Adapted from Michigan Future, Inc. President Lou Glazer’s Growing Michigan Together Council presentation on November 2, 2023.

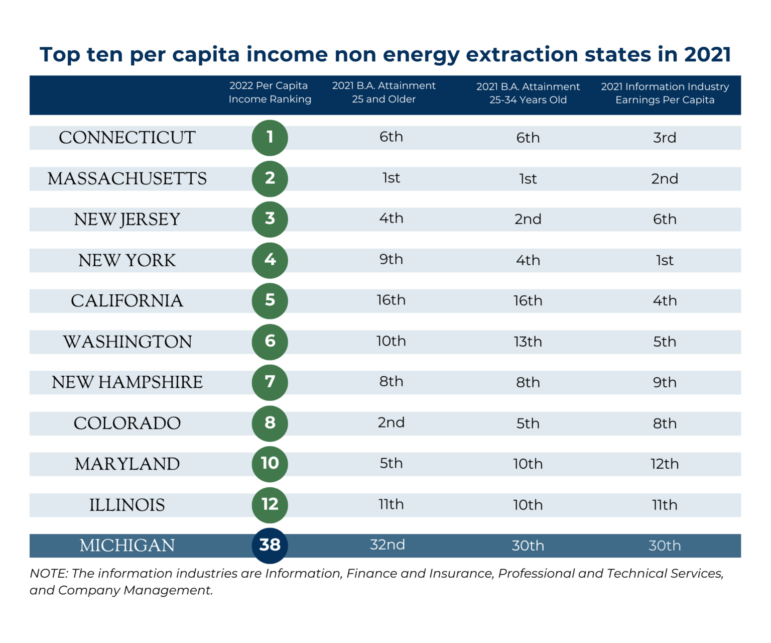

Michigan was a 20th Century high-prosperity state. Now we are a 21st Century low-prosperity state. Ranking 39th in per capita income, 13 percent below the national average in 2022. This is the lowest Michigan has been compared to the nation ever.

This is not a partisan issue. This decline has happened under both Republican and Democratic administrations and control of the legislature.

The core reason for this unprecedented collapse in economic well-being is that the Michigan economy has too many low-wage jobs. A state that once attracted people from across the planet to get high-paid jobs is now a state with median wages nearly ten percent below the nation’s. Six in ten Michigan jobs pay less than what is required for a family of three to be middle class.

What we have been doing to increase the economic well-being of Michiganders has not worked. A small course correction will not be sufficient––transformational change in our approach to the economy and education is required if we are to achieve an economy that as it grows benefits all.

In today’s economy, the reality is talent attracts capital and quality of place attracts talent. The most consistent predictor of a state’s economic success is the share of its adults––particularly young adults––with a B.A. or more.

Where young talent goes, high-growth, high-wage, knowledge-based enterprises follow, expand, and are created. Because talent is the asset that matters most to high-wage employers and is in the shortest supply, the new path to prosperity is concentrated talent.

Transformative placemaking should be the driving force for successful economic development. The key to growing high-wage jobs in Michigan is attracting college-educated members of Generation Z after they finish their education. Michigan cannot get prosperous again until and unless we become a talent magnet for these young people. Focusing on traditional economic development priorities while failing to concentrate young talent in the state will ensure Michigan remains a permanently low-prosperity state.

Because young talent is the most mobile, economic development policies should be squarely focused on creating the kinds of places where highly-educated young people want to live and work. Attracting and retaining highly-educated young people is the state’s primary economic imperative––both keeping the young talent that grows up here and attracting young talent from any place on the planet.

For the first time we have data on where 26-year-olds lived when they were 16 by regions that include every county in America. The data is for those who turned 26 between 2010 and 2018.

About 30 percent of all 26-year-olds moved regions from where they lived as 16-year-olds. About 40 percent of those who grew up in top quintile households––which unfortunately is a good surrogate for those with a B.A. or more––moved regions. The bigger the metro, the more who stay.

The higher the parents’ income, the more who leave. Michigan regions look basically the same as the nation in terms of the percent of young adults who did not move. What distinguishes us big time is the small proportion of those who moved in.

Each of the top eight have more top quintile movers than the entire state of Michigan. Of the one million Black young adult movers Atlanta is by far first. Houston is second. Detroit is 35th. Grand Rapids does not make the top 100. We may think of Detroit as America’s leading Black city. Black young adults don’t.

So, what can we learn from this data that can help inform our efforts to attract young talent to Michigan?

The basic story is movers are moving to big metros with vibrant central cities which by and large are high-cost places with high amenities. This is true for all movers irrespective of education attainment.

