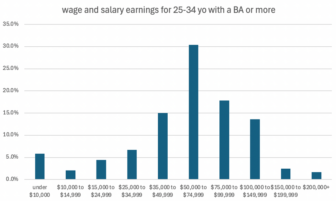

We at Michigan Future Inc. have not been shy about sharing ample research that demonstrates the ![]() correlation between degree attainment and economic stability. It’s no coincidence that Michigan ranks 32nd for both college degree attainment and per capita income. But recent research suggests that lacking a college degree may not only threaten one’s bottom line, but could risk one’s life.

correlation between degree attainment and economic stability. It’s no coincidence that Michigan ranks 32nd for both college degree attainment and per capita income. But recent research suggests that lacking a college degree may not only threaten one’s bottom line, but could risk one’s life.

Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton blame so-called “deaths of despair”- suicides, drug overdoses and alcohol-related health challenges – for a spike in midlife mortality rates among white men and women who don’t have a college degree. Meanwhile, the rates for these deaths are falling for whites who hold a college degree. For example, the rate of 50- to 54-year-old men who are college graduates is 243 per 100,000 compared to 867 per 100,000 for men who don’t hold a degree.

The researchers theorize that the elimination of jobs for men who don’t have college degrees due to automation and globalization have led to weakened social ties and more depression. As a result, problems such as substance abuse and risky behaviors have exploded.

In a recent Chronicle of Higher Education article, authors Sarah Brown and Karin Fischer take a fascinating look at the connection between health disparities and low educational attainment in the “Bootheel” region of Missouri, where poorly-educated whites are feeling the brunt of both economic deprivation and rampant health challenges. While some assume that the health disparities that separate poor whites in this battered region from their better educated neighbors are based in economics, the authors found there is more at stake.

“Better-educated people live in less-polluted areas, trust more in science, and don’t as frequently engage in risky behaviors. Have a college degree and you’re more likely to wear a seat belt and change the batteries in your smoke alarm.”

In other words, the critical thinking skills that are sharpened by a college education may help college graduates better synthesize information about the consequences of poor health choices. In addition to the “deaths of despair” examined by Case and Deaton, poorly educated people are more likely to succumb to chronic diseases. For example, Brown and Fisher cite a study that found that middle aged adults who didn’t finish high school were twice as likely to have a heart attack than those with a college degree.

For many years, higher education has been acknowledged as the most reliable engine of social mobility. However, Michigan’s leaders have defunded higher education, placing the burden for college tuition on students and their families, a move that has made college less affordable for those who need it most.

That’s why in Michigan Future Inc.’s first-ever policy agenda, we recommend three policy levers to raise household income for Michigan citizens: boosting education from birth through college; creating dynamic communities that are attractive to talented workers and creating shared prosperity for those who will find themselves left behind by workplaces that are increasingly reliant on machines.

We strongly believe that increasing the number of four-year degree holders in Michigan is the most effective strategy to boost household income, but we are equally convinced that there needs to be a coherent strategy to offer meaningful state assistance to those who have been left behind by an increasingly knowledge-based economy. The very lives of Michigan citizens may be at stake.