On October 21, Michigan Future co-hosted a convening in downtown Grand Rapids for 60 community leaders called Outsmarting the Robots: Redesigning education from the classroom to the halls of Lansing. The goals of this half-day event were:

- To help catalyze a transformation in youth-serving organizations, including schools, in and around west Michigan, such that those organizations define their work as fostering broad, 6C skills in all youth (see a previous post for a definition of “6Cs skills”).

- To catalyze advocacy for policy change that will enable schools to become 6C-fostering environments.

- To help stakeholders understand that we need to rethink school design; simply executing the current design for schooling more effectively will not prepare our kids with the skills they need.

We decided that we would approach these goals a little differently from a standard conference format. Instead of lecturing participants, as in a traditional model that educators might describe as “sit and get” (so called for what the students are doing)–we would try to model the type of learning experiences that we think are so critical to education for today and the future. These learning experiences involve greater autonomy for participants, engaging their knowledge, past experiences, critical thinking capacity, and ability to draw connections, all multiplied by the power of collaborating with a group. They let people come to their own conclusions which are then more deeply integrated into their existing “wiring;” in other words, more likely to be not just heard, but really learned.

Thankfully, we had wonderful partners who know how to do this not just theoretically, but practically. Godfrey-Lee Public Schools and the Kent ISD are both moving their students toward critical skill development. The Kendall College of Art and Design provided valuable design thinking perspective that helped us shape the day to maximize adult learning. The Institute for Excellence in Education likewise understood how to create learning experiences so that participants are maximally engaged and challenged. And our hosts at the Grand Rapids Public Museum were gracious in providing dynamic space, and have staff who are leaders in inquiry-based education, using the artifacts the museum has in its vault.

After several months of highly collaborative planning, this consortium attempted to lead our participants through a set of experiences that would allow them to answer, for themselves, a series of questions about what education should look like in both the present and the future.

- What skills are critical to success, in work and in life?

- What do we know about the skills that will matter in the future?

- What can a highly engaging learning experience look like?

- How do youth describe great learning experiences?

- What do we know about how people learn critical skills, and the settings where those skills are fostered?

- Are standardized tests relevant to learning critical skills?

- How would you design the ideal school, amid current system constraints?

- Now what? What did you learn today, and what can you do?

- What in your thinking has changed today?

- What are you motivated to do?

