A decade ago in a column for Dome we made the case that Indiana’s low tax economic strategy was a failure and would continue to fail going forward. We wrote:

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy on Monday is hosting an event with Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels as the featured speaker. This is a continuation of a decades-long tradition of inviting Indiana governors — mainly Republican — to tell us the policies they have pursued to grow the Indiana economy, so we can learn from them what to do.

One problem: Indiana is today, and has been for decades, the poorest and least educated Great Lakes state. That’s right. Even after Michigan’s awful so-called lost decade, Indiana is poorer than we are.

What Indiana is best at among the Great Lakes states is adherence to the low tax/small government policies advocated by conservatives as the magic elixir to grow the economy. In the 2011 state rankings by the well-respected conservative Tax Foundation, Indiana is the highest ranked Great Lakes state on both overall state business climate (10th) and corporate tax index (21st). The latter is the lever the Snyder Administration has argued is the most important to growing the Michigan economy.

But for the vast majority of Michiganders who care about whether they have a job and a good income to raise a family, Indiana doesn’t look so good. Indiana’s per capita income, proportion of households with incomes of $75,000 or more, poverty rate and proportion of adults with a four-year college degree are all the worst among Great Lakes states.

Fast forward a decade an important new report from Michael Hicks, director of The Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University and professor of economics in the Miller College of Business, chronicles the failure of Indiana’s low tax economic development strategy over the past decade. Hicks writes:

The ten-year span of 2009-2019 saw the longest economic expansion in U.S. history. Indiana began this recovery period behind the nation in almost every important economic metric and then fell farther behind throughout the decade.

Indiana’s weak recovery saw the state perform much worse than the nation in measures of job creation, GDP growth, population growth, productivity growth, and personal income growth. The causal factor in this decline is the state’s relatively declining levels of educational attainment.

Hicks attributes this much worse than the nation economic performance to the state’s low tax economic strategy in an economy where college attainment––specifically four-year degree attainment–-is the defining characteristic of prosperous states. Hicks writes:

… Since 2010, in real terms, state and local governments have spent an additional $5 billion on business tax incentives, but added only $17 million to the budgets of colleges and universities. The intent of this funding shift was to ensure Indiana remained a low-tax state. Proponents believed the supply-side effects of this environment would attract new businesses and boost employment opportunities, wages, labor productivity, and overall economic growth. This approach enjoys widespread political support, but there is little to no empirical support.

By employing data on GDP growth and the Tax Foundation’s data on total state tax burdens, we see the elusive nature of this relationship. From these most basic data there is no statistically or economically meaningful relationship between tax rates and growth.

In the wake of these policies, the Indiana economy grew slowly and the job growth that occurred was clustered at the low end of the skill and income distribution. The productivity of Hoosier workers (average product of labor) lagged significantly, and the incomes declined relative to the nation as a whole. Business growth plummeted and measures of economic wellbeing across many domains languished. In short, the low-tax, policies pursued from 2010 through 2019 failed to produce broad economic growth.

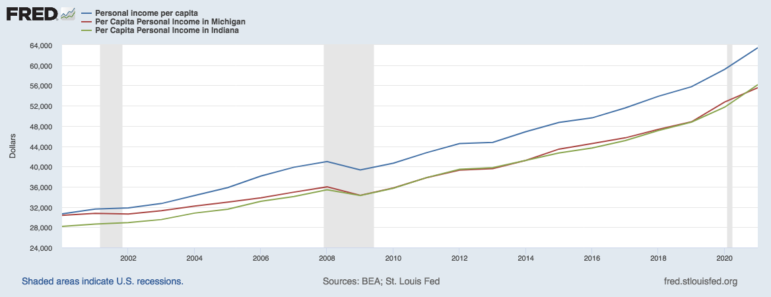

Hicks analysis is important to those of us in Michigan because Michigan has for decades been following the same low tax economic playbook as Indiana with the same poor economic results. One can make a strong case for the past two decades Michigan’s decline compared to the nation is worse than Indiana’s. The chart below shows per capita income from 2000-2021 for the U.S., Michigan and Indiana.

In 2000 Michigan’s per capita income was one percent below the nation’s. Indiana was eight percent below. By 2009––the depths of the Great Recession––both Michigan and Indiana had per capita income 13 percent below the nation’s. In 2021 Michigan per capita income is 12 percent below the nation’s. Indiana’s is 11 percent below.

Both states are now structurally low prosperity. Michigan ranks 34th, Indiana 33rd in per capita income. This despite Michigan ranking 12th in the Tax Foundation’s 2022 State Business Tax Climate Index. Indiana ranked 9th. As Hicks says “From these most basic data there is no statistically or economically meaningful relationship between tax rates and growth.”

In the 2011 column we identified talent as the asset that mattered most to state and regional prosperity. We wrote:

Our basic conclusion is that what most distinguishes successful areas — such as Minnesota, which has all of those attributes — from Michigan is their concentrations of talent, where talent is defined as a combination of knowledge, creativity and entrepreneurship. Quite simply, in a flattening world where work can increasingly be done anyplace by anybody, the places with the greatest concentrations of talent win.

States and regions without concentrations of talent will have great difficulty retaining or attracting knowledge-based enterprises, and they are less likely to be the place where new knowledge-based enterprises are created. The knowledge-based economy is now the path to prosperity Michigan must pursue.

Pursuing that path means preparing, retaining and attracting talent is economic development priority #1. If we do everything else well that we call economic development and we don’t get younger and better educated, Michigan will continue to get poorer compared to the nation.

Michigan has lagged in its support of the assets necessary to develop the knowledge-based economy at the needed scale. Building that economy is going to take a long time and require fundamental change. But the data show it is the only reliable path to regaining high prosperity.

There are no quick fixes. The Michigan economy is going to continue to lag the nation for the foreseeable future. But there is a path back to high prosperity. The framework for action is:• Build a culture aligned with (rather than resisting) the realities of a flattening world. We need to place far higher value on learning, an entrepreneurial spirit and being welcoming to all.

• Creating places where talent — particularly mobile young talent — wants to live. This means expanded public investments in quality of place with an emphasis on vibrant central city neighborhoods.

• Ensuring the long-term success of a vibrant and agile higher-education system. This requires a renewed commitment to public investments in higher education — particularly the major research universities.

• Transforming teaching and learning so that they are aligned with the realities of a flattening world.

• Developing new private and public sector leadership that has moved beyond both a desire to recreate the old economy as well as the old fights. Michigan needs leadership that is clearly focused, at both the state and regional level, on preparing, retaining and attracting talent.The world has changed fundamentally. The choice we face is this: do we do what is required to build the assets needed to compete in a knowledge-based economy or do we accept being a low-prosperity state?

Michigan decided to stay the low tax course. And got the anticipated results: becoming structurally a low-prosperity state. A decade later the choice the state faces is the same: do we make preparing, retaining and attracting talent economic development priority #1 or do we accept continuing to be a low-prosperity state?