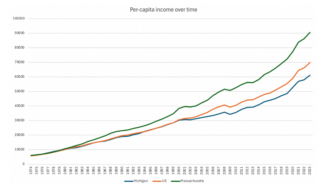

Our latest report, Sharing prosperity with those not participating in the high-wage knowledge-based economy, is ![]() based on two major understandings. The first is that even in a growing economy, a large portion of the population can still be struggling. Indeed, this has been the story of our economy since the 1980s, as the economy has continued to grow but median incomes have been stagnant or declining and job growth has slowed, largely a result of increased automation.

based on two major understandings. The first is that even in a growing economy, a large portion of the population can still be struggling. Indeed, this has been the story of our economy since the 1980s, as the economy has continued to grow but median incomes have been stagnant or declining and job growth has slowed, largely a result of increased automation.

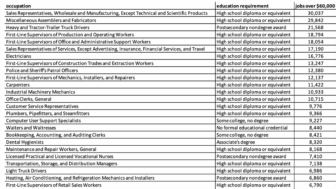

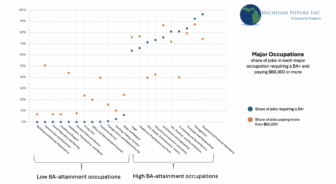

The second understanding is that this situation won’t be solved by market forces alone. The market is simply not creating enough jobs that pay a family supporting wage, or efficiently matching workers with opportunities. The clearest illustration of this fact comes from the recently updated ALICE report put out by the Michigan Association of United Ways, which shows that 40% of Michigan households are unable to afford basic necessities. Over 60% of these households are led by a working adult, but the majority of available jobs – both today and for the foreseeable future – are low-wage.

It’s within this context that we make recommendations in our report for how we can get more individuals into family-supporting work.

There are two prongs to our approach. One is to increase the number of good-paying jobs available to all Michiganders, through public policy levers. This will be the subject of my next post.

But this first post is dedicated to how we get individuals into the jobs that are available, by helping them overcome the range of barriers that often stand between them and stable employment.

Why don’t people work?

The barriers individuals face in finding and keeping a job can range from the minor to the seemingly insurmountable. Potential barriers include everything from being unable to find job openings; lack of adequate housing, transportation and childcare; lack of general or job-specific readiness skills; physical or mental health issues; a history of addiction or incarceration, or anything in between. And evidence suggests that few unemployed workers face just one single barrier, but rather are dealing with a range of interrelated issues.

It’s also important to understand that the popular narrative of individuals not working and simply living off of safety-net benefits is, essentially, wrong. In the first place, relatively few poor families in America receive any cash benefits anymore – just 16% of all Michigan families in poverty. But even when a far larger portion of the low-income population did receive benefits, the vast majority did in fact use it as temporary assistance while they found employment, while those that ran up against time-limits were those that faced the largest obstacles to employment.

In fact, a generous safety net may even encourage a higher work rate. Minnesota’s safety net is far more generous than Michigan’s. Yet 67% of Minnesotans over 16 work, versus just 58% in Michigan. If Michigan had the same work-rate as Minnesota, 800,000 more Michiganders would be employed today. If a stronger safety net encourages some sense of stability – the ability to afford rent, transportation, or child care – that enables individuals to find and keep a job, a strong safety net could indeed encourage increased employment.

How to help people find work

Our social safety net is built around work. If you lose your job through no fault of your own, you can claim unemployment insurance while you get back on your feet. If you’re poor, you’re eligible for cash assistance through the TANF program, with the understanding that you’ll be engaged in activities designed to get you on the path to work.

The premise of these programs is that while no one has an entitlement to cash assistance, everyone is entitled to the opportunity to attain well-paying work.

The welfare reforms of the mid 90s were built on this central idea: cash supports would now be temporary, but the government would put more resources into ensuring people had the supports needed to put them on a path towards a family supporting wage.

Michigan’s safety net has failed on both of these fronts. Through policy changes and underinvestment in the state’s TANF system and unemployment insurance system, a large chunk of out of work Michiganders receive little to no cash assistance, nor do they receive the supports needed to obtain family-supporting work.

Our solution, as detailed in our report, is built around two pillars. The first pillar is to make it easy for those out of work to receive some form cash assistance. Cutting cash benefits both removes some semblance of stability for poor families, and removes the individual from the system of supports that can help put them on a path to family-supporting work. We should want Michiganders to be able to access benefits, both to provide desperately needed stability, but also to connect parents to valuable work-supports.

This means removing arbitrary lifetime limits on the receipt of cash assistance, increasing the generosity of cash benefits in both our welfare and unemployment insurance system, and using TANF dollars for core TANF purposes (cash assistance, work-related supports, and childcare assistance), rather than using the funds to plug holes elsewhere in the state budget.

Paired with a more generous safety net, the second pillar of our plan is to dramatically increase the supports individuals receive to get on the path towards family-supporting work. Our proposed approach is based on a 2014 House Budget Committee report by Paul Ryan titled Expanding Opportunity in America. In the report Ryan describes a system in which all supports would revolve around a central caseworker who would refer clients to a range of service providers, help them navigate a thicket of services and benefits, and recommend potential educational and job-placement pathways.

This approach offers the flexibility to offer comprehensive and customizable supports to a range of individuals – from those facing multiple barriers to employment to those that are just temporarily out of a job – and has the potential to support individuals not just into a first job, but through multiple steps on the path to family supporting work. In a hypothetical case Ryan presents, a case manager guides a client from an entry-level retail job all the way through to college graduation and a full-time teaching position. Safety net benefits continue until the recipient is in stable good-paying employment.

This is a far different approach from traditional workforce development services, which have traditionally focused on job-seeking skills (e.g. interview and resume prep), and measured success by first-jobs and benefit reductions.

Such a plan would not be easy, nor inexpensive, to implement. It would require highly-qualified, well-paid caseworkers; shifting our definition of success from short-term employment to long-term financial well-being; and offering comprehensive services not only to those in poverty, but to workers across the economic spectrum in need of support. But without those supports, the story that’s played out over the past two decades won’t change.