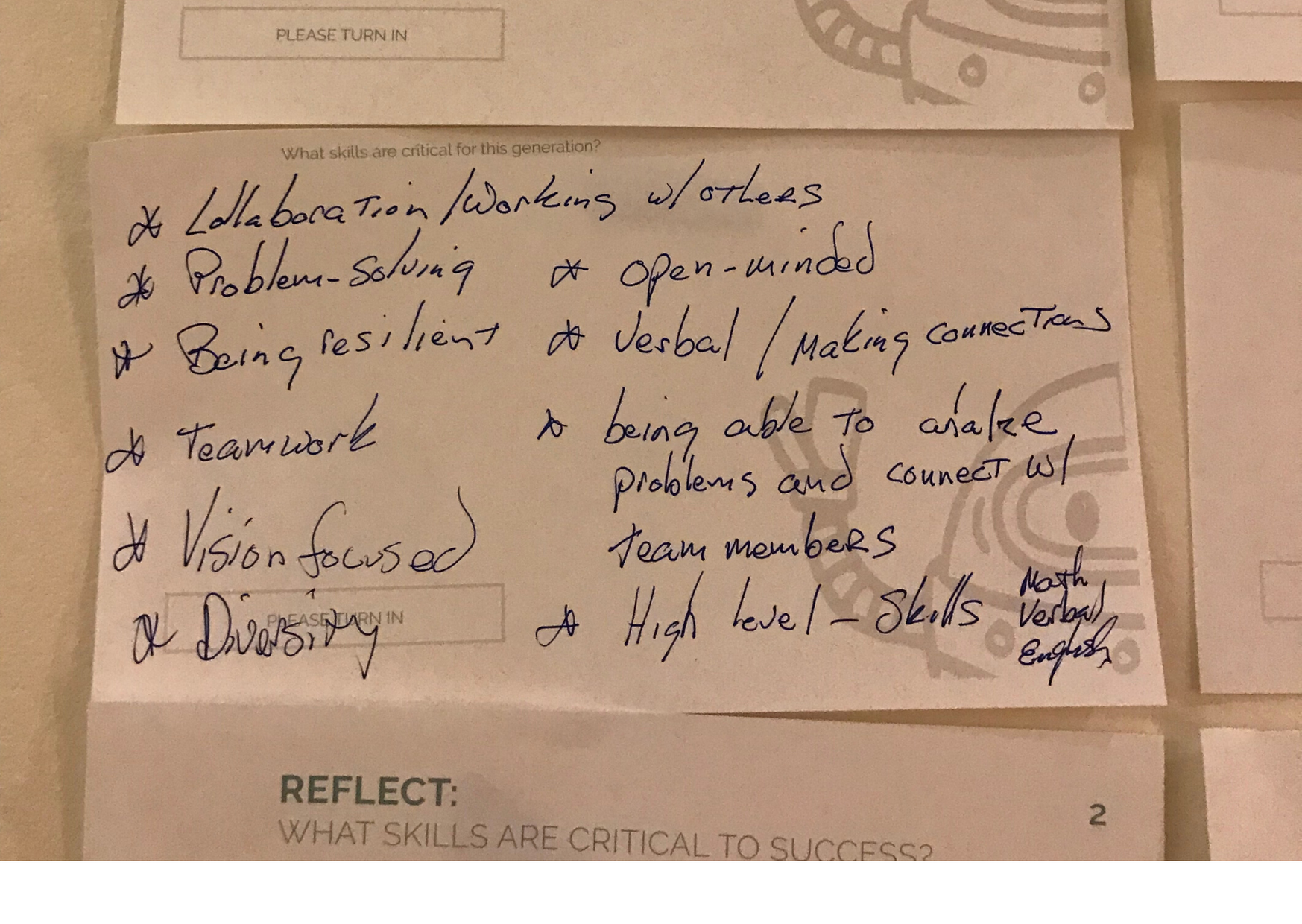

The photo I shared with this post is one fairly representative response card that we collected at the beginning of the day, when we asked participants: what made you successful? You’ll notice that this respondent doesn’t mention great test-taking ability, capacity to regurgitate factoids, or the ability to work alone on projects. And yet, to a great extent, and to the chagrin of wonderful educators everywhere, our political system is turning the screws on schools so that kids have scant opportunity to develop the more sophisticated capacities demanded of the current workforce.

We intend to release a report on the conference later this month. So for now, I will just share some notes on one activity. After spending the morning talking and thinking about engaging learning environments and how they foster critical skills, our participants took five sample questions from elementary and middle school M-STEPs. We provided this activity to prompt people to discuss what role standardized test play in an education system that grows critical skills in students.

You might assume that 60 successful professionals–leaders in business, philanthropy, education, and other civic organizations–would all score perfectly on a test that our state policy values tremendously (and that is designed for 8-13 year-olds!). Yet, that was far from the case. People had a range of reactions. For some, frustration at the “trickiness” of the questions. People noted that they seemed designed to trip up the test-taker. We observed participants debating the “correct” answer, defending the logical train of thought that took them to the “wrong answer” (an opportunity that students should have!). Finally, a number of participants noted the irrelevance of the questions to the skills that we’d discussed earlier in the day–skills like creativity and communication. Whether they could solve these riddles just didn’t stand up as a valuable measure.

Next week, in a second post on the day, I’ll go into greater depth on two of the other activities we conducted, including an exercise in school design, and what we believe people took away.