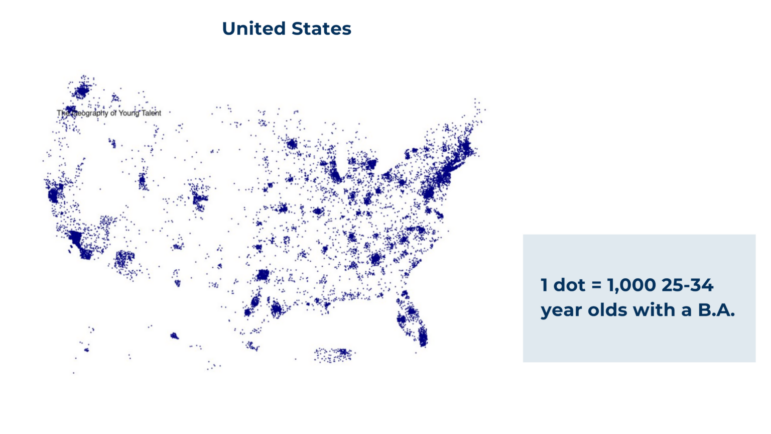

Young people, and highly educated young people in particular, are flocking to major metropolitan areas anchored by vibrant central cities. These young people are seeking out central cities that feature dense, walkable, activity-rich neighborhoods.

The places that they are moving to are not low tax places and they are most definitely not low housing cost places. Nor are they places with high standardized tests scores or places with affordable, abundant childcare. They are not particularly warm weather places, nor are they particularly southern. And they are in both red and blue states.

So, what are the core characteristics of the places where young adults movers are concentrating? Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg got it exactly right when he wrote in a 2012 Financial Times op-ed:

“For cities to have sustained success, they must compete for the grand prize: intellectual capital and talent. I have long believed that talent attracts capital far more effectively and consistently than capital attracts talent. Economists may not say it this way but the truth of the matter is: being cool counts. When people can find inspiration in a community that also offers great parks, safe streets and extensive mass transit, they vote with their feet.”

Tami Door, then-CEO of the Downtown Denver Partnership, and the architect of the city’s leading-edge placemaking economic development strategy, also got it right when she wrote in 2012: “Mountains and oceans have become secondary to downtown amenities.” In 2005, just after passage of a 98-mile regional light rail transit plan, Denver with the mountains was the home of 45,000 young professionals. Today with great transit and one of America’s most vibrant central cities Denver has 110,00 young professionals. Great cities trump great natural resources.

Despite conventional wisdom to the contrary, young professionals post pandemic are not fleeing big cities. The places where young adult movers were moving to prior to the pandemic are the same places where young professionals are concentrated post pandemic. In 2021, New York City was the home of 773,000 25–34-year-olds with a B.A. or more. Chicago is 3rd nationally and a Great Lakes best with 307,000 young professionals. All ten of the top ten cities for top quartile movers are the home in 2021 of at least 100,000 young professionals. By comparison, the city of Detroit has 20,000, the city of Grand Rapids 22,000 and Ann Arbor 18,000.

Michigan’s current economic development playbook focused largely on business attraction is endangering the long-term health of our economy and the economic well-being of households because it does not incorporate the value of place.

To create a Michigan with lots of good-paying career opportunities we need to strengthen and create more vibrant neighborhoods in our cities that can attract and retain young talent.

For Michigan to become a high-prosperity state once again, we need great schools along with great cities.

More specifically, we need to increase the share of young Michiganders who pursue and complete a four-year degree.

Since most of the young adults who live in Michigan will be raised here, for the foreseeable future they will largely determine Michigan’s talent concentrations. Nearly three quarters of Michigan payroll jobs that pay $80,000 or more are in professional and managerial occupations that require a four-year degree. So, the more Michigan students who have a B.A. or more the better able the state will be to grow high-wage jobs.

Maybe more importantly, increasing the share of young non-affluent Michiganders who pursue and complete a four-year degree is––by far––the most powerful lever for expanding economic opportunity. Increasing four-year degree completion rates for non-affluent students is now an economic imperative.

We are on the opposite track at the moment. The education that is provided affluent students is, by and large, designed and executed differently than it is for non-affluent kids. One system delivers a broad college prep–dare we say liberal arts–education designed to prepare students for a successful forty-year career; the other is designed to deliver an increasingly narrow education built around developing discipline, teaching to what is on the test and narrowly preparing non-affluent children for a first job.

As you would expect, these two systems get the results they are designed to get.

The Federal Reserve found that among individuals aged 22-29, 72 percent of those with at least one parent holding a bachelor’s degree also possess a B.A. In contrast, only 35 percent of those in the same age group, whose parents have some college education but neither has a bachelor’s degree, have attained a B.A. Further, only 19 percent of individuals aged 22-29, whose both parents have a high school degree or less, have achieved a B.A.

All of this adds up to the reality that there are two high-impact levers available to state policymakers to reverse Michigan’s decades-long economic well-being decline:

- First, create transit-rich, vibrant central cities that are competitive with America’s young adult talent magnet regions.

- Second, create schooling from birth through college that substantially increases Michigan student’s four-year degree attainment.

If you do not concentrate college-educated Generation Z here, and do not substantially increase four-year degree attainment of Michigan students – Michigan will continue to get poorer compared to the rest of the nation.

Getting younger and better educated requires making bold public investments in place and education––the drivers of today’s economy. The alternative is clear: Michigan will continue to get older and poorer.