Metro Minneapolis-St. Paul has long been one of the nation’s most prosperous metropolitan areas with a rich mix of businesses and one of the best-educated work forces in the country.

In 2012, metro Minneapolis had per capita income of $50,260, the 27th highest of all metro areas in the United States, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Metro Detroit ranked 111th with per capita income of $42,261. Metro Grand Rapids had per capita income of $37,264 and ranked 211th.

Metro Minneapolis also had the lowest unemployment rate of any large metro area in the country in May with a jobless rate of 4 percent.

Metro Detroit was tied with Providence, Rhode Island and Riverside, California for having the highest unemployment rate at 8 percent. Metro Grand Rapids’ jobless rate in May was 5.4 percent.

Underpinning the Twin Cities’ prosperity is a decades-long commitment to regionalism, an idea that metro Detroit and many other communities have struggled to accept.

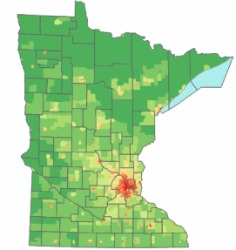

Local governments in metro Minneapolis share a portion of their tax revenues to promote more even economic development and level the tax burden throughout the seven-county region.

And the regional planning agency in the Twin Cities metro area, called the Metropolitan Council, also operates the public transit and wastewater treatment system.

Tax-base sharing in metro Minneapolis is known as the Fiscal Disparities program and was established in 1971. It shifts tens of millions of dollars among 240 local governments and school districts, and dozens of other tax authorities in the metro area.

Under Fiscal Disparities, 40 percent of the growth in the commercial and industry tax base in the metro area goes into a shared pool. Communities with a smaller per capita property value compared to the metro average get a larger distribution, while communities with a larger per capita property value get a smaller distribution.

In 2013, $390 million in tax base, or 37 percent of the commercial and industrial tax base was shared.

Not everyone has been happy with Fiscal Disparities. Some wealthy suburban communities have complained that it takes millions of dollars from their budgets and subsidizes poorer communities that don’t account for how they use the money.

But a 2012 study of the program for the Minnesota Department of Revenue concluded that donor communities weren’t especially harmed by the loss of tax base. The 234-page report did not recommend changes in the program.

Another crucial element in regionalism in metro Minneapolis is the Metropolitan Council, a regional planning agency similar to the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments in Detroit.

The Metropolitan Council was founded in 1976 and is governed by a policy board whose 17 members are appointed by the governor. Unlike SEMCOG, those members cannot be local government officials.

And also unlike SEMCOG, the Metropolitan Council has operational responsibility for the region’s mass transit and wastewater treatment systems. It claims its wastewater treatment rates are 40 percent lower than peer regions.

The Metropolitan Council collects a portion of the state’s motor vehicle sales tax and a metro-wide property tax to fund its operations.

Forty percent of this year’s $887.8 million budget comes from the state and federal government. The rest comes from the property tax, transit fares and wastewater treatment charges.

The Metropolitan Council says it works to foster prosperity in metro Minneapolis by promoting “a healthy environment, clean water, convenient transit options, parks for recreation and exercise, and housing options.”

Its efforts appear to be succeeding. The Twin Cities, as well as the rest of the state, regularly rank high in national “quality of life” surveys.

Metro Minneapolis ranked fifth highest among the 52 largest metro areas in this year’s Gallup Well-Being study, based on more than 500,000 telephone interviews. Metro Detroit ranked 50th.

Read the latest report from Michigan Future here.