Thomas Sugrue is the author of the must-read “The Origins of the Urban Crisis”, a history of the deindustrialization of Detroit. He was a keynote speaker at the last Detroit Regional Chamber’s Detroit Policy Conference.

Prior to the speech he did an interview with John Gallagher of the Detroit Free Press which was entitled: “Sugrue: Trickle-down urbanism won’t work in Detroit”. At about the same time City Lab published an article entitled “What Millennials Want—And Why Cities Are Right to Pay Them So Much Attention”. Both are worth checking out.

What I want to deal with in this post is why Michigan Future is an advocate for the approach laid out in the Atlantic Cities article, not the one taken by Sugrue. We frequently encounter that our emphasis on talent––those with four year degrees or more––is elitist.

First lets deal with the trickle down charge. Trickle down normally is used to disparage policies designed for the 1% and corporate America. A critique we agree with. The evidence is pretty strong that simply making things better for the 1% and corporate America does little to create either jobs or income for American households.

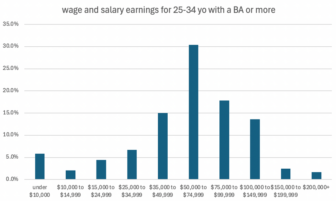

Young professionals are hardly the 1%. They, by and large, like most Americans are struggling to find good paying jobs and good places to live. Nor do they, by and large, have a political agenda that is asking for special treatment. If they have an agenda at all it is communities with the basic services and amenities they value and maybe some help with student loans. Which they are struggling with because public policy has dramatically reduced public support for higher education which was available to their parents.

Sugrue says in the Free Press interview: “But the future of a city, if it’s going to be successful, the future of Detroit is going to be improving the everyday quality of life for residents who are living a long way from downtown and a long way from Midtown, who probably aren’t ever going to spend much time listening to techno or sipping lattes.”

Characterizing young professionals as people who listen to techno and sip lattes is both insulting and inaccurate. But the more important point is that his vision of a successful city––a city anchored by working class families raising children––is long gone. (Interestingly many of the young professionals in Detroit, who Sugrue disparages, are big advocates for policies and/or have jobs focused on improving the quality of life of the poor and working class households in the city.)

The reality is, not largely because of city policy, but rather consumer demand, the working class households Sugrue wants cities to focus on when they––from all races––get decent paying jobs, in large proportions, leave the city for the suburbs. Not just in Detroit, but across the country. One can make a far better case, when it comes to place-making policy for decades Michigan and the country have had a policy of providing working class families with the neighborhoods and quality of life they want. In low density, car dependent suburbs. That policy orientation is still predominant in Michigan and metro Detroit.

The reality also is, as Gallagher points out in the interview with Sugrue, that “we’ve (Detroit) been trying to work on those poorer neighborhoods for at least 50 years now through a variety of programs.” That has been the priority agenda for the city for decades.

The chief reason Detroit and other big cities should focus on young professionals––and to some degree college educated empty nesters––is they want to live in cities, not the suburbs. (Alan Ehrenhardt details changing demand for city living in his terrific book “The Great Inversion”.) One can make a strong case that Detroit policy for decades has stood in the way of young professionals moving to the city. By not providing quality basic services to any resident and not providing the mixed use, high density, walkable, transit rich neighborhoods they are looking for.

The Atlantic Cities article is about that changing consumer demand. Citing recent polls by the Rockefeller Foundation with Transportation for America and the American Planning Association. Atlantic Cities writes: “Two public opinion polls came out in the last month suggesting the kinds of places Millennials like. Spoiler alert: it’s Boston, New York, San Francisco, and Chicago, as well as communities such as—I’m inclined to say once again, of course—Boulder and Austin. The key characteristics seem to be walkability, good schools and parks, and the availability of multiple transportation options.”

What is elitist or trickle down about cities responding to changing consumer demand? What is elitist or trickle down about creating cities and neighborhoods with “walkability, good schools and parks, and the availability of multiple transportation options”? What is wrong with Detroit competing with Boston, New York, San Francisco, and Chicago for these residents? Creating a place attractive to those who want to live in central cities is the only way Detroit is going to repopulate. And repopulating is the key to Detroit being a viable city long term.