Most discussions about economic development in Michigan are pretty narrowly focused. How many jobs did we “create?” What companies did we “attract”, or retain? Manufacturing jobs receive the lion’s share of attention, and it’s generally understood that in order to create or retain these manufacturing jobs, we need to offer firms incentives, usually in the form of tax abatements, land assembly, or direct subsidies. This seems to be the calculus of economic development – how many jobs, for how much money?

The trouble is, this approach to economic development ignores vast swaths of the modern economy, including those industries that are the true drivers of prosperity in the 21st century. This means that, at best, our dominant approach to economic development is short-sighted; at worst it’s counterproductive.

What’s the alternative? The data from the past two decades makes clear that the core driver of economic development in states and regions is not factories or firms, but talent. The most consistent predictor of a city, region, or state’s economic success in today’s economy is the share of its adults – and in particular young adults – with a four-year degree. Where young talent goes, high-wage, knowledge-based enterprises follow, expand, and are created. In the words of Harvard economist Ed Glaeser, “the right economic development strategy at the local level is to attract and train smart people and then more or less get out of their way.”

In this post, I’ll explore the data showing the connection between educational attainment and per-capita income at the state level. In future posts, I’ll dig into the implications of this connection for economic development policy in Michigan.

Educational attainment and per-capita income

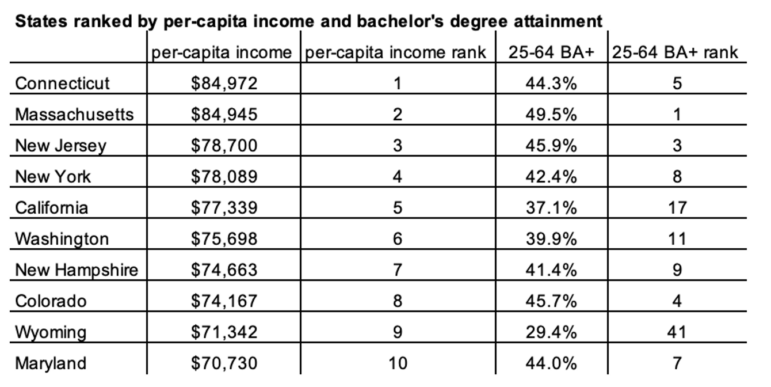

The connection between educational attainment and per-capita income at the state and local level is remarkable. The table below shows the top ten states ranked by per-capita income, as well as their rank by the share of 25-64 year olds with a bachelor’s degree or more.

Each state in the top ten in per-capita income is in the top twenty in terms of educational attainment for working-age adults, with the exception of Wyoming, an energy-producing state.

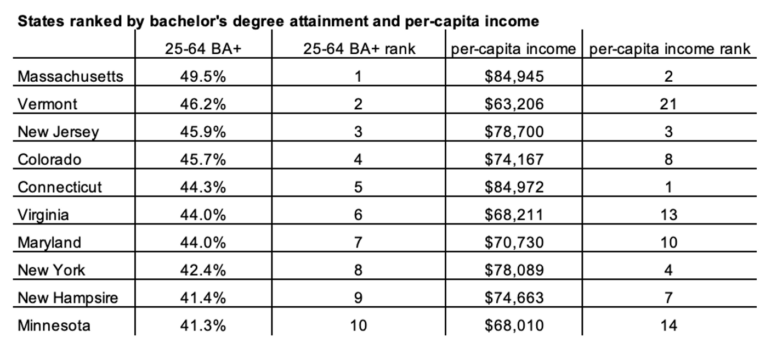

If you rank the top ten states by education attainment (below), the relationship between the two variables is perhaps even more clear. All of the top ten states in education attainment are in the top half of states in per-capita income, and aside from Vermont, are all in the top fifteen. High education attainment appears to serve as a sort of bulwark against being a low-prosperity state.

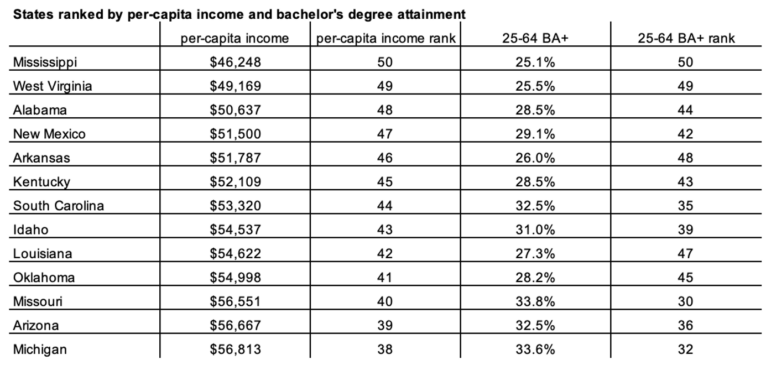

If we look at the states with the lowest per-capita income, it becomes even more clear just how linked educational attainment and prosperity are. Here, we show the bottom 13 states ranked by per-capita income in order to include Michigan, which can now be defined as a low-prosperity state. All of these states are in the bottom twenty states in educational attainment, with a BA attainment rate for working age adults below 34%.

