Editor’s Note: This article appeared in the September/October 2023 issue of the Michigan Planner. The Michigan Planner magazine is delivered six times per year to members of the Michigan Association of Planning, the Michigan Chapter of the American Planning Association. The Michigan Association of Planning exists to promote quality community planning through education, information and advocacy, statewide. More information available at www.planningmi.org.

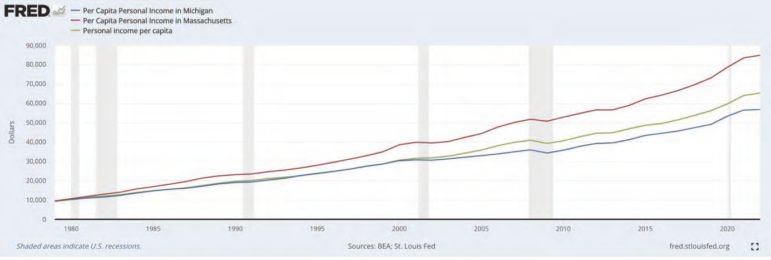

In the 20th Century, Michigan was a high-prosperity state. Now we are a 21st Century low-prosperity state. Ranking 38th in per capita income, 13% below the national average in 2022, see line graph below. This is the lowest Michigan has been in per capita income compared to the nation ever. The core reason for this unprecedented collapse in economic well-being is that the Michigan economy has too many low-wage jobs. A state that once attracted people from across the planet to get high-paid jobs is now a state with median wages nearly 10% below the nation’s median wage. Six in ten Michigan jobs pay less than what is required for a family of three to be middle class.

That decline is due in large part to choices Michigan has made: focused on trying to make an old economy work again. It’s the old economy that made Michigan prosperous in the past, but it no longer exists, no matter how much you try to revive it. That old economy vision and strategy, if continued, will insure that Michigan remains a low-prosperity state with a high proportion of households struggling to pay for necessities.

Michigan can return to high-prosperity – a place where all who work hard can pay the bills and save for their retirement and the kids’ education. But that requires a willingness to make big changes in state policy. A small course correction to our economic and education agendas will not be sufficient – transformational change in both is required if we are to restore Michigan to high-prosperity.

Over three decades of rigorous data analysis shows that in today’s economy, talent attracts capital and quality of place attracts talent. The most consistent predictor of a state’s economic success is the share of its adults – particularly young adults – with a four-year degree. Where young talent goes, high-growth, high-wage, knowledge-based enterprises follow, expand, and are created. Because talent is the asset that matters most to high-wage employers and is in the shortest supply, the new path to prosperity is concentrated talent – and the key to concentrating talent is vibrant communities.

Transformative placemaking should be the driving force for successful economic

development. The key to growing high-wage jobs is attracting college-educated members of Generation Z. Michigan cannot get prosperous again until and unless we become a talent magnet for these young people. Focusing on traditional economic development priorities while failing to concentrate young talent in the state will ensure Michigan remains a permanently low-prosperity state.

Because young talent is the most mobile, economic development policies should be squarely focused on creating the kinds of places where highly-educated young people want to live and work. Attracting and retaining highly-educated young people is the state’s primary economic imperative – both keeping the young talent that grows up here and attracting young talent from any place on the planet.

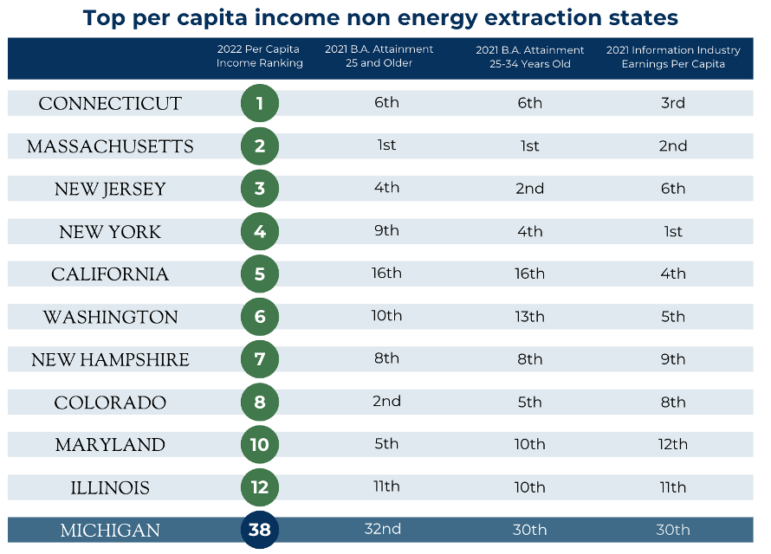

The data show that highly-educated young people are increasingly concentrating in regions that are transit rich with vibrant central cities. Every high-prosperity state that is not energy extraction driven has at least one metropolitan area anchored by a vibrant central city where

both the region and the city have a high proportion of young adults with a B.A. or more.

Michigan’s current economic development playbook focused largely on business attraction is endangering the long-term health of our economy and the economic well-being of households because it does not incorporate the value of place. To recreate a Michigan with lots of good paying career opportunities – we need to create regions that are:

- Welcoming to all no matter where one is born, one’s sexual orientation, race, religion or ethnic background.

- Provide extensive transit — particularly rail transit –– as the 21st Century infrastructure that matters most to retaining and attracting young talent

- Offer talent magnet neighborhoods in our central cities and small towns. These neighborhoods vary in many ways, but all share common characteristics: they are dense, walkable, high- amenity neighborhoods, with parks, outdoor recreation, retail, and public arts woven into residents’ daily lives. And they offer plentiful alternatives to driving.

For Michigan’s population to get younger and more talented, significant public investment is required. Those public investments must be designed explicitly to provide the infrastructure and amenities that Generation Z demands. This is not a set of recommendations that can be done

on the cheap or by tinkering at the edges. The states that have won in the transition to the high-wage knowledge economy are those that have invested deeply and sustainably in the infrastructure and amenities of their central cities.

In reviewing the Table of Top 10 Non Energy Extraction States, one might come to the conclusion that Michigan’s fate is a forgone conclusion given its geography. But that is not the case. Minnesota ranks #15 to Michigan’s #38. Minnesota is the Great Lakes model for public investment led economic development.

At its core, the Minnesota playbook for economic and demographic success has been higher taxes––with state taxes $2,145 higher per capita than Michigan in 2021. These taxes paid for public investments by offering good schools from birth through college and creating places where people want to live by offering high quality basic services, infrastructure and amenities.

The state has successfully competed for talent. Minnesota has not lost a congressional seat for six decades. By contrast, Michigan has lost at least one seat in Congress each of the last five decades. Each decade since 1960, Minnesota has had 8 congressional seats. In 1960, Michigan had 19 congressional seats, today it has 13.

Minnesota is also a national leader in retaining and attracting recent college graduates. Minnesota is one of only nine “brain-gain” states with 8% more recent college graduate residents compared to those who graduated from its college and universities. By contrast, Michigan is a “brain-drain” state with 14% fewer college graduate residents compared to those who graduated from its college and universities.

Minnesota is also a high-prosperity state. In 1979, Minnesota’s per capita income was 1% above the national average, Michigan was 3% above. In 2022 Minnesota’s per capita income is 4% above the nation’s; Michigan’s is 13% below. Michigan could have chosen Minnesota’s playbook. But to date, leaders have not. Michigan can only reverse four decades of population and economic well-being decline by changing its strategy. It must make retaining and attracting talent economic development priority on — as Minnesota has done.