Last week I wrote about “Outsmarting the Robots: Redesigning education from the classroom to the halls of Lansing,” an event we co-hosted in October with a number of great partners in Grand Rapids. (Click here for that part 1). Today I want to share a little more about the day.

I already told you about the debates that ensued when participants took a few sample standardized test questions. Were these questions relevant to the skills that matter? Are they good measures of how well a school is preparing them for the future?

But earlier that morning, we had a chance to hear directly from four middle school students who attend the Grand Rapids Public Museum School, a public school located in the Grand Rapids Public Museum, and a 2016 winner of the XQ “Super School” award of $10 million for innovation in education. The school prioritizes design thinking, inquiry-based education and fosters critical skills through authentic projects—not worksheets.

Hearing directly from four students at the school, who weren’t prepped in any way except to “be honest,” was captivating. A few things they said stuck out to me. First, their descriptions of great learning experiences were all descriptions of projects, and on topics that had clearly captured their interest. Their identities had started to become connected to the projects that had fascinated them.

On the subject of standardized tests, one said that she feels they do a poor job of capturing how much she knows and understands about a topic. She said that the presentations she has to do at her school are a much better chance for anyone to really gauge what she has learned. “Because you have to be really prepared for questions you might get, so you really have to know what you’re talking about.” This matches the decisions of many progressive schools to invest in portfolios and public presentations to showcase student work in a meaningful way, rather than relying on testing. Another student shared that he gets really anxious about tests. “My grade in math is really good, but it’s stressful because if I don’t do well on this one test, I won’t be in honors math next year.”

And responding to a vital question about how they feel about the fact that this school is based on a lottery and doesn’t serve everyone who wants to go there, one student said frankly, “Every school should be like this.” The other young people echoed this: each school should have a way of being highly and deeply engaging. The students recognized that it “wasn’t fair” that they got to attend the Museum School while others didn’t.

It’s exciting to have this type of innovation in our backyard. Now we need to figure out how to make sure every child can access it. The equity implications were obvious to the kids, and they thought the grown-ups should fix it.

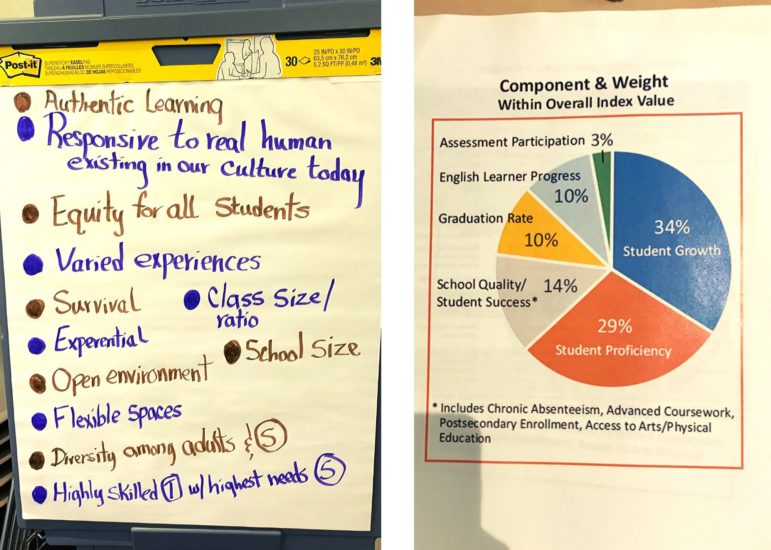

In the afternoon, conference participants participated in a design simulation where, in groups, they used legos to build their ideal school—designed to serve the children in their own lives (we observe that people are most ambitious when thinking about their own children or other children they know and love). They first listed the type of characteristics and features they wanted to prioritize. Then they build a representation with legos. But during the building process, facilitators added conditions: some legos had to be reassigned due to a new literacy program, for example. When the building was done, participants received a pie chart showing the new Michigan School Index System—a new method for evaluating school performance. In all, standardized tests account for almost 70 percent of a school’s rating. Participants were asked: will the school you designed perform well on this index? One intrepid group said that they had faith that treating the children more holistically and developing broader skills—as their group hoped to do in their school—would still payoff in the rating system. Others expressed feeling that there had been a “bait and switch.” I heard educators explain the ways this indexing system influenced teachers—incenting them to give undue attention to standardized test prep. “It just doesn’t match,” was the most common refrain. This system doesn’t match the priorities we would set for our own kids.

If what you measure, matters, then it really matters that we are measuring the wrong things.

Look, this was an experience designed to generate this kind of conversation and dissatisfaction. But it’s not hypothetical. Our system is designed to measure test-taking almost exclusively. It is not designed to measure the development of critical skills, like collaboration and critical thinking (which our keynote speaker, Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, co-author of Becoming Brilliant, reminded us are both malleable and measurable). Therefore, we are getting schools that are trying to develop test-takers and not trying to develop collaborators and critical thinkers (despite the motivations of most teachers who got into the business to develop young minds!).

The system is powerful, and it’s pushing and pulling in the wrong direction.

This gets at the heart of why we wanted to co-host this event. Our schools need to be redesigned to build the skills of the future, and there is a fundamental mismatch between the policy system and the features and outcomes that should be our priorities. We hope “Outsmarting the Robots” helped participants imagine what’s possible for schooling, feel discontent–or anger–at the system we’ve got now, and get motivated to be a part of changing it.

[For another perspective on the day, I’m also glad to share this write-up from Erin Albanese, a journalist with the School News Network who observed the entire conference.]