At Michigan Future, there is a core assumption that underlies our approach to changing our state for the better, and today I want to reflect on how this assumption is relevant to our work in education. That assumption is the belief—based on countless observations—that what we measure matters. When you (whether a person, an organization, a community, a state) define a goal, you automatically begin to delineate what is inside and what is outside of the scope of your pursuit of that goal. And if its measurement is defined somewhat short of the true goal (maybe because the true goal is hard to measure, or you’ve confused one outcome with the real goal), the achievement will also fall short. In education, I think our system is designed around the wrong measures. If we realign around measures of what truly matters, we’ll see how desperately the whole system needs to be redesigned.

Measure What Matters

A quick illustration: early in our work with Michigan Future Schools, we as an organization assumed that college success (degree achievement) would naturally derive from college access. If a young person could enter college, we hoped she would succeed there. We know now that it’s far from true and the implications about how to better prepare her reach well back into that young person’s childhood. How you prepare her to succeed is a far vaster task than how you prepare her to get admitted. We weren’t the only organization to make this mistake, and fortunately, lots of organizations around the country have shifted their thinking and we’ve been learning alongside them. Because our goal was always college achievement, and our measure was always college persistence and graduation, we were able to learn why access wasn’t enough. If we’d defined our job as access only, we would never have known how far off the mark we were of achieving college degrees for students, and how differently they needed to be prepared.

So how we measure our success will guide the learning we undertake as we pursue a thorny goal. If we don’t measure something, we won’t focus on it. And if it’s hard to measure, it’s likely to end up outside of the work, even if it’s actually critically important.

In education, it’s become our belief that for too long, we’ve been narrowing the aperture through which we look at Michigan’s children and what education is supposed to be for them. By placing immense weight on standardized test results for the evaluation of our teachers, schools, and students, we shrink the importance of helping our children to foster absolutely critical skills through school. When success in adult life is actually about these critical skills—being able to work with others, communicate effectively, problem-solve, and adapt to new situations—we are widening the achievement gap if we focus our teaching of poor children on content that can be measured on tests, while affluent children have all sorts of opportunities to develop these more complex skills.

In their book Timeless Learning: How Imagination, Observation, and Zero-Based Thinking Change Schools, Ira Socol, Pam Moran, and Chad Ratliff helped my brain crystallize something I’ve witnessed in our education system. They dive into the history of education in America and find that our education system was designed to filter, not to uplift. (We also discussed this in my What Now? interview with Ira and Pam.)

Filtering, Not Uplifiting

Filtering means creating barriers to find out who can overcome them, so that an ever-smaller group of people emerge at each level with the qualifications to run the show.

If you understand this, you’ll start to see it everywhere. This filtering was baked into the origins of our system, when our economy needed standardized laborers with a few standout leaders. And while the system also saw marvelous inventiveness and evolution in the mid-1900s, that inventiveness was often doled out on segregated lines. We did not achieve uplift across the entire system. Then, over the past 30 years, the system has regressed to work, overall, much like it did originally.

There’s an expression that every system is perfectly designed to get the results it’s getting.

In our system today:

- Almost four in ten Michigan families are struggling to afford basic necessities.

- Standardized tests results can be largely correlated with the income of families being tested.

- Even though the state has equalized its per pupil spending, affluent districts still spend thousands more dollars per student than poorer districts are able to do.

- At some high schools, college attendance and graduation is the norm. This is also largely correlated with parent income. (Play around with the Mi School Data to check the college progression data for the high schools you know to be wealthier or poorer, and be sure to pay attention to four-year degree attainment, which can vary tremendously.)

- At some colleges, graduation is expected. At others, fewer than 20 percent of kids get a degree.

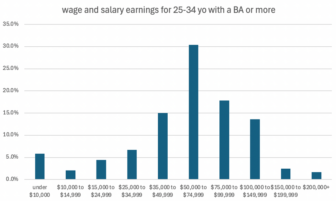

- Middle-class and above jobs are predominantly the domain of people with four-year college degrees.

- Every aspect of this has a racial opportunity gap.

This is all despite the best efforts of the wonderful teachers and administrators that populate the system and who are driven by personal missions to support the personal development of the students they encounter.

In other words, our system keeps producing inequitable results because it is designed to get inequitable results. A single driven teacher cannot counter this system for more than a handful of kids.

We can’t be a prosperous state if opportunities for good jobs, good wages, good health, and stable lives are limited to people whose parents were successful before them.

So, even if the people in the system are good, the system has to change from top to bottom–starting by measuring what really matters.

After a number of years, I’m preparing to step away from my work at Michigan Future at the end of this month. I am offering a series of reflections on education in Michigan from my years of work understanding what the future, and the present, will demand of our children. While there have been many others, my most critical learning opportunities have been: our relationships with the school leaders that were a part of Michigan Future Schools; planning, with a series of remarkable educators, the Outsmarting the Robots event, where we tried to model the learning experiences we should be offering to kids; and each of the leaders, educators, and researchers I interviewed during the pandemic for What Now?–our video series on education.