A year ago I read about someone who suggested that for those working on city revitalization, Brooklyn was a far more realistic model than Manhattan. The notion being that the assets and scale of Manhattan are not replicable. It seemed like good advice then and even more so now.

At the time I read that advice, Brooklyn was just starting its redevelopment. No guarantee that it was going to be a success story. As is clear from a recent New York Times article entitled Brooklyn’s New Gentrification Frontiers today there is no question that it is a success.

Today’s success was built on decades of pessimism. Brooklyn not that long ago was a national symbol of irreversible urban decline. As the Times writes Brooklyn’s revitalization “pushes deeper into neighborhoods that for some New Yorkers still evoke images of burned-out buildings, riots and poverty.”

Once the revitalization began, the legions of doubters maintained that it would be limited to a few neighborhoods closest to Manhattan and the water front. Think again! As the Times reports: “The median real estate price for Boerum Hill ($675,000), Carroll Gardens ($677,500) and Cobble Hill ($750,000), once viewed as out-of-the-way destinations for renters and homeowners unable to afford Manhattan, now rivals those in the northern reaches of the Upper East and West Sides and parts of Lower Manhattan, according to Streeteasy.com. … Housing prices in neighborhoods deeper inside Brooklyn are even competing with or surpassing real estate in solidly middle-class areas of Westchester County, Long Island and northern New Jersey, according to Trulia.com.”

What are the lessons we should learn from Brooklyn? The Times article demonstrates:

- People want to live in cities. The widespread belief in Michigan and across most of America that no one but the poor want to live in cities is simply out of date.

- Cities that work are first and foremost residential neighborhoods –– places where people want to live. So much so that they are willing to pay higher housing costs for high density, mixed use, walkable neighborhoods. The kind of neighborhoods only found in cities.

- Public safety and rail transit matter. People won’t live in neighborhoods that are not safe, and increasingly want rail transit to connect them to jobs and entertainment.

- Predictions that urban revitalization is consigned to a very small portion of cities –– basically downtown and near downtown neighborhoods –– should be ignored. The evidence is that there is demand for housing in urban neighborhoods beyond downtown.

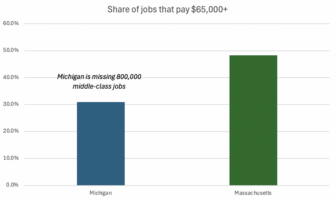

Michigan’s challenge is to learn both that central cities are an essential component of prosperous states and what needs to be done to make them a reality here.