Read this and let it sink in for a minute:

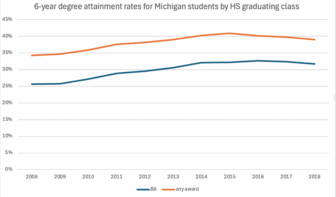

A man with only a high school diploma is twice as likely to be out of work as a man who has a four-year college degree. And, of the 9.3 million men between the ages of 25 and 50 who weren’t working last year, 1.7 million had a bachelor’s degree or higher, 2.3 million had some college or an associate’s degree, and 5.3 million had nothing beyond a high school degree.

A post from Brookings entitled “Why are so many American men not working?” highlights the work of David Wessel, who found last year (“Men Not at Work“) that one in seven men in prime working age aren’t working––they are unemployed right now or have stopped looking for work altogether. Wessel suggests these are the primary causes:

- educational attainment, whose effects are described above;

- increasing incarceration rates, which lead to lower employability;

- the use of pain medication (40 percent of non-working men are taking pain medication every day!);

- more men are on disability, and once men go on disability they rarely come off; and

- low wages, which aren’t an enticement to work.

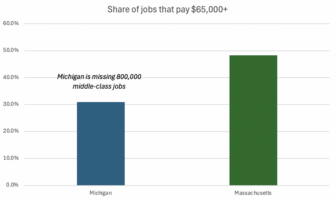

While Wessel offers some policy prescriptions, to me there are two primary upshots. First, we need to prepare future men (i.e., current students in our schools) to face a dynamic economy with skills that will allow them to succeed. They need to be ready for college, if they choose to attend, and “career readiness” should mean that students are creative, can think critically, and have other skills that allow them to be adaptable in this ever-changing economy.

Second, the causes of declining employment for men are really, really complicated, but are certainly education- and skill-related. The job market is changing so that new and higher skill levels are needed. Our workforce development programs don’t have a great track record. We over-incarcerate, especially African-American men. And as unemployment stretches into long-term unemployment, it’s increasingly difficult to land a job.

No one policy solution is likely to remedy all of these factors, but our support systems for the unemployed need to have the flexibility to address multiple barriers at once. On top of that, a focus on equipping people with higher skills must be at the center.