The call to action we co-authored with economic and community development leaders from across the state was released just prior to the pandemic slamming Michigan. It calls on our state, regional and community leaders to make rising household income for all a preeminent priority of state and local economic policies and programs.

To make the case for a rising income for all as a state economic priority the call for action cites data that, despite a strong economy and historically low unemployment rate, around four in ten Michigan households were struggling economically.

To us the data make clear that the preeminent reason so many Michigan households struggle to pay for basic necessities is that the economy is producing too many low-wage jobs. This is structural. We are not growing our way out of too many low-wage jobs. Lots of businesses that employ lots of people have business models based on low-wage workers.

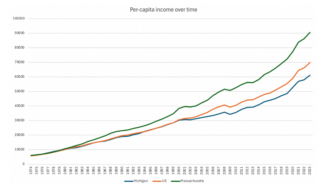

Michigan’s wages and employer paid benefits per capita are 14 percent below the national average. As recently as 2000, Michigan’s wages and employer paid benefits per capita were one percent above the national average.

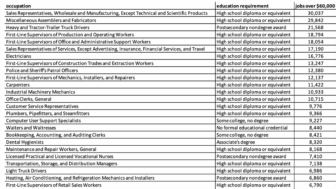

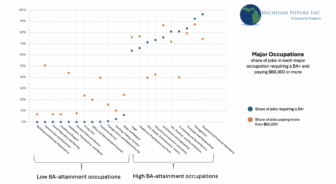

Sixty percent of Michigan jobs pay less than $20 an hour. A full 40 percent pay less than $15 an hour. A $15 or $20 an hour job may well be fine for young persons working their way through school. However, a majority of Michigan jobs are in occupations with a median wage of less than $40,000 a year for a 40-hour week.

To put $40,000 in context, the Michigan Association of United Ways calculates the cost of paying for basic necessities in Michigan is $61,272 for a family of two adults with one infant and one preschooler.

Then the pandemic and social distancing came to Michigan. You no longer need data to make the case that structurally the Michigan economy has too many of us working in low-wage jobs. Many without health coverage and almost none with paid leave. And because these low-wage workers are struggling to just pay the bills for necessities, most have little or no savings.

Everyday, in every community in Michigan, we are confronted with the reality of the multitude of low-wage workers who have lost their jobs and cannot pay for the basics. And we are all more aware now than ever about how much we depend on low-wage workers to get our food and prescription drugs and other daily necessities. Not to mention all the low-wage workers who are so vital in health care, child care and other caring enterprises.

That reality should now make clear to all of us that a vast majority of those struggling economically and without any safety net to deal with emergencies are hard working Michiganders. Who like us get up every day and work hard to earn a living. That the prime reason for so many struggling is not irresponsible adults coddled by a too-generous public safety net, but rather an economy, even when it is booming, has too few jobs that pay family-sustaining wages and provides health coverage and paid leave.

To their credit policymakers––on a bi-partisan basis––in both Washington and Lansing have responded to our collapsing economy by temporarily expanding unemployment and paid-leave benefits and are providing households with cash and expanded food assistance to help households pay their bills.

All of a sudden off the table are calls to continue to shrink the safety net; impose work requirements to access public benefits; and unemployment benefits that do not cover part-time and gig-economy workers.

We need that bi-partisan consensus to continue once the pandemic has passed. This is the prime economic challenge of our times: having an economy that provides family-sustaining jobs––not just any job––so that all working Michigan households can raise a family and pass on a better opportunity to their children.

We can––and should––debate how to achieve an economy that benefits all. And who should pay for the needed policies and programs. What we should not and cannot ignore is that our economy structurally is leaving too many behind.

The first step in solving this problem is to recognize that there is a structural problem that will not be fixed when the economy starts to grow again. The second step is to expand the metric of our economy’s success beyond the unemployment rate. It must also include a focus on a rising household income for all.

In order for Michigan to succeed, Michigan’s families need to succeed. As is now crystal clear, far too many of our families have not been succeeding for far too many years. If they are not succeeding, our state is not succeeding.