Many believe that we have a student loan “crisis” on our hands. And indeed, the total level of outstanding student loan debt – ![]() $1.4 trillion at present – is striking. However, cumulative numbers like this, generally presented as evidence of the “crisis,” actually tell us very little about the actual impact of loans and debt on individual students.

$1.4 trillion at present – is striking. However, cumulative numbers like this, generally presented as evidence of the “crisis,” actually tell us very little about the actual impact of loans and debt on individual students.

In October of last year, the federal government released new data on student debt and repayment that offered the most comprehensive picture yet of exactly who is having trouble paying back their student loans, and at which type of institutions, allowing us to take a more nuanced look at the student loan landscape. The picture is both better and worse than most people think.

The for-profit sector is responsible for much of the damage

What primarily jumps out from this new set of data is the outsized role the for-profit sector plays in the student loan “crisis.” While 17 percent of all students that began college in 2004 had defaulted on their loans within 12 years of college entry, a full 47% of students that started at for-profit colleges had defaulted within that same time span. Based on existing default rates and patterns from past cohorts, Judith Scott-Clayton of the Brookings Institution projects that 70% of the 2004 for-profit cohort will default by 2024.

In other words, if we do have a student loan crisis on our hands, it’s for-profit colleges that are driving it.

Graduation and four-year degrees really matter

Susan Dynarski, an economics professor at U of M, has written for years that what we see as a student debt crisis is actually more of a college completion crisis. It turns out that those that get into trouble paying back student loans generally don’t have a lot of debt – because they didn’t spend enough time in college to complete their degrees. So they leave college with a relatively small amount of debt, but with no credential to help them earn a wage premium in the labor market. College graduates tend to carry more debt, but are earning enough that they have little trouble paying it off.

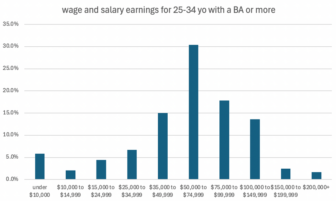

This new data again emphasizes the importance of graduation, and the importance of earning a valuable credential. Of the 2004 cohort, just 5.6 percent of students who attained a bachelor’s degree defaulted on their loans within 12 years. This is three times lower than the rate for all students, and reflects the fact that the bachelor’s degree wage premium continues to rise, enabling BA holders to easily pay back their loans.

These same positive outcomes do not hold for those that earn an associate’s degree or occupational certificate. 14 percent of the 2004 cohort that earned an associate’s degree defaulted within 12 years, and 28 percent of those that attained a certificate defaulted, despite average loan burdens far lower than for those who earned a bachelor’s degree. This is driven both by greater participation by for-profit institutions in the sub-baccalaureate space and uneven returns for sub-baccalaureate credentials.

Regardless, the higher rates of default among sub-baccalaureate completers is an important finding. The risk of student loan defaults is often cited as a reason students should avoid attending a more expensive four-year institution, and opt instead for cheaper two-year schools. This data suggests that passing on a four-year school may in fact be the far riskier option.

Black BA holders

The most disappointing finding from the data was that the low default rates for those that earn a BA do not hold for black students. While just 4 percent of white BA holders defaulted within 12 years, 21 percent of black BA holders did, an unacceptably high number.

What’s driving the high number of defaults? Evidence suggests that black recent-graduates face discrimination in the labor market, with an unemployment rate double that of white recent-graduates. Black students are also more likely to attend lower-selectivity colleges, whose alumni experience lower earnings and higher default rates.

But a major factor also appears to be patterns in graduate school borrowing among black college graduates. Perhaps because of relatively poor labor-market outcomes, black college graduates are now more likely than white college graduates to attend graduate school, a relatively recent phenomenon. But the increase in graduate school attendance among black college graduates has been almost entirely driven by attendance at for-profit graduate schools, with almost 30 percent of all black graduate school students attending a for-profit institution.

As is the pattern in the rest of the for-profit sector, these students borrow significant sums to attend these institutions, yet see little return on their investment in the labor market.

Counseling, counseling, counseling, and counseling

The reason I keep putting scare quotes around the word “crisis” in this post is because taking out student loans shouldn’t be all that scary. Yes, college needs to be far cheaper, and we need to commit dramatically more public funds to make it cheaper. But under our current system, in which a a four-year college is really expensive, yet offers the best pathway to good-paying work, loans are a necessary tool to give all students access to higher education. And scaring students away from taking on debt makes it less likely that they’ll attend college, less likely that they’ll persist, and less likely that they’ll graduate. This is a problem because even if a bachelor’s degree doesn’t guarantee economic success, it certainly offers a far better chance of being employed in a good-paying job than other potential paths.

What’s needed instead is more and better counseling at all stages of the college process. This means counseling high school students into colleges with high graduation rates and good financial aid; counseling students to take on appropriate levels of federal student loans; counseling students to persist through to graduation; and then counseling them to enroll in income-based repayment systems to prevent loan defaults.

The right kind of loans, for the right kind of education, can be the best investment of a student’s life. It’s our job to make sure that it is.