Last week, I shared observations of my children and their learning during the surprise homeschooling months of the coronavirus pandemic.

Now it’s time to overlay an important lens on that experience: my kids are living in almost the best version of what homeschooling during a pandemic can look like. My husband and I kept our jobs so we weren’t experiencing new financial stress. We don’t work in fields that put our family at high risk of infection, and were mostly able to maintain a careful shelter-in-place. With both of us working at home, we were able to supervise homeschooling and be involved in playtime. We had no coronavirus-related deaths in our family, we aren’t experiencing food insecurity, we both have college degrees. All four of us speak English, have access to health care, and have white skin and the privileges that come with it.

Now, contrast the privileged experience that my kids had this spring with the families described in this article from Erin Einhorn on the lengths that some schools are going to—must go to—in support of children with less class and race privilege than my family. In Detroit’s New Paradigm network of six schools, the administration estimates that a third of students and staff have lost someone close to them during the pandemic. Financial and emotional insecurity, and the demands on parents who are essential workers, create a difficult situation for many families. The school administrators are working as detectives to find the kids who haven’t logged in or communicated with teachers, usually due to other stresses on the family.

So if [New Paradigm Loving Academy Principal Jacqueline] Dungey couldn’t find them — and couldn’t make sure they got the food they needed, or the grief counseling, or the internet connection required to attend their online classes — they wouldn’t be able to learn.

“They’re going to fall further behind,” Dungey said as she prepared to knock on a student’s door last month. “The achievement gap is going to continue to grow, and it’s already wide enough.”

It’s not clear how many schools have the resources to track down students during a crisis. Many states have not required schools to log attendance these last few months, and educators have been overwhelmed with the demands of shifting to remote instruction, changing the way they distribute meals to needy families and figuring out how to support students with disabilities while also suddenly having to instruct their own children, who have been underfoot.

Of course, the digital divide isn’t just a Detroit or urban problem. As Bridge reports, in some rural districts over half of students lack access at home.

In other words, what we’re learning as a community about remote learning during a pandemic is that the longer it goes on, the more we risk instability and educational loss for children who are already the most vulnerable and most likely to be judged to be behind. In fact, in some ways, we’re seeing what we’ve always meant when we call children “vulnerable:” one additional challenge means immense disruption.

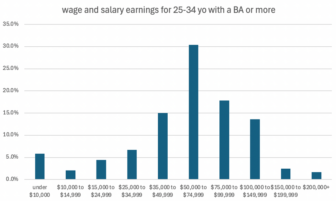

Before coronavirus, we already had an equity gap in education that no one has figured out how to significantly reduce. You might have heard this called an “achievement gap,” but I prefer the more accurate “opportunity gap.” The gap isn’t between the amount of achievement of different kids but the amount and quality of opportunities and investment we (as a state) make in them.

In Michigan, our schools are funded at wildly different levels that correspond to the affluence of the community. The richest kids get the most money; the schools with the poorest kids, nonwhite kids, and immigrant kids get the least. Kids from affluent communities are expected to go to college; kids in poor communities are supposed to be delighted with career training opportunities offered in high school.

And that was before coronavirus. An assistant superintendent from the west side of the state worried to me, “The opportunity gap is going to become a chasm.” While making the quick pivot to online learning this spring, her district had to figure out how to serve the large portion of kids whose parents don’t speak English or own a computer.

While I believe educators in poor districts are as resourceful, skillful, and determined as those in affluent districts, they have a lot more to figure out. For their families, school is a critical hub of support. Yet their districts have fewer resources to apply, and are looking at large budget cuts next year.

We are likely to see a growing distance between the standardized test results of rich and poor districts when the coronavirus is over. The inclination to double-down on teaching testable material in the squeeze is going to be difficult to overcome (for an explanation of how the focus on testing hurts the teaching provided to lower-income students, see my former colleague Pat Cooney’s critique of the 3rd grade reading law).

But that gap will severely under-measure the damage done, the size of the chasm. This is because—even without coronavirus—we don’t currently measure the growth in children of vital skills like critical thinking, collaboration, and creativity, which ultimately make a world of difference in a person’s ability to complete college and compete for good-paying jobs in today’s economy. We don’t have a state plan for building those skills without a pandemic, and we certainly don’t have a plan for building those skills with a pandemic.