a disincentive to earn more income. This is especially true for households receiving assistance from multiple programs, which all may decline simultaneously as income increases.It’s important to emphasize that because much of our safety net is designed to support children (e.g., SNAP allocations and EITC refunds are larger for households with children), it is workers with children who also see the highest taxes on their benefits as they earn more.

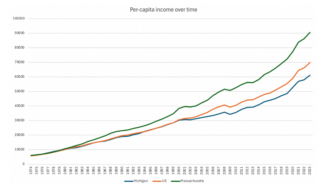

In particular, we found that a household with children earning between $20,000 and $40,000 from work has relatively static net household resources (income from work plus public assistance) over that entire income range (see chart below).

The rules for the largest means-tested programs are set federally, so most of the meaningful levers for alleviating this high tax on benefits would need to be pursued in Washington, not Lansing. States have little control over the structure of most public benefit programs. For example, benefit levels and income eligibility determinations for the largest public benefit program, SNAP, are determined by federal policy, and monitored by federal agencies. There is considerable state flexibility in the TANF program, but Michigan has used the autonomy afforded under TANF to dramatically restrict cash assistance and use TANF dollars to fill gaps elsewhere in the state budget. The state could theoretically use these dollars to structure programs that provide cash to households experiencing benefit taxes in other programs, though this would be a dramatic departure from current uses.

There are some other small changes states can make around the edges to make benefits easier to access (e.g., raising asset limits, enabling cross-program eligibility), though Michigan has already implemented many leading practices in this area.

Though state policymakers cannot alter the design of most means-tested programs, state leaders should develop a federal reform agenda to ease high benefit taxes. In particular, an expansion and/or redesign of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit or SNAP program could significantly reduce the benefit tax faced by working households.

The strongest lever available to states to combat high benefit taxes is to expand their state EITC. The most important thing states can do to boost the incomes of households hit by high benefit taxes is to implement or expand a state earned income tax credit, which Michigan recently did. Michigan’s expansion of its state EITC, from 6% to 30% of the federal credit, places Michigan near the top of all states in the size of its state EITC.

Because working households with children face the highest benefit taxes, and those with young children must incur the additional cost of childcare, Michigan Future recently proposed a second refundable tax credit, the Working Parents Tax Credit (WPTC), to help combat benefit taxes and alleviate the cost of childcare. The WPTC would provide all EITC-eligible households with young children and employment earnings of at least $10,000 with a per child refundable tax credit worth $5,000 for each child under three, and $2,500 for each child older than three but younger than six.

Improving access to public benefits is part of the solution. The workgroup eventually held a series of meetings on ways to improve access to public benefits in Michigan. For most public benefit programs, there are thousands of eligible households who fail to receive benefits, either because of lack of knowledge of the program’s existence, or obstacles encountered in the application process. While reforms to improve access do not alter the means-tested design of the system, they would help achieve the goal of enhancing the financial stability of Michigan households, by ensuring greater access to those households eligible for benefits. We heard presentations from Civilla, the non-profit design studio that partnered with MDHHS on a number of human-centered design initiatives to remove obstacles from the benefits system; from Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson about the work she has led to dramatically improve customer service in her department; and from Propel, an organization that builds technology tools to help families manage their safety-net benefits. Much can be learned from these and other efforts around how we make interacting with our public benefits systems as seamless as possible.

For questions/comments on this or any other post written by me, please feel free to e-mail me at patrick@michiganfuture.org