These tables, as stark as they are, actually underplay the association between education attainment and per-capita income, because by simply looking at rankings we don’t consider the magnitude of the difference between high per-capita income/educational attainment states and the low per-capita income/educational attainment states. The per-capita income in Massachusetts (~$85,000) is nearly double that of Mississippi (~$46,000), as is the rate of working-age adults with a bachelor’s degree (49.5% in Massachusetts versus 25.1% in Mississippi) – nearly a difference of kind than of degree.

Educational attainment and per-capita income at the metro level

This same relationship between educational attainment and per-capita income is also present at the metro level; indeed, because talent concentrates in metropolitan areas, it’s the differences in educational attainment and per-capita income at the metro level that drive the differences we see across states.

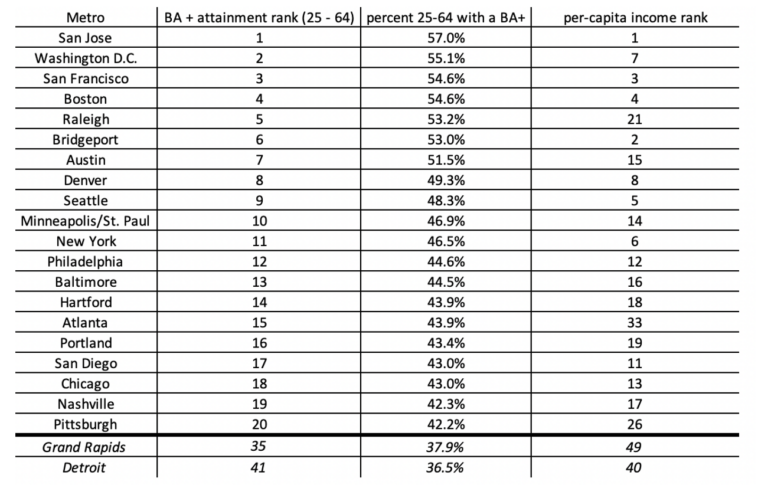

The chart below shows the twenty metropolitan areas with the highest shares working-age adults (25-64) with a BA or more, out of all metros with at least 500,000 working-age adults. We also include the Grand Rapids and Detroit metro areas, with their respective rankings. The final column shows where these metro areas rank in per-capita income. Aside from Raleigh, Atlanta, and Pittsburgh, all of the top twenty metros in BA attainment are also in the top twenty in per-capita income.

And if we look back to the highest prosperity states, aside from Wyoming, all of the high-earning states are home to a high-attainment metro area (the Boston metropolitan statistical area includes parts of New Hampshire). This is because metro economies drive state economies, with talent concentrating in metro regions. Sixty-eight percent of all working age adults with a BA or more in the U.S. live in one of these big metro areas, with 46% of them living in the twenty most populous metros. When we’re talking about talent attraction and retention at the state level, we’re really talking about talent attraction and retention in our metros, and our large metros in particular.

Why does the connection exist? And why should we care?

The reason educational attainment and per-capita income are so inextricably linked is simple: more highly educated people means more people are employed in the high-wage knowledge economy, and more high-wage knowledge-economy jobs migrate to or are created because of existing talent concentrations. These are jobs in managerial, business, finance, professional service, information, education, and health care professions. The average median income for occupations that require at least a bachelor’s degree is nearly $90,000; for those occupations that don’t require a bachelor’s degree, it’s roughly $48,000.

But, one could argue, should high per-capita income be our goal, if it’s simply capturing the relative number of high earners in a state? How does the presence of a large number of highly-educated, high wage workers enhance the well-being of those without a college degree?

First, more high-wage workers means more spending in local economies – in professional services, construction projects, food-service, retail, etc. – leading to more jobs and higher wages, for all workers. Retail workers in Massachusetts earn, on average, two dollars more per hour than retail workers in Michigan; electricians earn nearly $10 more.

Second, more high-wage workers also means more tax revenue – the per-capita income state rankings line up quite well with state rankings of tax revenue per capita. More revenue means increased ability to make a range of investments in public goods and social supports – education, health care, housing, public assistance, public space, and infrastructure – to enhance quality of life for all residents.

And finally, more highly educated, high-wage workers means more knowledge-economy industries flocking to your state, which means more opportunity for residents of that state, and their children, to access high-wage knowledge economy jobs.

Because our metro and state economies are so dependent upon the educational attainment of our metro regions and state, we have been arguing for years that our economic development focus needs to be primarily centered on developing, retaining, and attracting talent. In future posts, I’ll explore how we do that, and how our state and regional policy agendas would look profoundly different if developing, retaining, and attracting talent was our primary economic development focus.