It now seems certain that the coronavirus pandemic will be with us well into the 2020-2021 school year, or beyond. While some school districts are starting to release plans, many of these plans still feature large “wait and see” or “depending on directives from the health department” components. But it seems increasingly likely that distance learning will be a part of most children’s education in the coming school year, whether on a regular, planned weekly basis, or at occasional interruptions due to local outbreaks or possible exposures, or due to high risk factors and families choosing to stay home.

This spring, I, like many parents, had my first experience with trying to be the leader of my kids’ education. How’d it go, you ask? Well, while there were some highlights—I enjoyed watercolor painting alongside my girls and looking at leaves through my daughter’s microscope—overall, it was tough. My husband and I were both still trying to work, and our school’s response (and my daughters’ ages, 5 and 8) meant that parents had to be highly involved in the day. Obviously, that doesn’t work for every family, and it could only work in the short term for mine.

So, before writing a few upcoming posts on what we, as a state, should be doing to plan for the next school year, I’m offering a few reflections on what I learned as a reluctant but engaged homeschool parent.

1 First and foremost, confirmed that I did not miss a calling to become a teacher!

2 The muscles required for lifelong learning—the “learn to learn” skills—are much harder to teach than how to count by fives or how to read words that end in -ad. My suspicion is that they are also the most difficult to foster remotely without great intentionality. Patience, grit, critical thinking, being organized, focusing for longer periods of time… without the constant engagement and gentle redirection of adults, kids on their own don’t just magically possess these skills once they reach a certain age (there is a development readiness component for them, but they’re not then automatic). I’m an enthusiast of project-based learning, and tried to test out my enthusiasm with a couple of longer-term projects with my kids. It was really hard. The biggest challenge was that, at their ages, they don’t naturally stay interested in one topic or idea over more than a few days. I had to keep finding ways to make it interesting. Sustained interest is its own muscle that needs building!

3 Teaching social-emotional skills like communication and collaboration without fellow communicants and collaborators is a real challenge. I basically see the entire point of preschool to learn how to get along with others. And unlike math or reading, these skills cannot be taught in the traditional sense. They are fostered when we provide experiences or environments where our children can learn them. The gentle guidance of preschool teachers helps model and mold positive relationships and skills like conflict resolution among the children in their class. In other words, I worry that in our social isolation, my five-year-old may be gaining in things kids can get from lots of adult attention, like a larger vocab. But without the diversity of her classroom, she may be losing the most in terms of learning how to be with other people. I mean, right now she shares DNA with everyone she sees. It’s not healthy!

To my mind, the closest substitution has been to rely on children’s literature. Children use narratives to make sense of everything (actually, so do adults). When we can’t see other people, empathizing with the characters in stories feels like the next best thing.

