Really interesting research from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on low-wage workers moving up to better-paying jobs. (You can find the research here and a ![]() summary article on the research here.) The report’s core findings:

summary article on the research here.) The report’s core findings:

Using data covering the expansion following the Great Recession (2011-17) and focusing on short-term labor market transitions, we find that around 70 percent of low-wage workers stayed in the same job, 11 percent exited the labor force, 7 percent became unemployed, and 6 percent switched to a different low-wage job. Troublingly, just slightly more than 5 percent of low-wage workers found a better job within a 12-month period.

So if you are in a low-wage job you are far more likely (18 percent) next year to not be working than you are to move from a bottom quartile job to one in the second through fourth quartiles (5 percent). Not exactly the story we like to tell ourselves about low-wage work as the first rung on a job ladder that will take many to better-paying jobs as their career progresses.

The report uses the term low-wage worker for bottom-quartile occupations, but they calculate occupation status based on more than wages. They also measure employer paid health care benefits, whether the job is full time or not and the occupation’s prestige. Bottom-quartile occupations: ” … pay an average wage of $13 per hour. They deviate by an average of seven hours from a 40-hour work week and provide benefits for less than half of those who hold them.”

Other key takeaways from the research:

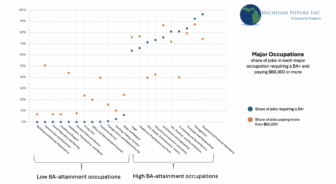

- The more education and the younger you are the more likely you are to move up to a higher-quartile occupation

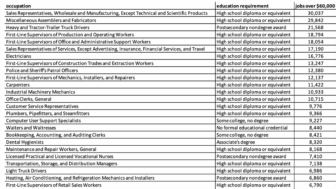

- The occupations bottom-quartile workers most move up to are truck driver, office assistance and sales.

- Very few move up to a better-paying job in manufacturing

- People with low-wage jobs in the health care and social assistance industry are likely to keep the same occupation or transition into a different low-wage job—healthcare (and social assistance) workers are less likely to move into better jobs.

- The job types with better long-term prospects to move up are those that involve people skills, including communication, presentation, and organization.

Richard Florida, one of the report’s authors, concludes that:

Even with the unemployment rate at less than 4 percent, more than 65 million Americans—almost half of the entire workforce—toil in low-paying jobs in fields such as food service, retail, and personal and health services. The only real solution to America’s jobs problem is to make these currently low-paying and precarious service jobs into better, higher-paying jobs.

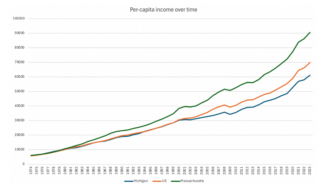

The combination of too many low-quality jobs and the reality that very few low-quality job holders move up even in a strong economy makes the case that we need to explicitly make shared prosperity an economic priority. We detail the need for a shared prosperity policy agenda and lay out what that agenda should include in our Sharing prosperity with those not participating in the high-wage knowledge-based economy report. In it we write:

How do we help those not capturing the benefits of globalization and technological change –– in Michigan’s case, the majority of workers –– earn enough to pay the bills, save for retirement and their kids’ education, and pass on a better opportunity to the next generation? The answers largely need to come through public policy. Market forces alone, almost certainly, will not turn low-skill, low-wage jobs into family-supporting work. The only way we can do that is through a commitment to shared prosperity.

Along with access to education, opportunity also means supporting all Michiganders in navigating the barriers that stand between them and a full-time, family-supporting job. A range of roadblocks ranging from limited knowledge of job openings; to lack of housing, transportation and childcare; to lack of work-ready or job-specific skills; to physical or mental health issues; to a history of addiction or incarceration, often block the path of those seeking work. Further, people facing barriers almost always struggle with more than one. What’s needed is a comprehensive approach to mitigating these obstacles, such that we can get more Michiganders into full-time work.

Finally, opportunity means that available jobs need to offer sufficient hours and wages to, at minimum, keep workers out of poverty, and ideally offer a spot in a broad middle-class. Many jobs available to Michigan workers fail to provide income security. Over 40 percent of jobs in Michigan pay less than $15 per hour. In addition to getting individuals into work, we need to ensure that work offers financial security. Augmenting wages and benefits through some combination of employer mandates and/or a strengthened safety net.

The most impactful employer mandates levers we identified include boosting the minimum wage; improving collective bargaining rights; paid family and medical leave; and insuring stability for hourly workers. The most impactful strengthened safety net levers we identified include an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit and protecting and expanding Medicaid and CHIP.