According to a 2016 Great Lakes Economic Consulting report entitled Michigan’s Great Disinvestment, 11 Michigan cities, one township, one county, and five school districts are in official states of financial emergency. Though cities around the country have struggled with municipal finance, especially in the wake of the Great Recession, the problem has been particularly acute in Michigan. This is at least partly due to constitutional amendments that limit the rate at which property taxes can increase (to the rate of inflation), and the rate at which cities can increase millages. These factors combine so city revenues can drop precipitously—say, for instance, during a recession and foreclosure crisis—but cannot rebound as quickly when values start to pick up again. Michigan further ties the hands of cities to independently raise revenue by levying additional taxes, as, for instance, Philadelphia just did with a soda tax.

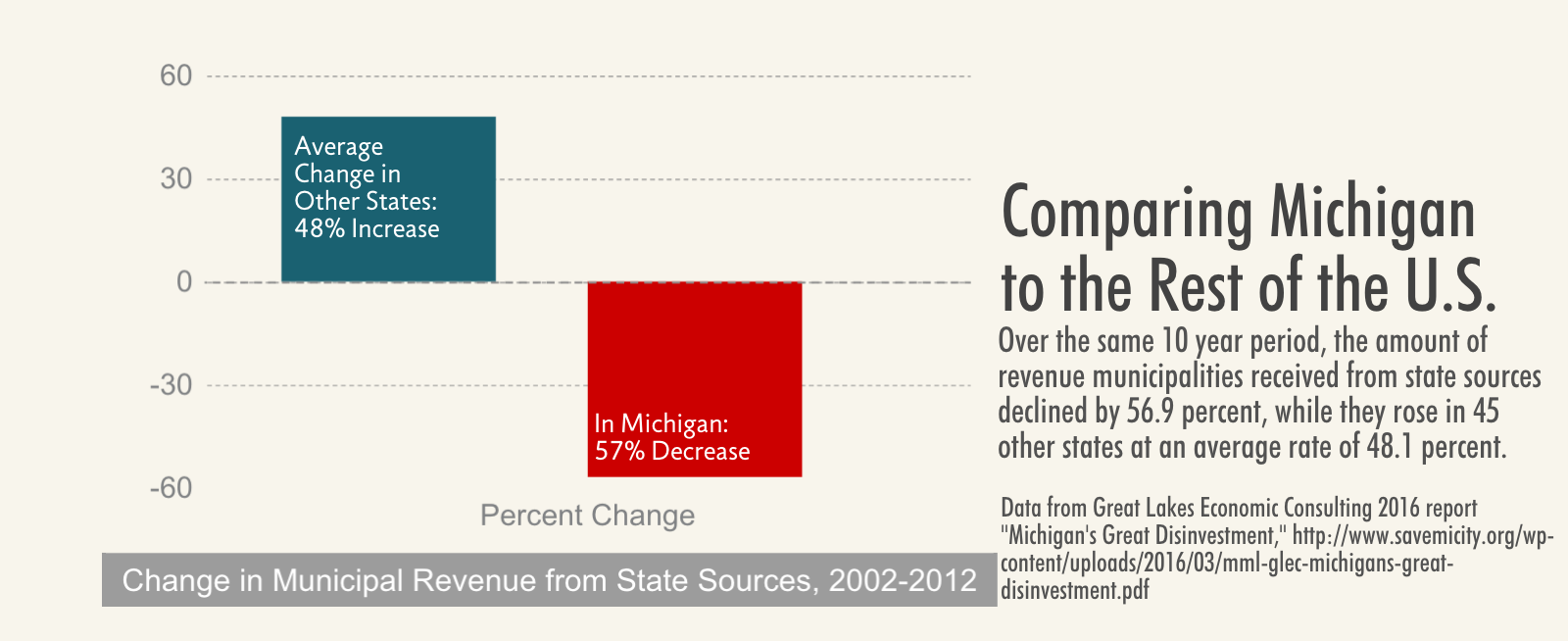

But the real gut-punch here has been a set of shell games at the state wherein revenues that statutorily, but not constitutionally, are “supposed” to be allocated by the legislature to cities, villages, and townships (this is known as revenue sharing) are being diverted to cover state budgets. Since 1998, the state has largely failed to fully fund its revenue sharing commitment to local municipalities, causing larger and larger budget challenges for the cities trying to fund police and fire departments, trash pickup, and streetlights. Michigan’s Great Disinvestment estimates that between 1998 and 2016, the gap between the actual funding that Michigan’s local governments received and what would have been the fully funded levels of revenue sharing is $5.538 billion. Between 2002 and 2012, while 45 states have increased municipal revenue from state sources—by an average of 48.2 percent—Michigan led the nation in revenue sharing cuts. #Winning!

(Occasionally you will hear that corruption and waste are the big problems here. Whether intentionally or not, people who say that are offering a smoke screen that obfuscates the reality of state funding declines.)

A recent survey of local officials by CLOSUP (the Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy at University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School for Public Policy) found that 64 percent of Michigan’s local officials say that, “the state’s system of funding local government is broken and needs significant reform.” Further, only 40 percent expect that the current funding system will allow them to continue to provide the jurisdiction’s current level of services. In other words, 60 percent of cities, villages, townships and counties expect to have issues maintaining services in the near future (if they don’t already). And the issue isn’t limited to large cities, a particular region of the state, or to the political party of the respondents. This survey saw across-the-board recognition that we are failing to invest in our local communities in the ways that they need.

Why does this matter? Beyond the obvious (I, for one, appreciate having my trash picked up, roads plowed, and streetlights lit), these budget shortfalls make it impossible for our cities to become the places that attract and retain people who have choices about where they live. If this isn’t your first time on the Michigan Future blog (and even if it is), you probably know that we’re in the midst of a demographic sea change, where college-educated talent—the workforce that employers are looking for—are moving to cities at unprecedented rates. They are seeking walkable downtowns, transit options, and an amenity-rich urban lifestyle. How can we expect our cities to meet these needs while they are struggling to—quite literally—keep the lights on?