Three interesting recent articles on young professionals leaving Michigan for vibrant central cities, particularly Chicago. All worth checking out.

The first in the Detroit News entitled “Michigan tries to lure best, brightest back“. The article provides a good overview of why where young talent chooses to live and work matters a lot to the Michigan economy, the importance of both job/career opportunity and quality of place in choosing a place to live, the importance of central cites to retaining and attracting young talent and why mobility goes way down once you have kids.

The second a terrific Brian Dickerson column in the Free Press on the impact of legislation passed in the legislative lame duck session on the state’s ability to retain and attract talent entitled “Scaring away the grads Michigan needs to woo”. Dickerson writes:

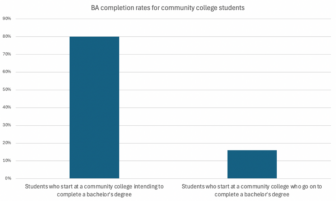

Post your job openings, he (Governor Snyder) promises, and the young graduates who worked Up North in their high school and college summers will swarm back to buy houses, start families and pay property taxes. Except they haven’t been doing that — not even in sufficient numbers to fill the high-skill jobs Michigan already has. Business Leaders for Michigan (BLM), a consortium of the state’s largest employers, warns that the supply of workers with two- and four-year degrees could fall a million short of the number needed to meet existing employers’ needs by 2025. That’s right — a million fewer college graduates than Michigan needs to fill the jobs Snyder expects to create. Dwindling government support for higher education in Michigan is a major contributor to the shortfall. “At a time when we need to grow our number of college-educated workers, Michigan’s policy on higher education discourages enrollment by making it too costly for many to attend college,” J. Patrick Doyle, President & CEO of Domino’s Pizza, told fellow CEOs at a BLM summit on higher education last May. Doyle and his peers have urged Snyder to reverse spending priorities in Michigan, which lavishes 76% more taxpayer dollars on prisons than it spends on public universities. Yet even many of those who manage to obtain degrees here quickly take them elsewhere — especially to states that haven’t muddled their messages of opportunity with official hostility to reproductive rights, same-sex marriage, immigrants and organized labor. (Emphasis added)

The third in Slate by Edward McClelland, who grew up in Michigan and now lives in Chicago, is much more pointed and quite pessimistic about Michigan’s future. Its entitled Right-to-work bill: Michigan just gives up. An anti-union bill is the wrong response to a brain drain, and ensures the state will only create low-paying jobs. McClelland writes:

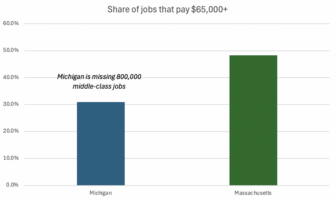

Fifty percent of Michigan State students now leave the state immediately after graduation. That ratio doubled in the 2000s, which is known in Michigan as “The Lost Decade.” In those 10 years, Michigan dropped from 30th to 35th in the percentage of college graduates, and from 18th to 37th in per capita income. (Michigan was also the only state to lose population in the last census.) The university system’s main function is giving Michigan’s brightest students a credential to get the hell off that jobless peninsula. … What does this have to do with the right-to-work law? Michigan has lost so many educated workers that the state’s leadership seems to feel it has no choice but to become a low-wage haven. … The kind of place that attracts chicken processors, not software engineers. Unable to adjust to the 21st century, Michigan is going back to the 19th. … Now, Michigan has decided to become the kind of state that Michiganders’ grandparents escaped. When it does, even more of their grandchildren will make the trek along their own Wolverine Highway, to Chicago, to New York or to Silicon Valley.Welcome to Michissippi. (Emphasis added.)

We don’t share McClelland’s pessimism. We do believe that Michigan can be a place where mobile talent wants to live and work. And if we become a talent magnet that we can become a high prosperity state again. A place with a broad middle class. But we do agree we are not going to get there––either a talent magnet or a high prosperity state––if our policies are designed to compete in the low wage, old economy. And the kind of unwelcoming policies Dickerson writes about.

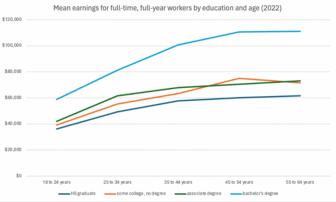

Creating a Michigan with a broad middle class can only happen if the focus of policy makers is on competing in the growing high wage knowledge-based sectors of the economy. That requires a laser focus on preparing, retaining and attracting talent as economic growth priority #1. Specifically:

- Building a culture aligned with (rather than resisting) the realities of a flattening world. We need to place far higher value on learning, an entrepreneurial spirit, and being welcoming to all.

- Ensuring the long-term success of a vibrant and agile higher education system. This means increasing public investments in higher education. Our higher education institutions—particularly the major research institutions—are the most important assets we have to develop the concentration of talent needed in a knowledge-based economy.

- Creating places where talent—particularly mobile young talent—wants to live. This means expanded public investments in quality of place, with an emphasis on vibrant central-city neighborhoods.

- Transforming teaching and learning so that it is aligned with the realities of a flattening world. Which requires an emphasis on insuring that every child attends a quality school.

- Developing new public and, most important, private sector leadership that has moved beyond a desire to recreate the old economy as well as the old fights.