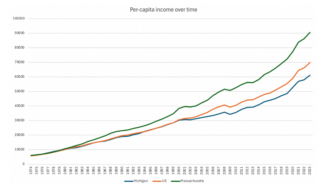

This is our third recent post on reforming capitalism so that it works for all. The first featured the writings of hedge fund billionaire Ray Dalio on the reality for forty years growth in the American economy has not benefited the bottom 60 percent and a call for action to change that reality. The second featured the ideas of venture capitalist Nick Hanauer to reform capitalism through policies that share security with all largely through employer mandates on wages and benefits.

This post features the ideas of the pro-market Niskanen Center. If Hanauer represents someone from the left thinking about how to have a capitalism that works for all, the Niskanen Center is a place thinking about the same challenge from the political right.

New Times columnist David Brooks described the Niskanen Center this way:

The Niskanen Center began operations in 2015, started by a group of libertarians who broke off from the Cato Institute. … But Niskanen thinkers like Ed Dolan, Samuel Hammond and Will Wilkinson made a simple and empirically verifiable observation. The nations that have the freest markets also generally have the most generous welfare states. The two are not in opposition. In the real world they go together.

… Last week, Niskanen released a comprehensive report called, “The Center Can Hold: Public Policy for an Age of Extremes,” written by Brink Lindsey, Steven Teles, Wilkinson and Hammond. The report is a manifesto for a new centrism based on what the authors call a “free-market welfare state” model.

They want government to protect citizens against the disruptions of global capitalism: “Without strong income supports that put a floor beneath displaced workers and systems that smooth the transition to new employment, political actors and the public tend to turn against the process of creative destruction itself.”

At the same time, they want an open, dynamic society. They want to reduce restrictive zoning and land use regulations that favor the rich and entrenched. They see immigration as crucial to America’s long-term prosperity. They want charter schools and wider choice, but within strong government structures to ensure quality. (It turns out that bad charter schools continue to attract students; the education market doesn’t work totally unregulated.)

The Center’s approach to economic policy that works for all is laid out in a policy essay entitled The Free-Market Welfare State. In it they write:

It is one thing to admit that the social insurance state is better for economic freedom relative to some other, abjectly worse alternative. It’s another thing entirely to reconcile the fact that social insurance states like Sweden and Denmark routinely score near the top in rankings of personal and economic freedom, even when such rankings are constructed by conservative and libertarian organizations that stack the deck against a high-tax-and-spend approach to fostering an open society. For a Hayekian this makes perfect sense: Central planning is an enemy to freedom because it does damage to the individual’s capacity to plan for him or herself.

Social insurance, in contrast, exists to enhance an individual’s capacity to plan by imposing a degree of certainty on future states of the world. The societal value of social insurance is thus not unlike the societal value of rule-bound monetary policy, property rights, or the rule of law. In each case, the institution evolved to provide a level of social continuity—

whether in terms of stable prices, secure ownership and contract, or “regulatory certainty”— needed for more specialized and complex economic coordination.

So they like Dalio and Hanauer believe that to preserve capitalism you need a set of policies that insure that the economy is working for all. Samuel Hammond, the author of the policy essay, writes:

I argue that the contemporary rise of anti-market populism in America should be taken as an indictment of our inadequate social-insurance system, and a refutation of the prevailing “small government” view that regulation and social spending are equally corrosive to economic freedom. The universal welfare state, far from being at odds with innovation and economic freedom, may end up being their ultimate guarantor.

As an example of the kind of social insurance policy the Center supports take a look at their analysis supporting the child tax credit proposed by Democratic United States Senators Sherrod Brown and Michael Bennet. The proposal, called the American Family Act, would enact a huge increase in federal support over the current child tax credit and would provide income monthly rather than annually when one files their taxes. As the Center writes: “Under the American Family Act, households would be eligible for: $300 per month ($3,600 per year) for each child under the age of 6; and $250 per month ($3,000 per year) for each child under the age of 17. The benefit would begin phasing-out at a rate of 15 or 18 percent (depending on the household mix of young and older children) for individual and joint filers with incomes above $130,000 and $180,000 respectively. The maximum credit amounts are also indexed to inflation.”

The Center’s preference, as represented by the American Family Act, is for cash benefits and for those benefits to be universal––not just for those below a certain income.

What Dalio, Hanauer, and the Niskanen Center (and Michigan Future) have in common is a belief in capitalism as the system that best creates a growing and innovative economy and a belief that that is not enough. That what is desired is an economy that also benefits all. A standard that the American economy has failed to meet for four decades.

And each explicitly rejects the notion that small government/low tax places have the best economies.

Each has different approaches to policy to achieve those ends. That is what the debate should be all about. What we need first and foremost is a bipartisan agreement that the mission of economic policy is an economy that benefits all. Where all really means all. Then let the debate begin over how to achieve that mission.