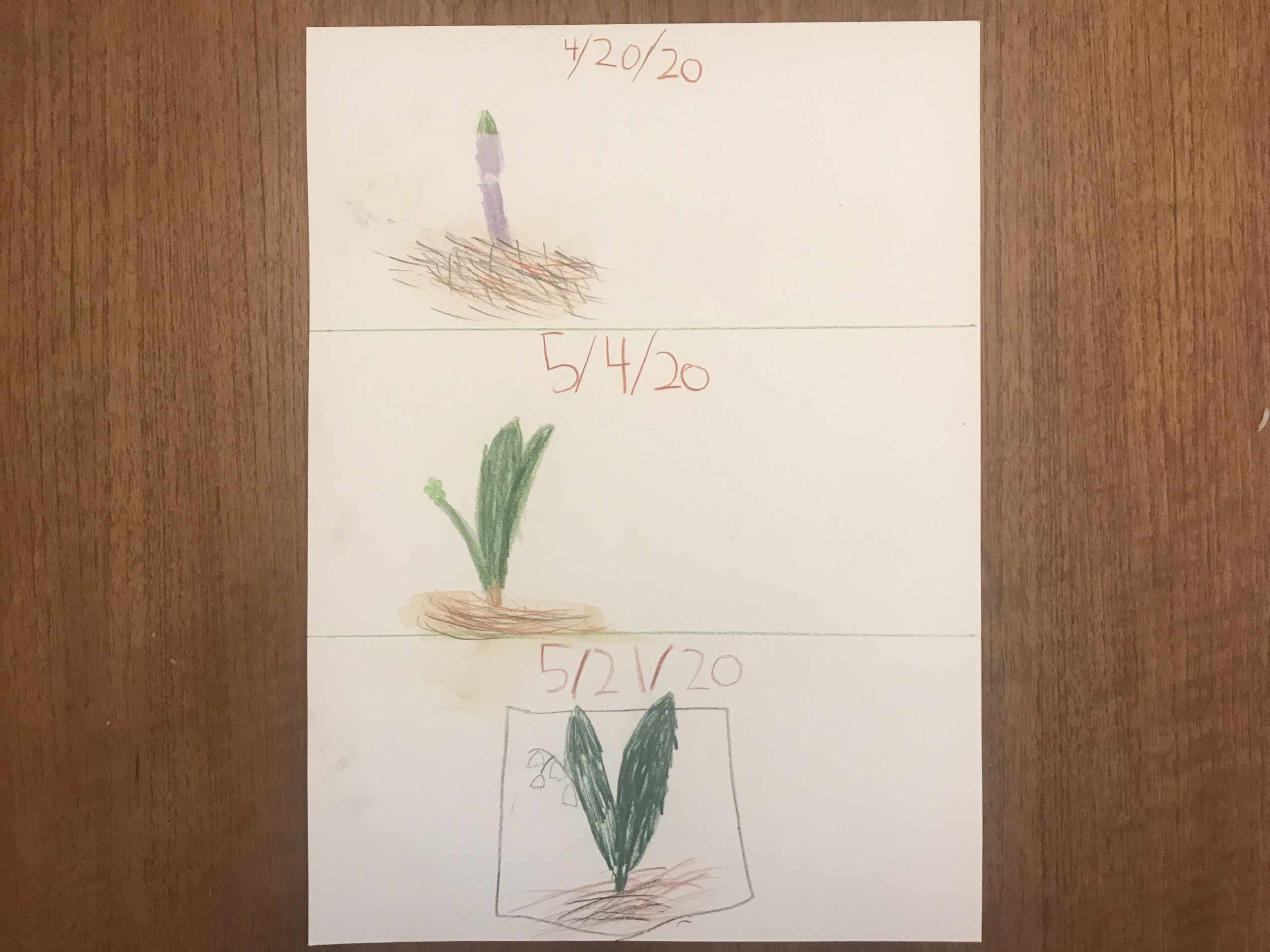

4 On the other hand, there is an opportunity to really lean into the teaching of creativity in this remote environment, which invites parents to tap into their creativity as well. We had paint, clay, crayons, and all sorts of crafting supplies available to the kids constantly. In our family, we reference a book called Beautiful Oops on a regular basis, a young children’s book about how mistakes can become something wonderful (purchased in response to one child’s perfectionism). I saw my kids grow in the flexibility and nimbleness of thinking with the more they made and re-made. When clay projects broke or didn’t come out how they expected, we talked about why. We repurposed lots of household items to make art. Even simple painting can heighten their ability to observe the world with depth and focus, other skills that I value more highly than whether the horse they made really looks like a horse (I also found that it dovetails nicely with science when it involves practicing observation of the natural world). Higher level creativity, according to the book Becoming Brilliant, a frequent reference point for us at MFI, also requires a knowledge of what comes before you. But the simple practice of creativity, a practice that includes experimentation and messing around to see what happens–a focus on process over product–comes naturally to kids. It’s something I’d like to help them preserve, and it’s something that a lot of schooling—where there is one “right” answer—undermines.

5 Supplementing with online apps isn’t worthless, but it isn’t worth much without a lot of oversight (basically defeating the purpose of buying some free time for adults who are also trying to not lose their jobs or sanity while socially isolating with their kids). In my view, this is primarily because these apps are designed as a series of modules that lack the ability to integrate their instruction with knowledge kids already have. An illustration:

“Mom, today I learned about graders on the app,” my eight-year-old told me one day.

“Graders? What do you mean?”

“Like, it’s a shape that’s sort-of like a triangle and it goes between two numbers.”

I eventually realized my daughter meant she had been learning about “greater than” and “less than” and the mathematical sign for these comparisons. But somehow, she had gone through this lesson without realizing that the app was just trying to provide a mathematical nomenclature for a concept she already understands. Yet somehow she managed to learn about “graders” on the app, without understanding how it was connected to the real world, where knowing a difference between quantities is easy (especially if the quantities are of something good, like M&Ms, and the difference is between her and her sister). Brain science tells us that people learn the most successfully when they are able to make connections between something new that they learn and things they already know. So while it should have been easy to integrate the greater than/less than concept to other concepts my daughter understands, the app hadn’t managed to do that. It was just a totally new idea to her, floating around in her brain, untethered to anything that would help it stick.

6 I really do not know how to give feedback to young children in a way that they can take constructively. It may just be that that is an intrinsic part of mother-daughter dynamics, but it feels like a really big missing piece here. It’s less important for my five-year-old. “Wow, you worked so hard on that,” cuts it in a lot of scenarios for her, and I know that whether she draws her 5s backward right now is just not essential to correct. But for my now second-grader, providing gentle correction to her writing is appropriate. She hates it. And I’m pretty sure she doesn’t hate it when it comes from her teacher. Somehow the stakes are lower, and her teacher is skilled in how to do this. And feedback is absolutely critical to learning.

7 Online learning is naturally a barrier in student engagement. For students to learn deeply, they have to be deeply engaged in the learning. My observation was that while going virtual was at the outset pretty exciting to my kids, who otherwise are permitted only limited screen usage, that interest waned. I think it became almost painful to them to experience such a poor facsimile of real human togetherness—a phenomenon every “zoomed out” professional can probably understand. Good remote learning is going to have to plan around that type of disinterest.

8 If you’re worried about screentime, there are so many good kid podcasts and audio books out there that can buy you some time. Honestly, sanity-saving!

In my next post, I’ll try to broaden from my personal experience out to reflect on the larger community experience of remote learning, and look a little at how districts are responding.