Some in Lansing would have you believe that our economy is as healthy as ever, with the state’s unemployment rate as ![]() low as it’s been since the early 2000s.

low as it’s been since the early 2000s.

The problem is that the unemployment rate isn’t a great measure of how many people are working (not to mention how much they’re working or how much they’re earning). This is because the rate fails to take into account all of the people who are “sitting on the sidelines,” who don’t have a job and also aren’t looking for one – people who’ve left the labor force.

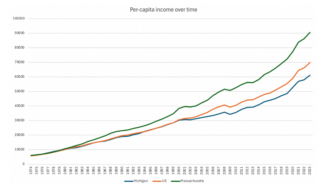

When we take these people into account, the picture – both nationally and here in Michigan – is a lot less pretty. In the booming economy of the late 90s – the last time the economy was thought to be at full employment – roughly 64% of those in the U.S. over the age of 16 were working, versus roughly 60% today, and the employment to population ratio for prime-age workers (25 to 54) was three percentage points higher in the late 90s than it is today. In other words, the unemployment rate doesn’t come close to telling the whole story.

Things look worse in Michigan. One data point we frequently cite is that if the proportion of Michigan adults working today was the same as it is in Minnesota, an additional roughly 800,000 Michiganders would be working. While nearly 67% of Minnesota’s 16 and over population is working today, the same figure is just 58% for Michigan.

This suggests that Michigan’s low unemployment rate represents not a healthy economy, but the thousands of Michiganders who have completely dropped out of the labor force.

How to get people back to work

People drop out of the labor force for a variety of reasons. Some may give up looking for a job because of child care and transportation obstacles; some may qualify only for low-wage, part-time work that doesn’t enable them to afford basic necessities; and some may simply have gotten discouraged, unable to find demand for their set of skills.

While the reasons for dropping out of the labor force are complex, the solution proposed by many policymakers is simple: provide greater “incentives” for individuals to work, which often translates to draconian cuts to safety-net benefits. The theory here is that a strong safety-net provides a disincentive to work, and cuts to the safety-net incentivizes work by giving people no other recourse to get food or healthcare or cash assistance.

It just turns out that the theory is wrong.

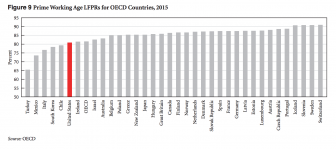

The chart below comes from a paper by Flavia Dantas and L. Randall Wray at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, titled Full Employment: Are We There Yet? The graph charts the labor force participation rates – the percentage of working age people either working or actively looking for a job – in OECD nations. While the U.S. is down around 80%, dozens of countries known for their generous social safety-nets have rates over 85%, with two of the most generous (Iceland and Sweden), up over 90%.

And as for our Minnesota comparison, our Midwestern neighbor hits an employment rate almost 10 percentage points higher than Michigan’s while providing a far more generous set of safety-net supports.

What’s going on here? First, there’s significant empirical evidence that generous benefits don’t, in fact, meaningfully lower work rates. In fact, recent evidence suggests that a more generous safety-net may in fact encourage work participation, not to mention provide a more solid foundation for the next generation. For example, increased child-care subsidies may enable a parent to pursue employment while providing the child with a stimulating and nurturing environment.

All of this suggests two things. The first is that a low unemployment rate doesn’t mean that everyone’s doing well, that everyone who wants a job has a job. This is far from the case here in Michigan. But we also shouldn’t assume that the way to get more people off the sidelines and back into the labor market is to cut more of our already withered social safety net. Instead, it may in fact be necessary to expand the safety-net, and design it in a way that supports individuals back into the workforce.