Many states have cut benefits to the poor and unemployed in the belief that these payments dissuade people from looking for paid work.

Minnesota takes a different view. It has created one of the strongest safety nets in the country, spending generously on benefits to help those who have lost jobs or been stricken by poverty get back on their feet.

That protective net has not trapped Minnesotans and turned them into a bunch of government-dependent slackers. Far from it.

Minnesota’s employment-to-population ratio of 67.2 percent in April was the fourth highest in the country, according to the latest data of the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project.

In Michigan, which has trimmed welfare and unemployment benefits, 56 percent of the adult population was working in April. Michigan ranked 41st in that measure.

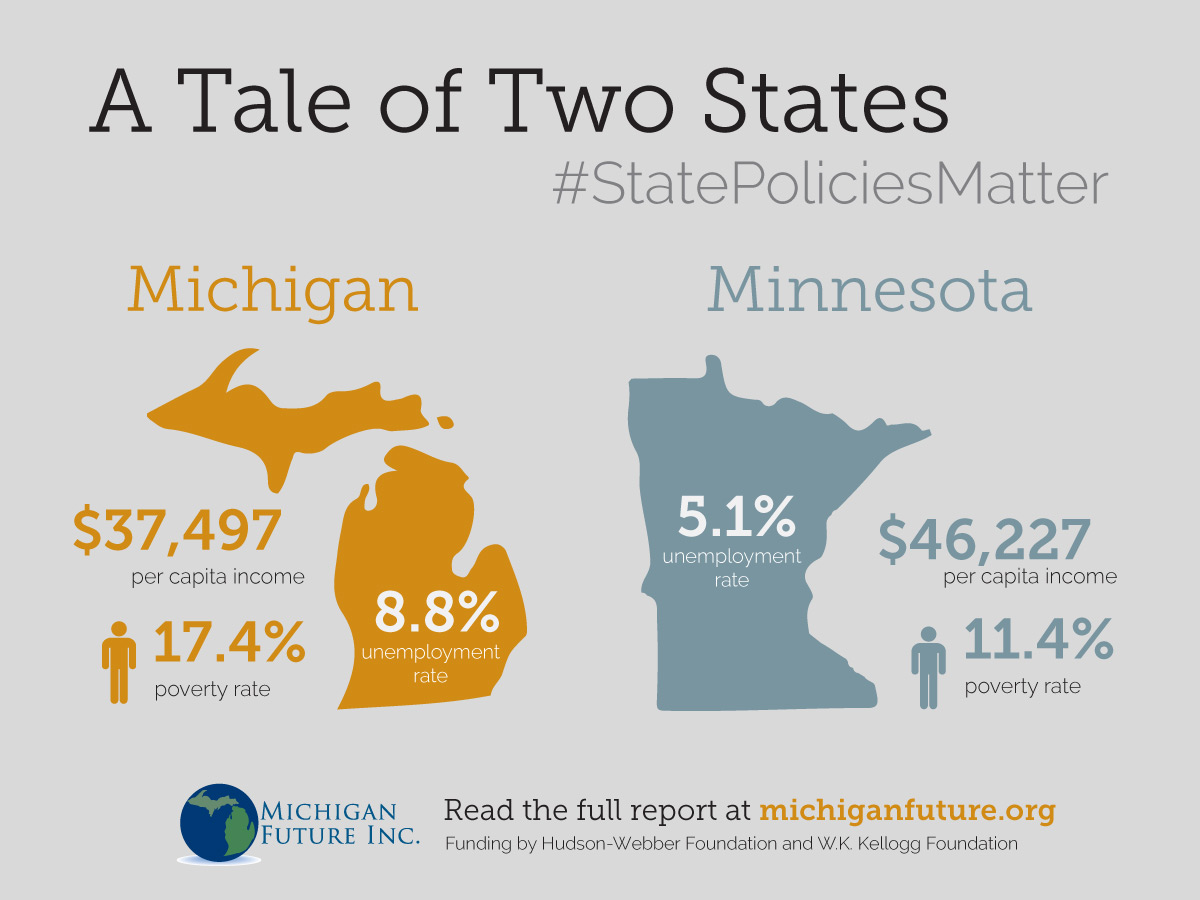

Minnesota’s jobless rate of 4.5 percent in June was the 10th lowest in the country, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Michigan ranked 47th with an unemployment rate of 7.5 percent.

In 2013, Minnesota spent $6.4 billion, or $1,134 per person, in state resources on health and human services. Michigan spent $6.1 billion, or $617 per capita on these services.

Minnesota spent $8,680 per person on public welfare for those below 200 percent of the federal poverty line, more than any other state except Alaska, according to a March 2013 study by the Center of the American Experiment, a conservative think tank in Minneapolis. Michigan spent just under $4,000 per person.

Lifetime cash assistance benefits are limited to 60 months in Minnesota, in line with federal law. Michigan trimmed its lifetime limit to 48 months in 2011.

But just 11.4 percent of Minnesotans were living in poverty in 2012, according to the Census Bureau. In Michigan, 17.4 percent of residents were living below their respective poverty levels. The U.S. poverty rate was 15.9 percent in 2012.

Michigan and Minnesota have recently enacted higher minimum wages, but Michigan lawmakers did so mainly to head off a ballot proposal that would have boosted the state minimum wage to $10.10 an hour from $7.40 an hour.

Minnesota’s minimum wage will rise to $8.00 an hour on August 1. It will jump to $9.00 an hour on August 1, 2015 and $9.50 an hour on August1 1, 2016. It will be indexed to inflation starting in January 1, 2018.

The state has a lower minimum wage rate for small businesses with annual sales revenues of less than $625,000. That rate will for those employers will be $7.75 an hour on August 1, 2016.

Minnesota does not allow employers to take a tip credit. Employees must be paid at least the applicable minimum wage plus any tips received.

Michigan’s minimum wage is scheduled to rise to $8.15 an hour on September 1. It will rise in steps to $9.25 an hour on January 1, 2018 and will be indexed to inflation on January 1, 2019. The minimum wage for workers receiving tips will be 38 percent of the new minimum wage.

Minnesota also provides more generous jobless benefits than those offered in Michigan.

Jobless workers in Minnesota are entitled to a maximum state benefit of $610 a week for 26 weeks, nearly 70 percent above Michigan’s maximum weekly payment of $362.

In 2011, Michigan cut the time jobless workers can collect state benefits from 26 to 20 weeks in 2011, the fewest of any state at the time.

Since then, seven other states have cut the number of weeks jobless workers can collect unemployment benefits.

A new study by the Economic Policy Institute found that there has been no “visible improvement state labor market outcomes (specifically, the employment-to-population ratio of workers age 25 to 54)” in states that cut benefits.

Read #StatePoliciesMatter, Michigan Future’s latest report, here.