Terrific Nicholas Kristof New York times column on Denmark. The article’s subtitle says it all: Danes haven’t built a “socialist” country. Just one that works.

Similar to Finland, Denmark is a capitalist economy with widely shared prosperity. Each offers a model for how to realize the reformed capitalism that, as we have explored in previous posts, American capitalists like Ray Dalio, Nick Hanauer, Tom Wilson and Mark Benioff have called for.

Kristof describes the results of Denmark’s style of capitalism this way:

… while Americans on both left and right often think of Scandinavia as quasi-socialist, Scandinavians flinch at that characterization. They see themselves as simply pursuing market economies, just with higher taxes and greater social benefits than the United States.

Danes pay an extra 19 cents of every dollar in taxes, compared with Americans, but for that they get free health care, free education from kindergarten through college, subsidized high-quality preschool, a very strong social safety net and very low levels of poverty, homelessness, crime and inequality. On average, Danes live two years longer than Americans.

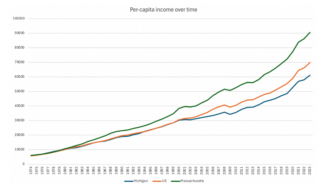

… Danes earn about the same after-tax income as Americans, even though they work on average 22 percent fewer hours; on the other hand, money doesn’t go as far in Denmark because prices average 18 percent higher. My own rough guess is that the top quarter of earners live better in America, but that the bottom three-quarters live better in Denmark.

The eye catching fact of Kristof’s article is that “starting pay for the humblest burger-flipper at McDonald’s in Denmark is about $22 an hour once various pay supplements are included.” You read that right $22 an hour for fast-food restaurant workers, plus generous benefits.

Kristof explains Danish capitalism this way:

Americans assume that Danish wages must be high because of regulations, but Denmark has no national minimum wage, and it would be perfectly legal for a construction company or a corner pizzeria to hire workers at $5 an hour. Yet that doesn’t happen. The typical bottom market wage seems to be about $15 — about twice the federal minimum wage in the United States, a country with a roughly similar standard of living. Why is that?

One reason is Denmark’s strong unions. More than 80 percent of Danish employees work under collective bargaining contracts, although strikes are rare. There is also “sectoral bargaining,” in which contracts are negotiated across an entire business sector — so in Denmark, McDonald’s and Burger King pay exactly the same — something that Joe Biden suggests the United States consider as well.

Yet there’s another, more important reason for high wages in Denmark.

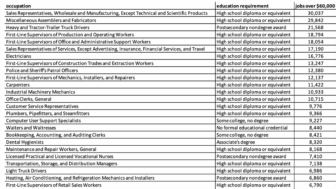

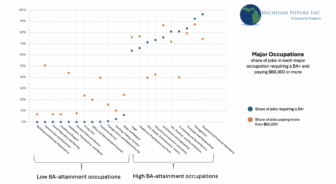

“Workers are more productive” in Denmark, Lawrence Katz, a labor economist at Harvard, noted bluntly. “They have had access to more and higher-quality human capital investment opportunities starting at birth.”

Think of it this way. Workers at McDonald’s outlets all over the world tend to be at the lower end of the labor force, say the 20th percentile. But Danish workers at the 20th percentile are high school graduates who are literate and numerate.

In contrast, after half a century of underinvestment in the United States, many 20th-percentile American workers haven’t graduated from high school, can’t read well, aren’t very numerate, struggle with drugs or alcohol, or have impairments that reduce productivity.

Increasingly, I came to see that emulating a Danish-style system of high wages wasn’t just about lifting the minimum wage but, even more, about investing in children.

The lesson of Denmark is that the most impactful levers that allow you to have a capitalist economy that benefits all––which we all say we want––are a strong safety net, strong unions, and investment in children. Yes these levers require higher taxes. But boy do you get a lot for those higher taxes.

Pre-pandemic the U.S. and Michigan had been going in the opposite direction for decades. Weaker safety net, weaker unions, underinvestment in children from birth through college. The result: a Michigan economy where four in ten households in our strong pre-pandemic economy were struggling to pay for basic necessities. Sure seems like it is time for change.